SNAPSHOT

Created at: 2018-12-03 20:36

AOP ID and Title:

Graphical Representation

Status

| Author status | OECD status | OECD project | SAAOP status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open for comment. Do not cite | EAGMST Under Review | 1.7 | Included in OECD Work Plan |

Abstract

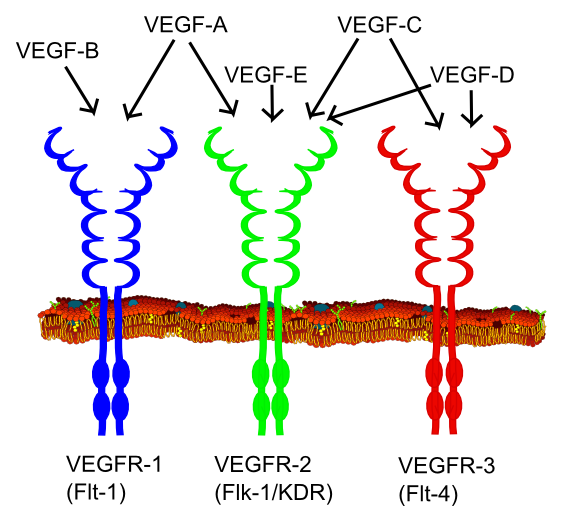

Interference with endogenous developmental processes that are regulated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), through sustained exogenous activation, causes molecular, structural, and functional cardiac abnormalities in avian, mammalian and piscine embryos; this cardiotoxicity ultimately leads to severe edema and embryo death in birds and fish and some strains of rat (Carney et al. 2006; Huuskonen et al. 1994; Kopf and Walker 2009). There have been numerous proposed mechanisms of action for this toxicity profile, many of which include the dysregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as a key event, as it is essential for normal vasculogenesis and therefore cardiogenesis (Ivnitski-Steele and Walker 2005). This AOP describes the indirect suppression of VEGF expression through the sequestration of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) by AHR. ARNT is common dimerization partner for both AHR and hypoxia inducible factor alpha (HIF-1α), which stimulates angiogenesis through the transcriptional regulation of VEGF (Ivnitski-Steele and Walker 2005). There is considerable cross talk between these two signaling pathways (AHR and HIF-1α), leading to the hypothesis that AHR activation leads to sustained AHR/ARNT dimerization and reduced HIF-1α/ARNT dimerization, preventing the adequate transcription of essential angiogenic factors, such as VEGF. The suppression of VEGF thereby reduces cardiomyocyte and endothelial cell proliferation, altering cardiovascular morphology and reducing cardiac output, which ultimately leads to congestive heart failure and death (Lanham et al. 2014).

The biological plausibility of this AOP is strong, and there is significant evidence in the literature to support it; however, there exist some contradictory data regarding the effect of AHR on VEGF, which seem highly dependent on tissue type and life stage. There are also multiple targets of AHR activation, such as the COX-2 signaling pathway, that could potentially interact. These contradictions and alternate pathways are discussed below. The quantitative understanding of individual key even relationships (KERs) in this AOP is weak; however, there is a strong correlation between the molecular initiating event (MIE: AHR activation) and adverse outcome (AO: embryolethality), and a quantitative relationship is described for birds.

Background

In 1957, millions of broiler chickens died due to a mysterious chick edema disease characterized by pericardial, subcutaneous and peritoneal edema (SCHMITTLE et al. 1958). This disease was later ascribed to the ingestion of feed contaminated with halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons (HAHs), including 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) (Higginbotham et al. 1968; Metcalfe 1972). It has since become evident that TCDD is a prototypical agonist of the AHR: a transcription factor that modulates the expression of a vast array of genes involved in endogenous development and physiological responses to exogenous chemicals (Denison et al. 2011). A general study in the 1980’s found that mothers exposed to herbicides during pregnancy had a 2.8-fold increase in risk of having a baby with congenital cardiovascular malformations (Loffredo et al. 2001). Epidemiological studies have correlated long-term TCDD exposure with ischemic heart disease (Bertazzi et al. 1998; Flesch-Janys et al. 1995); interestingly, and consistent with this AOP, sectioned and stained heart samples from patients with this disease lack epicardial cells (Di et al. 2010). Mammalian studies have confirmed that in utero exposure to TCDD increases susceptibility to cardiovascular dysfunction in adulthood (Aragon et al. 2008; Thackaberry et al. 2005b). The developing heart is highly dependent on oxygen saturation levels; somewhat counterintuitively, a state of hypoxia (relative to adult oxygen tension) drives normal formation and maturation. Deviation from this optimal oxygen level, either above or below normal, hinders myocardial and endothelial development, altering coronary artery connections, ventricle wall thickness and chamber formation (Patterson and Zhang 2010; Wikenheiser et al. 2009). Interestingly, AHR activation (by TCDD), inhibition, and knockdown significantly inhibited the formation of contractile cardiomyocyte nodes during spontaneous differentiation of embryonic stem cells into cardiomyocytes (in vitro) (Wang et al. 2013), indicating that AHR also has an optimal window of expression for normal cardiogenesis. TCDD significantly reduces the degree of myocardial hypoxia that normally occurs during myocyte proliferation and ventricular wall thickening in the developing embryo (Ivnitski-Steele et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2001). This reduction in hypoxia is associated with reduced expression of both HIF-1and the VEGF splice variant, VEGF166 mRNA, which is one of the primary VEGF variants required to mediate coronary vascularization (Ivnitski-Steele et al. 2004). Therefore, it is biologically plausible that sustained AHR activation sequesters ARNT from HIF-1α impairing hypoxia stimulated coronary angiogenesis.

Summary of the AOP

Events

Molecular Initiating Events (MIE), Key Events (KE), Adverse Outcomes (AO)

| Sequence | Type | Event ID | Title | Short name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MIE | 18 | Activation, AhR | Activation, AhR |

| 2 | KE | 944 | dimerization, AHR/ARNT | dimerization, AHR/ARNT |

| 3 | KE | 945 | reduced dimerization, ARNT/HIF1-alpha | reduced dimerization, ARNT/HIF1-alpha |

| 4 | KE | 948 | reduced production, VEGF | reduced production, VEGF |

| 5 | KE | 110 | Impairment, Endothelial network | Impairment, Endothelial network |

| 6 | KE | 317 | Altered, Cardiovascular development/function | Altered, Cardiovascular development/function |

| 7 | AO | 947 | Increase, Early Life Stage Mortality | Increase, Early Life Stage Mortality |

Key Event Relationships

| Upstream Event | Relationship Type | Downstream Event | Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activation, AhR | adjacent | dimerization, AHR/ARNT | High | Moderate |

| dimerization, AHR/ARNT | adjacent | reduced dimerization, ARNT/HIF1-alpha | Moderate | Low |

| reduced dimerization, ARNT/HIF1-alpha | adjacent | reduced production, VEGF | Moderate | Moderate |

| reduced production, VEGF | adjacent | Impairment, Endothelial network | High | Low |

| Impairment, Endothelial network | adjacent | Altered, Cardiovascular development/function | Moderate | Low |

| Altered, Cardiovascular development/function | adjacent | Increase, Early Life Stage Mortality | High | Low |

| Activation, AhR | non-adjacent | Increase, Early Life Stage Mortality | High | Moderate |

Stressors

| Name | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Polychlorinated biphenyl | High |

| Polychlorinated dibenzodioxins | High |

| Polychlorinated dibenzofurans | High |

Polychlorinated biphenyl

Certain polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) congeners are potent AHR agonists, and lead to dioxin-like cardiotoxicity in birds (Carro et al. 2013a; Carro et al. 2013b; Brunstrom, B. 1989; Rifkind et al. 1984) and fish (Clark et al. 2010; Olufsen and Arukwe 2011; Grimes et al. 2008). Furthermore, PCB contamination in wild avian species has been correlated with altered heart size and morphology (DeWitt et al. 2006; Henshel and Sparks 2006).

Of the dioxin-like PCBs, non-ortho congeners are the most toxicologically active, while mono-ortho PCBs are generally less potent (McFarland and Clarke 1989; Safe 1994). Chlorine substitution at ortho positions increases the energetic costs of assuming the coplanar conformation required for binding to the AHR (McFarland and Clarke 1989). Thus, a smaller proportion of mono-ortho PCB molecules are able to bind to the AHR and elicit toxic effects, resulting in reduced potency of these congeners. Other PCB congeners, such as di-ortho substituted PCBs, are very weak AHR agonists and do not likely contribute to dioxin-like effects (Safe 1994).

References

Carro, T., Dean, K., and Ottinger, M. A. (2013a). Effects of an environmentally relevant polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) mixture on embryonic survival and cardiac development in the domestic chicken. Environ.Toxicol.Chem.

Carro, T., Taneyhill, L. A., and Ottinger, M. A. (2013b). The effects of an environmentally relevant 58 congener polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) mixture on cardiac development in the chick embryo. Environ.Toxicol.Chem.

Brunstrom, B. (1989). Toxicity of coplanar polychlorinated biphenyls in avian embryos. Chemosphere 19, 765-768.

Rifkind, A. B., Hattori, Y., Levi, R., Hughes, M. J., Quilley, C., and Alonso, D. R. (1984). The chick embryo as a model for PCB and dioxin toxicity: Evidence of cardiotoxicity and increased prostaglandin synthesis. In Biological Mechanisms of Dioxin Action (A. Poland and R. D. Kimbrough, Eds.), pp. 255–266. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

Clark, B.W.; Matson, C.W.; Jung, D.; Di Giulio, R.T. 2010. AHR2 mediates cardiac teratogenesis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and PCB-126 in Atlantic killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus). Aquat. Toxicol. 99, 232-240.

Olufsen, M. and Arukwe, A. (2011) Developmental effects related to angiogenesis and osteogenic differentiation in Salmon larvae continuously exposed to dioxin-like 3,3’,4,4’-tetrachlorobiphenyl (congener 77). Aquatic Toxicology 105: 669– 680

A.C. Grimes, K.N. Erwin, H.A. Stadt, G.L. Hunter, H.A. Gefroh, H.J. Tsai, M.L. Kirby (2008) PCB126 exposure disrupts zebrafish ventricular and branchial but not early neural crest development Toxicol. Sci., 106, pp. 193-205

DeWitt, J. C., Millsap, D. S., Yeager, R. L., Heise, S. S., Sparks, D. W., and Henshel, D. S. (2006). External heart deformities in passerine birds exposed to environmental mixtures of polychlorinated biphenyls during development. Environ.Toxicol.Chem. 25, 541-551.

Henshel, D. and Sparks, D.W. (2006) Site Specific PCB-Correlated Interspecies Differences in Organ Somatic Indices. Ecotoxicology, 1: 9-18

Safe, S. (1994). Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): Environmental impact, biochemical and toxic responses, and implications for risk assessment. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 24, 87-149.

McFarland, V. A., and Clarke, J. U. (1989). Environmental occurrence, abundance, and potential toxicity of polychlorinated biphenyl congeners: Considerations for a congener-specific analysis. Environ.Health Perspect. 81, 225-239.

Polychlorinated dibenzodioxins

- Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs), which includes 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), represent some of the most potent AHR ligands (Denison et al. 2011).

- When screened for their ability to induce aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase activity, an indirect measurement of AHR activation, dioxins with chlorine atoms at a minimum of three out of the four lateral ring positions, and with at least one non-chlorinated ring position are the most active (Poland and Glover 1973).

- Until recently, TCDD was considered to be the most potent dioxin-like compound (DLC) (van den Berg et al. 1998); however, recent reports indicate that 2,3,4,7,8-pentachlorodibenzofuran (PeCDF) is more potent than TCDD in some species of birds (Cohen-Barnhouse et al. 2011; Farmahin et al. 2013; Hervé et al. 2010)

- TCDD induced cardiotoxicity in developing chick (Heid et al. 2001; Walker et al. 1997; Walker and Catron 2000) and zebrafish (Antkiewicz et al. 2005; Belair et al. 2001; Henry et al. 1997; Plavicki et al. 2013) embryos.

- Kopf and Walker (2009) provide a concise overview of DLC induced heart defects in fish, birds and mammals.

References:

Denison, M. S., Soshilov, A. A., He, G., DeGroot, D. E., and Zhao, B. (2011). Exactly the same but different: promiscuity and diversity in the molecular mechanisms of action of the aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor. Toxicol. Sci. 124(1), 1-22.

Poland, A., and Glover, E. (1973). Studies on the mechanism of toxicity of the chlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins. Environ. Health Perspect. 5, 245-251.

van den Berg, M., Birnbaum, L. S., Bosveld, A. T., Brunstrom, B., Cook, P., Feeley, M., Giesy, J. P., Hanberg, A., Hasegawa, R., Kennedy, S. W., Kubiak, T. J., Larsen, J. C., Van Leeuwen, F. X. R., Liem, A. K. D., Nolt, C., Peterson, R. E., Poellinger, L., Safe, S., Schrenk, D., Tillitt, D. E., Tysklind, M., Younes, M., Wærn, F., and Zacharewski, T. R. (1998). Toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) for PCBs, PCDDs, PCDFs for humans and wildlife. Environ. Health Perspect. 106(12), 775-792.

Cohen-Barnhouse, A. M., Zwiernik, M. J., Link, J. E., Fitzgerald, S. D., Kennedy, S. W., Hervé, J. C., Giesy, J. P., Wiseman, S. B., Yang, Y., Jones, P. D., Wan, Y., Collins, B., Newsted, J. L., Kay, D. P., and Bursian, S. J. (2011b). Sensitivity of Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica), Common pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), and White Leghorn chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) embryos to in ovo exposure to TCDD, PeCDF, and TCDF. Toxicol. Sci. 119(1), 93-103.

Farmahin, R., Manning, G. E., Crump, D., Wu, D., Mundy, L. J., Jones, S. P., Hahn, M. E., Karchner, S. I., Giesy, J. P., Bursian, S. J., Zwiernik, M. J., Fredricks, T. B., and Kennedy, S. W. (2013). Amino acid sequence of the ligand binding domain of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor 1 (AHR1) predicts sensitivity of wild birds to effects of dioxin-like compounds. Toxicol. Sci. 131(1), 139-152.

Hervé, J. C., Crump, D. L., McLaren, K. K., Giesy, J. P., Zwiernik, M. J., Bursian, S. J., and Kennedy, S. W. (2010). 2,3,4,7,8-pentachlorodibenzofuran is a more potent cytochrome P4501A inducer than 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in herring gull hepatocyte cultures. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 29(9), 2088-2095.

Heid, S. E., Walker, M. K., and Swanson, H. I. (2001). Correlation of cardiotoxicity mediated by halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons to aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation. Toxicol. Sci 61(1), 187-196.

Walker, M. K., and Catron, T. F. (2000). Characterization of cardiotoxicity induced by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and related chemicals during early chick embryo development. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 167(3), 210-221.

Walker, M. K., Pollenz, R. S., and Smith, S. M. (1997). Expression of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and AhR nuclear translocator during chick cardiogenesis is consistent with 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced heart defects. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 143(2), 407-419.

Antkiewicz, D. S., Burns, C. G., Carney, S. A., Peterson, R. E., and Heideman, W. (2005). Heart malformation is an early response to TCDD in embryonic zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 84(2), 368-377.

Belair, C. D., Peterson, R. E., and Heideman, W. (2001). Disruption of erythropoiesis by dioxin in the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 222(4), 581-594.

Henry, T. R., Spitsbergen, J. M., Hornung, M. W., Abnet, C. C., and Peterson, R. E. (1997). Early life stage toxicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 142(1), 56-68.

Plavicki, J., Hofsteen, P., Peterson, R. E., and Heideman, W. (2013). Dioxin inhibits zebrafish epicardium and proepicardium development. Toxicol. Sci. 131(2), 558-567.

Kopf, P. G., and Walker, M. K. (2009). Overview of developmental heart defects by dioxins, PCBs, and pesticides. J. Environ. Sci. Health C. Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev. 27(4), 276-285.

Polychlorinated dibenzofurans

Polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs) are potent AHR ligands (Denison et al. 2011). Recent reports indicate that 2,3,4,7,8-pentachlorodibenzofuran is more potent than TCDD, the prototypical AHR ligand, in some species of birds (Cohen-Barnhouse et al. 2011; Farmahin et al. 2013; Hervé et al. 2010). 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzofuran and 2,3,4,7,8-pentachlorodibenzofuran have been shown to induce cardiotoxicity in chicken embryos (Heid et al. 2001). Variouse PCDF congener were shown to cause early life-stage mortality in ranbow trout (Walker and Peterson 1995; Walker et al. 1997).

References:

Denison, M. S., Soshilov, A. A., He, G., DeGroot, D. E., and Zhao, B. (2011). Exactly the same but different: promiscuity and diversity in the molecular mechanisms of action of the aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor. Toxicol. Sci. 124(1), 1-22.

Cohen-Barnhouse, A. M., Zwiernik, M. J., Link, J. E., Fitzgerald, S. D., Kennedy, S. W., Hervé, J. C., Giesy, J. P., Wiseman, S. B., Yang, Y., Jones, P. D., Wan, Y., Collins, B., Newsted, J. L., Kay, D. P., and Bursian, S. J. (2011b). Sensitivity of Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica), Common pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), and White Leghorn chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) embryos to in ovo exposure to TCDD, PeCDF, and TCDF. Toxicol. Sci. 119(1), 93-103.

Farmahin, R., Manning, G. E., Crump, D., Wu, D., Mundy, L. J., Jones, S. P., Hahn, M. E., Karchner, S. I., Giesy, J. P., Bursian, S. J., Zwiernik, M. J., Fredricks, T. B., and Kennedy, S. W. (2013). Amino acid sequence of the ligand binding domain of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor 1 (AHR1) predicts sensitivity of wild birds to effects of dioxin-like compounds. Toxicol. Sci. 131(1), 139-152.

Hervé, J. C., Crump, D. L., McLaren, K. K., Giesy, J. P., Zwiernik, M. J., Bursian, S. J., and Kennedy, S. W. (2010). 2,3,4,7,8-pentachlorodibenzofuran is a more potent cytochrome P4501A inducer than 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in herring gull hepatocyte cultures. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 29(9), 2088-2095.

Walker, M.K.; Cook, P.M.; Butterworth, B.C.; Zabel, E.W. and Peterson, R.E. (1995) Potency of a Complex Mixture of Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-dioxin, Dibenzofuran, and Biphenyl Congeners Compared to 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in Causing Fish Early Life Stage Mortality. Fundamental and Applied Toxicology 30(2): 178-186.

Walker, M.K. and Peterson, R.E. (1991) Potencies of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin, dibenzofuran, and biphenyl congeners, relative to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, for producing early life stage mortality in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Aquatic Toxicology 21: 219-238.

Overall Assessment of the AOP

Domain of Applicability

Life Stage Applicability| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Embryo | High |

| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| chicken | Gallus gallus | High | NCBI |

| zebrafish | Danio rerio | High | NCBI |

| mouse | Mus musculus | Low | NCBI |

| Rattus norvegicus | Rattus norvegicus | Low | NCBI |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

| Female | High |

Life Stage Applicability, Taxonomic Applicability, Sex Applicability

Elaborate on the domains of applicability listed in the summary section above. Specifically, provide the literature supporting, or excluding, certain domains.

Life Stage Applicability: Exposure must occur early in embryo development in utero (mammals) or in ovo (birds and fish). Mammalian studies often dose between gestational days 14.5 and 17.5 as it represents a developmental window of cardiomyocyte proliferation (Kopf and Walker 2009). Cardiotoxicity has been observed in birds dosed on day zero or day 5 of incubation (Ivnitski-Steele et al. 2005; Walker et al. 1997). Zebrafish seem to have a particular sensitive window of cardio-development between 48 hours-post-fertilization (hpf) and 5 days pf, and become resistant to AHR-mediated cardiotoxicity if exposed after epicardium formation is complete (2 weeks pf) (Plavicki et al. 2013).

Taxonomic Applicability: Early embryonic exposure to AHR-agonists in mice causes cardiotoxicity that persists into adulthood, increasing susceptibility to heart disease (Thackaberry et al. 2005b) and can increased resorptions and late stage fetal death with edema in certain strains of rat (Huuskonen et al. 1994). AHR-agonists also cause cadivascular malformations in birds and fish, and the resulting reduction in cardiac output is fatal (Kopf and Walker 2009).

Therefore, this AOP is most strongly applicable to birds and fish. Although strong AHR agonists cause foetal mortality in mice and rats (Kawakami et al. 2005; Hassoun et al. 1997; Sparschu et al. 1970; Debdas Mukerjee 1998), cardiac malformation is rarely cited as a cause of death. It appears that AHR-mediated effects on cardiaovascular development in mammals more frequently lead to long-term functional deficiencies rather than foetal death.

Sex applicability: Embryonic dysfunction is equally robust in males and females, but adult abnormalities of mice exposed in utero are more prevalent in females (Carreira et al. 2015)

Essentiality of the Key Events

Molecular Initiating Event Summary, Key Event Summary

Provide an overall assessment of the essentiality for the key events in the AOP. Support calls for individual key events can be included in the molecular initiating event, key event, and adverse outcome tables above.

Molecular initiating event: AHR activation (Essentiality = Strong)

- Zebrafish AHR2 morphants (transient knock-out of function) are protected against reduced blood flow, pericardial edema, erythrocyte maturation, and common cardinal vein migration (Bello et al. 2004; Carney et al. 2004; Prasch et al. 2003; Teraoka et al. 2003)

- AHR2-/- zebrafish mutants were protected against TCDD toxicity, including pericardial edema and epicardium development (Goodale et al. 2012; Plavicki et al. 2013)

- AHR activation specifically within cardiomyocytes accounts for heart failure (cardiac malformations, loss of circulation, pericardial edema) induced by TCDD as well as non-cardiac toxicity (swim bladder inflation and craniofacial defects) in zebrafish (Lanham et al. 2014).

- AHR-null mice have impaired angiogenesis in vivo: endothelial cells failed to branch and form tube-like structures (Roman et al. 2009).

- Ischemia-induced angiogenesis was markedly enhanced in AHR-null mice compared with that in wild-type animals (Ichihara et al. 2007)

Key Event 1: AHR/ARNT dimerization (Essentiality = Strong)

- ARNT1 is essential for normal vascular and hematopoietic development (Abbott and Buckalew 2000; Kozak et al. 1997; Maltepe et al. 1997)

- zfarnt2-/- mutation is larval lethal, and the mutants have enlarged heart ventricles and an increased incidence of cardiac arrhythmia (Hill et al. 2009)

- ARNT1 morpholono knock-down protected against pericardial edema and reduced blood flow in zebrafish (Prasch et al. 2006)

- ARNT overexpression rescued cells from the inhibitory effect of hypoxia on AHR-mediated luciferase reporter activity; therefore, the mechanism of interference of the signaling cross-talk between AHR and hypoxia pathways is at least partially dependent on ARNT availability (Vorrink et al. 2014).

Key Event 2: Reduced HIF1α/ARNT dimerization (Essentiality = Moderate)

- Both ARNT–/– and HIF1α–/– mice display embryonic lethality with blocks in developmental angiogenesis and cardiovascular malformations (Iyer et al. 1998; Kozak et al. 1997; Maltepe et al. 1997; Ryan et al. 1998) demonstrating that signaling through the HIF-1 pathway is required for normal development of the cardiovascular system.

- The myocardium exhibits a reduced oxygen status during the later stages of coronary vascular development in chick and mouse embryos (Ivnitski-Steele et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2001)

- Rearing fish embryos in a hypoxic environment can modify cardiac activity, organ perfusion, and blood vessel formation (Pelster 2002)

- TCDD toxicity in fish resembles defects in hypoxia sensing (Prasch et al. 2004)

- Deviation in oxygen levels, below or above normal, during early chick embryogenesis results in abnormal coronary vasculature (Wikenheiser et al. 2009)

- Hypoxia stimulates vasculogenesis and regulates VEGF transcription in vivo and in vitro (Goldberg and Schneider 1994; Levy et al. 1995; Liu et al. 1995) (Goldberg 1994; LEVY 1995A; Liu 1995)

- Hypoxia stimulus can rescue TCDD inhibition of coronary vascular development in chick embryos (Ivnitski-Steele and Walker 2003)

Key Event 3: Reduced VEGF production (Essentiality = Moderate)

- Loss of a single VEGF-A allele in mice results in defective vascularization and early embryonic lethality (Carmeliet et al. 1996; Ferrara et al. 1996).

- Mice lacking VEGF isoforms 164 and 188 exhibit impaired myocardial angiogenesis and reduced contractility leading to ischemic cardiomyopathy (Carmeliet et al. 1999)

- During vasculogenesis, angioblasts are stimulated to proliferate and differentiate into endothelial cells by VEGF-A (Ivnitski-Steele and Walker 2005)

- Migration and assembly of epicardial angioblasts into coronary vessels is regulated by VEGF (Folkman 1992)

- Cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of VEGF in mice results in phenotype similar to TCDD toxicity (thinner ventricular walls, ventricle cavity dilation, and contractile dysfunction) (Giordano et al. 2001; Ivnitski-Steele and Walker 2003)

- Exogenous VEGF rescues the inhibitory effect of TCDD on vasculogenesis (Ivnitski-Steele and Walker 2003)

Key Event 4: Endothelial network impairment (Essentiality = Moderate)

- The epicardium is the source of angioblasts, which penetrate into the myocardium, providing the endothelial and mural cell progenitor populations that eventually form the entire coronary vasculature (Viragh et al. 1993; Vrancken Peeters et al. 1999)

- Sectioned and stained heart samples from patients with ischemic heart disease lack epicardial cells (Di et al. 2010)

- Juvenile mice with induced cardiovascular disease show altered heart morphology and function, including epithelial dysfunction (Kopf et al. 2008)

- In zebrafish, cardiotoxicity coincides with epicardium formation. Cardiotoxicity begins at 48 hours post fertilization (hpf; start of pre-epicardium formation) and starts to decline at 5 days post fertilization, which is about the time the initial epicardial cell layer is complete. Cardiotoxicity disappears at 2 weeks, after epicardium formation is complete. TCDD prevented the formation of the epicardial cell layer when exposed 4hpf, and blocked epicardial expansion from the ventricle to the atrium following exposure at 96hpf. These effects ultimately result in valve malformation, reduced heart size, impaired development of the bulbus arteriosus, decreased cardiac output, reduced end diastolic volume, decreased peripheral blood flow, edema and death (Plavicki et al. 2013).

- TCDD reduces human primary umbilical vein endothelial cells basal proliferation by 50% (Ivnitski-Steele and Walker 2005)

- The phenotype observed in chick embryos following TCDD exposure on day zero of incubation resembles that observed in vertebrate models in which the epicardium fails to form (Ivnitski-Steele and Walker 2005)

Key Event 5: Altered cardiovascular development/ function (Essentiality = Strong)

- The most common cause of infant death due to birth defects is congenital cardiovascular malformation (Kopf and Walker 2009)

- A significant reduction in embryo survival was observed in 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) exposed chick embryos, and was associated with heart failure resulting from altered heart morphology:

- Increased heart width and weight, increased muscle mass, enlarged left ventricle, thinner left ventricle wall, and increased ventricular trabeculation and ventricular septal defects (Walker et al. 1997).

- Changes in heart morphology consistent with dilated cardiomyopathy (decreased cardiac output and ventricular cavity expansion) were observed in chick embryos exposed to TCDD followed by progression to congestive heart failure edema (Walker and Catron 2000).

- Changes in heart morphology and decreases in cardiac output and peripheral blood flow precede heart failure in Zebrafish (Antkiewicz et al. 2005; Belair et al. 2001; Henry et al. 1997; Plavicki et al. 2013)

Cardiotoxic effects of strong AHR-agonists

| Zebrafish Embryo | Chicken Embryo | Mouse |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Embryo/Fetus

21 Days old

|

ANF= cardiac atrial natriuretic factor; an indicator of cardiac stress. Source: (Kopf and Walker 2009)

Weight of Evidence Summary

|

Key Event Relationship |

Weight of Evidence Is there a mechanistic relationship between KEup and KEdown consistent with established biological knowledge? |

Support for Biological Plausibility Strong: Extensive understanding of the KER based on previous documentation and broad acceptance. Moderate: KER is plausible based on analogy to accepted biological relationships, but scientific understanding is incomplete. Weak: Empirical support for association between KEs, but the structural or functional relationship between them is not understood. |

|

KER972: Activation, AhR leads to dimerization, AHR/ARNT |

Strong |

The mechanism of AHR-mediated transcriptional regulation is well understood (Fujii-Kuriyama and Kawajiri 2010). ARNT is a necessary dimerization partner for the transcriptional activation of AHR regulated genes (Hoffman et al. 1991; Poland et al. 1976). |

|

KER973: dimerization, AHR/ARNT leads to reduced dimerization, ARNT/HIF1-alpha |

Moderate |

ARNT is common dimerization partner for both AHR and HIF-1α. Gel-shift and coimmunoprecipitation experiments have shown that the AHR and HIF1α compete for ARNT in vitro, with approximately equal dimerization efficiencies (Schmidt and Bradfield 1996). A number of studies have shown a reduced response to hypoxia following AHR activation (Chan et al. 1999, Seifert et al. 2008, Ivnitski-Steele et al. 2004), however this effect is highly tissue specific; in cells where ARNT is abundant, it does not deplete due to hypoxia or AHR activation (Chan et al. 1999; Pollenz et al. 1999) |

|

KER974: reduced dimerization, ARNT/HIF1-alpha leads to reduced production, VEGF |

Strong |

The transcriptional control of VEGF by HIF-1 is well understood; The HIF-1 complex binds to the VEGF gene promoter, recruiting additional transcriptional factors and initiating VEGF transcription (Ahluwalia and Tarnawski 2012; Fong 2009) |

|

KER975: reduced production, VEGF leads to Impairment, Endothelial network |

Strong |

The importance of VEGF for endothelial network formation and integrity is clear (Ivnitski-Steele and Walker 2005); loss of a single VEGF-A allele results in defective vascularization and early embryonic lethality (Carmeliet et al. 1996; Ferrara et al. 1996). |

|

KER976: Impairment, Endothelial network leads to Altered, Cardiovascular development/function |

Moderate |

The importance of endothelial cell migration, proliferation and integrity in neovascularization and organogenesis is well documented. Development of vasculature into highly branched conduits needs to occur in numerous sites and in precise patterns to supply oxygen and nutrients to the rapidly expanding tissue of the embryo; aberrant regulation and coordination of angiogenic signals during development result in impaired organ development (Chung and Ferrara 2011; Ivnitski-Steele and Walker 2005). The extent to which the observed cardiovascular abnormalities are caused by deregulation of the underlying endothelial network remains unclear. |

|

KER1567: Altered, Cardiovascular development/function leads to Increase, Early Life Stage Mortality |

Strong |

The connection between altered cardiovascular developement during embryogenesis, diminished cardiac output and embryonic death have been well studied (Thakur et al. 2013; Kopf and Walker 2009). |

|

KER984: Activation, AhR leads to Increase, Early Life Stage Mortality |

Strong |

Differences in species sensitivity to dioxin-like compounds have been associated with differences in the AHR amino acid sequence in mammals, fish and birds; the identity of these amino acids in the AHR ligand binding domain affects DLC binding affinity, AHR transactivation and therefore toxicity (Farmahin et al. 2012; Head et al. 2008; Karchner et al. 2006; Mimura and Fujii-Kuriyama 2003; Wirgin et al. 2011). The predictive ability of an LRG assay measuring induction of AHR1-mediated gene expression was demonstrated by linear regression analysis comparing log-transformed LD50 values obtained from the literature to log-transformed PC20 values from the LRG assay (Farmahin et al. 2013; Manning et al. 2012) |

Quantitative Consideration

Summary Table

Provide an overall discussion of the quantitative information available for this AOP. Support calls for the individual relationships can be included in the Key Event Relationship table above.

The quantitative understanding of individual KERs in this AOP is weak; however, there is a strong correlation between the molecular initiating event (MIE: AHR activation) and adverse outcome (AO: embryolethality) in birds. This relationship is described in detail in KER984 ( Activation, AhR leads to Increase, Early Life Stage Mortality), found in the KER summary table. In brief, the AHR1 ligand binding domain (LBD) sequence alone could be used to predict DLC-induced embryolethality in a given bird species. The identity amino acids at two key positions within the LBD dictate the binding affinity of xenobiotics and therefore the strength of induction. AHR-mediated reporter gene induction can be measured using a luciferase reporter gene assay, the strength of which is correlated to the embryo-lethal dose of AHR aginists as shown below.

Figure 1. Linear regression analysis comparing LD50 values with PC20 (logLD50 = 0.79logPC20 + 0.51) values derived from luciferase reporter gene (LRG) assay concentration-response curves. Open symbols represent LRG data from wild-type chicken, ring-necked pheasant or Japanese quail AHR1 expression vectors. Closed symbols represent LRG data from mutant AHR1 (Source: Manning, G. E. et al. (2012). Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 263(3), 390-399.)

Uncertainties and Inconsistencies

Although crosstalk between AHR and HIF1α clearly exists, the nature of the relationship is still not clearly defined. It has been suggested that HIF1α and AHR do not competitively regulate each other for hetero-dimerization with ARNT, as ARNT is constitutively and abundantly expressed in cells and does not deplete due to hypoxia or AHR activation (Chan et al. 1999; Pollenz et al. 1999). In indirect support of this, a mutant zebrafish model (caAHR-dbd ) expressing an AHR that has lost DNA binding ability, but retains other functional aspects (such as dimerization and translocation) showed no signs of cardiotoxicity; this is in contrast to its counterpart (caAHR) in which sever cardiotoxicity was observed, having the same constitutive AHR expression level (Lanham et al. 2014). These results suggest that direct downstream transcription of AHR-regulated genes, not ARNT sequestration, is essential for cardiotoxicity. However, there is also considerable evidence demonstrating the inhibition of either AHR or HIF1α by activation of the other pathway. For example, TCDD inhibited the CoCl2 induction of a hypoxia response element (HRE) driven promoter and CoCl2 inhibited the TCDD induction of a dioxin response element (DRE) driven promoter, in Hep3B cells (Chan et al. 1999). TCDD also reduced HIF1α nuclear-localized staining in most areas of the heart in chick embryos (Wikenheiser et al. 2012), reduced the stabilization of HIF1α and HRE-mediated promoter activity in Hepa 1 cells and reduced hypoxia-mediated reporter gene activity in B-1 cells (Nie et al. 2001), whereas hypoxia inhibited AHR-mediated CYP1A1 induction in B-1 and Hepa 1 cells, but not H4IIE-luc (Nie et al. 2001). Some studies have shown that the effect of hypoxia on AHR mediated pathways is stronger than the reverse (Gassmann et al. 1997; Gradin et al. 1996; Nie et al. 2001; Prasch et al. 2004), which has been attributed to the stronger binding affinity of HIF1α to ARNT relative to AHR (Gradin et al. 1996). Contrary to this pattern, the combined exposure of juvenile orange spotted grouper to benzo[a]pyrine (BaP; an AHR agonist) and hypoxia, enhanced hypoxia-induced gene expression but did not alter BaP-induced gene expression (Yu et al. 2008). All in all, it appears the effect of cross-talk between AHR and HIF1α is highly dependent on tissue type and life stage, leading to seemingly contradictory results and making it difficult to elucidate a mechanism of action with high confidence.

There is significant evidence suggesting that sustained AHR activation during embryo development results in reduced cardiac VEGF expression (See KER pages for details); however, the opposite relationship has also been observed. In human microvascular endothelial cells, hexachlorobenzene (weak AHR agonist) exposure enhanced VEGF protein expression and secretion. TCDD induced VEGF-A transcription and production in retinal tissue of adult mice and in human retinal pigment epithelial cells (Takeuchi et al. 2009) and induced VEGF secretion from human bronchial epithelial cells (adult) (Tsai et al. 2015). It has been reported that the AHR/ARNT heterodimer binds to estrogen response elements, with mediation of the estrogen receptor (ER), and activates transcription of VEGF-A (Ohtake et al. 2003). The potential involvement of AHR in opposing regulatory cascades (directly inducing VEGF through ER and indirectly suppressing it by ARNT sequestration) helps explain the conflicting results found in the literature. Further complicating the picture is the potential for HIF-1-independent regulation of VEGF, as illustrated in an ARNT-deficient mutant cell line (Hepa1 C4) in which VEGF expression was only partially abrogated (Gassmann et al. 1997).

Alternate Pathways

Altered metabolism of the membrane lipid arachidonic acid (AA) by CYP1A enzymes is another potential mechanism of embryotoxicity. Induction of CYP1A is associated with increased production of AA epoxides that can lead to cytotoxicity and increased susceptibility to injury from oxidative stress due to increased production of oxygen radicals (Toraason et al. 1995). It has been suggested that cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) is essential in this toxic response as TCDD-induced morphological defects and edema in the heart were accompanied by COX-2 induction and were prevented with COX-2 inhibitors in fish (Dong et al. 2010; Teraoka et al. 2008). In chick embryos, TCDD-induced mortality, left ventricle enlargement and cardiac stress were prevented by selective COX-2 inhibition (Fujisawa et al. 2014). A non-genomic pathway (ie. ARNT-independent) was suggested as a mechanism for the AHR-mediated induction of COX-2 in which ligand-binding causes a rapid increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration, activating cytosolic phospholipase A2, inducing COX-2 expression and resulting in an inflammatory response (Matsumura 2009). Interestingly, VEGF-A mRNA was up-regulated 2.7-fold by TCDD and was unaffected by COX-2 inhibition (Fujisawa et al. 2014) Studies investigating the role of CYP1A induction in mediating vascular toxicity have been contradictory, with some studies demonstrating that CYP1A mediates vascular toxicity (Cantrell et al. 1996; Dong et al. 2002; Teraoka et al. 2003), others demonstrating that it does not have an effect (Carney et al. 2004; Hornung et al. 1999), and some showing it to play a protective role (Billiard et al. 2006; Brown et al. 2015). Overall, cardiotoxicity is unlikely a downstream effect of CYP1A induction, but its generation of ROS and therefore oxidative stress likely contributes to the toxicity. Finally, since AHR has a role in heart development that is independent of exogenous ligand-mediated activation, it has been suggested that exogenous AHR ligands sequester it away from its endogenous function (Carreira et al. 2015). Cardiotoxicity may be mediated by Homeobox protein NKX2-5, an essential cardiogenesis transcription factor, as its expression was decreased in AHR-null mice.

Considerations for Potential Applications of the AOP (optional)

This AOP was developed with the intended purpose of chemical screening as well as ecological risk assessment. There has recently been significant advances in the understanding of differences in avian sensitivity to AHR agonists, and a similar effort is underway for fish. Sequencing the AHR ligand binding domain of any bird species (and potentially fish species) allows for its classification as low, medium or high sensitivity, which aids in the chemical risk assessment of DLCs and other AHR agonists. There is also potential use for this AOP in risk management, as minimum allowable environmental levels can be customized to the sensitivity of the native species in the area under consideration.

References

1. Abbott, B. D., and Buckalew, A. R. (2000). Placental defects in ARNT-knockout conceptus correlate with localized decreases in VEGF-R2, Ang-1, and Tie-2. Dev. Dyn. 219(4), 526-538.

2. Antkiewicz, D. S., Burns, C. G., Carney, S. A., Peterson, R. E., and Heideman, W. (2005). Heart malformation is an early response to TCDD in embryonic zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 84(2), 368-377.

3. Aragon, A. C., Kopf, P. G., Campen, M. J., Huwe, J. K., and Walker, M. K. (2008). In utero and lactational 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin exposure: effects on fetal and adult cardiac gene expression and adult cardiac and renal morphology. Toxicol. Sci. 101(2), 321-330.

4. Bello, S. M., Heideman, W., and Peterson, R. E. (2004). 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin inhibits regression of the common cardinal vein in developing zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 78(2), 258-266.

5. Bertazzi, P. A., Bernucci, I., Brambilla, G., Consonni, D., and Pesatori, A. C. (1998). The Seveso studies on early and long-term effects of dioxin exposure: a review. Environ. Health Perspect. 106 Suppl 2, 625-633.

6. Billiard, S. M., Timme-Laragy, A. R., Wassenberg, D. M., Cockman, C., and Di Giulio, R. T. (2006). The role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway in mediating synergistic developmental toxicity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 92(2), 526-536.

7. Brown, D. R., Clark, B. W., Garner, L. V., and Di Giulio, R. T. (2015). Zebrafish cardiotoxicity: the effects of CYP1A inhibition and AHR2 knockdown following exposure to weak aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists. Environ Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 22(11), 8329-8338.

8. Cantrell, S. M., Lutz, L. H., Tillitt, D. E., and Hannink, M. (1996). Embryotoxicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD): the embryonic vasculature is a physiological target for TCDD-induced DNA damage and apoptotic cell death in Medaka (Orizias latipes). Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 141(1), 23-34.

9. Carmeliet, P., Ferreira, V., Breier, G., Pollefeyt, S., Kieckens, L., Gertsenstein, M., Fahrig, M., Vandenhoeck, A., Harpal, K., Eberhardt, C., Declercq, C., Pawling, J., Moons, L., Collen, D., Risau, W., and Nagy, A. (1996). Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature 380(6573), 435-439.

10. Carmeliet, P., Ng, Y. S., Nuyens, D., Theilmeier, G., Brusselmans, K., Cornelissen, I., Ehler, E., Kakkar, V. V., Stalmans, I., Mattot, V., Perriard, J. C., Dewerchin, M., Flameng, W., Nagy, A., Lupu, F., Moons, L., Collen, D., D'Amore, P. A., and Shima, D. T. (1999). Impaired myocardial angiogenesis and ischemic cardiomyopathy in mice lacking the vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms VEGF164 and VEGF188. Nat. Med. 5(5), 495-502.

11. Carney, S. A., Peterson, R. E., and Heideman, W. (2004). 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor/aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator pathway causes developmental toxicity through a CYP1A-independent mechanism in zebrafish. Mol. Pharmacol. 66(3), 512-521.

12. Carney, S. A., Prasch, A. L., Heideman, W., and Peterson, R. E. (2006). Understanding dioxin developmental toxicity using the zebrafish model. Birth Defects Res. A Clin Mol. Teratol. 76(1), 7-18.

13. Carreira, V. S., Fan, Y., Wang, Q., Zhang, X., Kurita, H., Ko, C. I., Naticchioni, M., Jiang, M., Koch, S., Medvedovic, M., Xia, Y., Rubinstein, J., and Puga, A. (2015). Ah Receptor Signaling Controls the Expression of Cardiac Development and Homeostasis Genes. Toxicol. Sci. 147(2), 425-435.

14. Carro, T., Dean, K., and Ottinger, M. A. (2013). Effects of an environmentally relevant polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) mixture on embryonic survival and cardiac development in the domestic chicken. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 23(6), 1325-1331.

15. Chan, W. K., Yao, G., Gu, Y. Z., and Bradfield, C. A. (1999). Cross-talk between the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and hypoxia inducible factor signaling pathways. Demonstration of competition and compensation. J Biol. Chem. 274(17), 12115-12123.

16. Di, M. F., Castaldo, C., Nurzynska, D., Romano, V., Miraglia, R., and Montagnani, S. (2010). Epicardial cells are missing from the surface of hearts with ischemic cardiomyopathy: a useful clue about the self-renewal potential of the adult human heart? Int. J Cardiol. 145(2), e44-e46.

17. Dong, W., Matsumura, F., and Kullman, S. W. (2010). TCDD induced pericardial edema and relative COX-2 expression in medaka (Oryzias Latipes) embryos. Toxicol. Sci. 118(1), 213-223.

18. Dong, W., Teraoka, H., Yamazaki, K., Tsukiyama, S., Imani, S., Imagawa, T., Stegeman, J. J., Peterson, R. E., and Hiraga, T. (2002). 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin toxicity in the zebrafish embryo: local circulation failure in the dorsal midbrain is associated with increased apoptosis. Toxicol. Sci. 69(1), 191-201.

19. Ferrara, N., Carver-Moore, K., Chen, H., Dowd, M., Lu, L., O'Shea, K. S., Powell-Braxton, L., Hillan, K. J., and Moore, M. W. (1996). Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature 380(6573), 439-442.

20. Flesch-Janys, D., Berger, J., Gurn, P., Manz, A., Nagel, S., Waltsgott, H., and Dwyer, J. H. (1995). Exposure to polychlorinated dioxins and furans (PCDD/F) and mortality in a cohort of workers from a herbicide-producing plant in Hamburg, Federal Republic of Germany. Am. J Epidemiol. 142(11), 1165-1175.

21. Fujisawa, N., Nakayama, S. M., Ikenaka, Y., and Ishizuka, M. (2014). TCDD-induced chick cardiotoxicity is abolished by a selective cyclooxygenase2 (COX2) inhibitor NS398. Arch. Toxicol. 88(9), 1739-1748.

22. Gassmann, M., Kvietikova, I., Rolfs, A., and Wenger, R. H. (1997). Oxygen- and dioxin-regulated gene expression in mouse hepatoma cells. Kidney Int. 51(2), 567-574.

23. Giordano, F. J., Gerber, H. P., Williams, S. P., VanBruggen, N., Bunting, S., Ruiz-Lozano, P., Gu, Y., Nath, A. K., Huang, Y., Hickey, R., Dalton, N., Peterson, K. L., Ross, J., Jr., Chien, K. R., and Ferrara, N. (2001). A cardiac myocyte vascular endothelial growth factor paracrine pathway is required to maintain cardiac function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 98(10), 5780-5785.

24. Goldberg, M. A., and Schneider, T. J. (1994). Similarities between the oxygen-sensing mechanisms regulating the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and erythropoietin. J. Biol. Chem. 269(6), 4355-4359.

25. Goodale, B. C., La Du, J. K., Bisson, W. H., Janszen, D. B., Waters, K. M., and Tanguay, R. L. (2012). AHR2 mutant reveals functional diversity of aryl hydrocarbon receptors in zebrafish. PLoS. One. 7(1), e29346.

26. Gradin, K., McGuire, J., Wenger, R. H., Kvietikova, I., fhitelaw, M. L., Toftgard, R., Tora, L., Gassmann, M., and Poellinger, L. (1996). Functional interference between hypoxia and dioxin signal transduction pathways: competition for recruitment of the Arnt transcription factor. Mol. Cell Biol. 16(10), 5221-5231.

27. Higginbotham, G. R., Huang, A., Firestone, D., Verrett, J., Ress, J., and Campbell, A. D. (1968). Chemical and toxicological evaluations of isolated and synthetic chloro derivatives of dibenzo-p-dioxin. Nature 220(5168), 702-703.

28. Hill, A. J., Heiden, T. C., Heideman, W., and Peterson, R. E. (2009). Potential roles of Arnt2 in zebrafish larval development. Zebrafish. 6(1), 79-91.

29. Hornung, M. W., Spitsbergen, J. M., and Peterson, R. E. (1999). 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin alters cardiovascular and craniofacial development and function in sac fry of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Toxicol. Sci. 47(1), 40-51.

30. Huuskonen, H., Unkila, M., Pohjanvirta, R., and Tuomisto, J. (1994). Developmental toxicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in the most TCDD-resistant and -susceptible rat strains. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 124(2), 174-180.

31. Ichihara, S., Yamada, Y., Ichihara, G., Nakajima, T., Li, P., Kondo, T., Gonzalez, F. J., and Murohara, T. (2007). A role for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in regulation of ischemia-induced angiogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27(6), 1297-1304.

32. Ivnitski, I., Elmaoued, R., and Walker, M. K. (2001). 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) inhibition of coronary development is preceded by a decrease in myocyte proliferation and an increase in cardiac apoptosis. Teratology 64(4), 201-212.

33. Ivnitski-Steele, I., and Walker, M. K. (2005). Inhibition of neovascularization by environmental agents. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 5(2), 215-226.

34. Ivnitski-Steele, I. D., Friggens, M., Chavez, M., and Walker, M. K. (2005). 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) inhibition of coronary vasculogenesis is mediated, in part, by reduced responsiveness to endogenous angiogenic stimuli, including vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A). Birth Defects Res. A Clin Mol. Teratol. 73(6), 440-446.

35. Ivnitski-Steele, I. D., Sanchez, A., and Walker, M. K. (2004). 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin reduces myocardial hypoxia and vascular endothelial growth factor expression during chick embryo development. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 70(2), 51-58.

36. Ivnitski-Steele, I. D., and Walker, M. K. (2003). Vascular endothelial growth factor rescues 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin inhibition of coronary vasculogenesis. Birth Defects Res. A Clin Mol. Teratol. 67(7), 496-503.

37. Iyer, N. V., Kotch, L. E., Agani, F., Leung, S. W., Laughner, E., Wenger, R. H., Gassmann, M., Gearhart, J. D., Lawler, A. M., Yu, A. Y., and Semenza, G. L. (1998). Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes Dev. 12(2), 149-162.

38. Kopf, P. G., and Walker, M. K. (2009). Overview of developmental heart defects by dioxins, PCBs, and pesticides. J. Environ. Sci. Health C. Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev. 27(4), 276-285.

39. Kozak, K. R., Abbott, B., and Hankinson, O. (1997). ARNT-deficient mice and placental differentiation. Dev. Biol. 191(2), 297-305.

40. Lanham, K. A., Plavicki, J., Peterson, R. E., and Heideman, W. (2014). Cardiac myocyte-specific AHR activation phenocopies TCDD-induced toxicity in zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 141(1), 141-154.

41. Lee, Y. M., Jeong, C. H., Koo, S. Y., Son, M. J., Song, H. S., Bae, S. K., Raleigh, J. A., Chung, H. Y., Yoo, M. A., and Kim, K. W. (2001). Determination of hypoxic region by hypoxia marker in developing mouse embryos in vivo: a possible signal for vessel development. Dev. Dyn. 220(2), 175-186.

42. Levy, A. P., Levy, N. S., Wegner, S., and Goldberg, M. A. (1995). Transcriptional regulation of the rat vascular endothelial growth factor gene by hypoxia. J Biol. Chem 270(22), 13333-13340.

43. Liu, Y., Cox, S. R., Morita, T., and Kourembanas, S. (1995). Hypoxia regulates vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression in endothelial cells. Identification of a 5' enhancer. Circ. Res. 77(3), 638-643.

44. Loffredo, C. A., Silbergeld, E. K., Ferencz, C., and Zhang, J. (2001). Association of transposition of the great arteries in infants with maternal exposures to herbicides and rodenticides. Am. J Epidemiol. 153(6), 529-536.

45. Maltepe, E., Schmidt, J. V., Baunoch, D., Bradfield, C. A., and Simon, M. C. (1997). Abnormal angiogenesis and responses to glucose and oxygen deprivation in mice lacking the protein ARNT. Nature 386(6623), 403-407.

46. Manning, G. E., Farmahin, R., Crump, D., Jones, S. P., Klein, J., Konstantinov, A., Potter, D., and Kennedy, S. W. (2012). A luciferase reporter gene assay and aryl hydrocarbon receptor 1 genotype predict the embryolethality of polychlorinated biphenyls in avian species. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 263(3), 390-399.

47. Matsumura, F. (2009). The significance of the nongenomic pathway in mediating inflammatory signaling of the dioxin-activated Ah receptor to cause toxic effects. Biochem. Pharmacol. 77(4), 608-626.

48. Metcalfe, L. D. (1972). Proposed source of chick edema factor. J Assoc. Off Anal. Chem. 55(3), 542-546.

49. Nie, M., Blankenship, A. L., and Giesy, J. P. (2001). Interactions between aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and hypoxia signaling pathways. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 10(1-2), 17-27.

50. Ohtake, F., Takeyama, K., Matsumoto, T., Kitagawa, H., Yamamoto, Y., Nohara, K., Tohyama, C., Krust, A., Mimura, J., Chambon, P., Yanagisawa, J., Fujii-Kuriyama, Y., and Kato, S. (2003). Modulation of oestrogen receptor signalling by association with the activated dioxin receptor. Nature 423(6939), 545-550.

51. Patterson, A. J., and Zhang, L. (2010). Hypoxia and fetal heart development. Curr. Mol. Med. 10(7), 653-666. 52. Pelster, B. (2002). Developmental plasticity in the cardiovascular system of fish, with special reference to the zebrafish. Comp Biochem. Physiol A Mol. Integr. Physiol 133(3), 547-553.

53. Plavicki, J., Hofsteen, P., Peterson, R. E., and Heideman, W. (2013). Dioxin inhibits zebrafish epicardium and proepicardium development. Toxicol. Sci. 131(2), 558-567.

54. Pollenz, R. S., Davarinos, N. A., and Shearer, T. P. (1999). Analysis of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated signaling during physiological hypoxia reveals lack of competition for the aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator transcription factor. Mol. Pharmacol. 56(6), 1127-1137.

55. Prasch, A. L., Andreasen, E. A., Peterson, R. E., and Heideman, W. (2004). Interactions between 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) and hypoxia signaling pathways in Zebrafish: Hypoxia decreases responses to TCDD in Zebrafish embryos. Toxicol. Sci. 78(1), 68-77.

56. Prasch, A. L., Tanguay, R. L., Mehta, V., Heideman, W., and Peterson, R. E. (2006). Identification of zebrafish ARNT1 homologs: 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin toxicity in the developing zebrafish requires ARNT1. Mol. Pharmacol. 69(3), 776-787.

57. Prasch, A. L., Teraoka, H., Carney, S. A., Dong, W., Hiraga, T., Stegeman, J. J., Heideman, W., and Peterson, R. E. (2003). Aryl hydrocarbon receptor 2 mediates 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin developmental toxicity in zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 76(1), 138-150.

58. Roman, A. C., Carvajal-Gonzalez, J. M., Rico-Leo, E. M., and Fernandez-Salguero, P. M. (2009). Dioxin receptor deficiency impairs angiogenesis by a mechanism involving VEGF-A depletion in the endothelium and transforming growth factor-beta overexpression in the stroma. J Biol. Chem 284(37), 25135-25148.

59. Ryan, H. E., Lo, J., and Johnson, R. S. (1998). HIF-1 alpha is required for solid tumor formation and embryonic vascularization. EMBO J 17(11), 3005-3015.

60. SCHMITTLE, S. C., EDWARDS, H. M., and MORRIS, D. (1958). A disorder of chickens probably due to a toxic feed; preliminary report. J Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 132(5), 216-219.

61. Takeuchi, A., Takeuchi, M., Oikawa, K., Sonoda, K. H., Usui, Y., Okunuki, Y., Takeda, A., Oshima, Y., Yoshida, K., Usui, M., Goto, H., and Kuroda, M. (2009). Effects of dioxin on vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production in the retina associated with choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50(7), 3410-3416.

62. Teraoka, H., Dong, W., Tsujimoto, Y., Iwasa, H., Endoh, D., Ueno, N., Stegeman, J. J., Peterson, R. E., and Hiraga, T. (2003). Induction of cytochrome P450 1A is required for circulation failure and edema by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in zebrafish. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 304(2), 223-228.

63. Teraoka, H., Kubota, A., Kawai, A., and Hiraga, T. (2008). Prostanoid Signaling Mediates Circulation Failure Caused by TCDD in Developing Zebrafish. Interdiscip Stud Environ Chem 1, 60-80.

64. Thackaberry, E. A., Jiang, Z., Johnson, C. D., Ramos, K. S., and Walker, M. K. (2005a). Toxicogenomic profile of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in the murine fetal heart: modulation of cell cycle and extracellular matrix genes. Toxicol. Sci 88(1), 231-241.

65. Thackaberry, E. A., Nunez, B. A., Ivnitski-Steele, I. D., Friggins, M., and Walker, M. K. (2005b). Effect of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on murine heart development: alteration in fetal and postnatal cardiac growth, and postnatal cardiac chronotropy. Toxicol. Sci 88(1), 242-249.

66. Toraason, M., Wey, H., Woolery, M., Plews, P., and Hoffmann, P. (1995). Arachidonic acid supplementation enhances hydrogen peroxide induced oxidative injury of neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 29(5), 624-628. 67. Trinh, L. A., and Stainier, D. Y. (2004). Fibronectin regulates epithelial organization during myocardial migration in zebrafish. Dev. Cell 6(3), 371-382.

68. Tsai, M. J., Wang, T. N., Lin, Y. S., Kuo, P. L., Hsu, Y. L., and Huang, M. S. (2015). Aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists upregulate VEGF secretion from bronchial epithelial cells. J Mol. Med. (Berl) 93(11), 1257-1269.

69. Viragh, S., Gittenberger-de Groot, A. C., Poelmann, R. E., and Kalman, F. (1993). Early development of quail heart epicardium and associated vascular and glandular structures. Anat. Embryol. (Berl) 188(4), 381-393.

70. Vorrink, S. U., Severson, P. L., Kulak, M. V., Futscher, B. W., and Domann, F. E. (2014). Hypoxia perturbs aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling and CYP1A1 expression induced by PCB 126 in human skin and liver-derived cell lines. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 274(3), 408-416.

71. Vrancken Peeters, M. P., Gittenberger-de Groot, A. C., Mentink, M. M., and Poelmann, R. E. (1999). Smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts of the coronary arteries derive from epithelial-mesenchymal transformation of the epicardium. Anat. Embryol. (Berl) 199(4), 367-378.

72. Walker, M. K., and Catron, T. F. (2000). Characterization of cardiotoxicity induced by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and related chemicals during early chick embryo development. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 167(3), 210-221.

73. Walker, M. K., Pollenz, R. S., and Smith, S. M. (1997). Expression of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and AhR nuclear translocator during chick cardiogenesis is consistent with 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced heart defects. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 143(2), 407-419.

74. Wikenheiser, J., Karunamuni, G., Sloter, E., Walker, M. K., Roy, D., Wilson, D. L., and Watanabe, M. (2013). Altering HIF-1alpha Through 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-Dioxin (TCDD) Exposure Affects Coronary Vessel Development. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 13(2), 161–167

75. Wikenheiser, J., Wolfram, J. A., Gargesha, M., Yang, K., Karunamuni, G., Wilson, D. L., Semenza, G. L., Agani, F., Fisher, S. A., Ward, N., and Watanabe, M. (2009). Altered hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha expression levels correlate with coronary vessel anomalies. Dev. Dyn. 238(10), 2688-2700.

76. Yu, R. M., Ng, P. K., Tan, T., Chu, D. L., Wu, R. S., and Kong, R. Y. (2008). Enhancement of hypoxia-induced gene expression in fish liver by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligand, benzo[a]pyrene (BaP). Aquat. Toxicol. 90(3), 235-242. 78. Fujii-Kuriyama, Y., and Kawajiri, K. (2010). Molecular mechanisms of the physiological functions of the aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor, a multifunctional regulator that senses and responds to environmental stimuli. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 86(1), 40-53.

77. Hoffman, E. C., Reyes, H., Chu, F. F., Sander, F., Conley, L. H., Brooks, B. A., and Hankinson, O. (1991). Cloning of a factor required for activity of the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Science 252(5008), 954-958.

78. Poland, A., Glover, E., and Kende, A. S. (1976). Stereospecific, high affinity binding of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin by hepatic cytosol. Evidence that the binding species is receptor for induction of aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 251(16), 4936-4946.

79. Schmidt, J. V., and Bradfield, C. A. (1996). Ah receptor signaling pathways. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 55-89.

80. Seifert, A., Katschinski, D. M., Tonack, S., Fischer, B., and Navarrete, S. A. (2008). Significance of prolyl hydroxylase 2 in the interference of aryl hydrocarbon receptor and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha signaling. Chem Res. Toxicol. 21(2), 341-348.

81. Ahluwalia, A., and Tarnawski, A. S. (2012). Critical role of hypoxia sensor--HIF-1alpha in VEGF gene activation. Implications for angiogenesis and tissue injury healing. Curr. Med. Chem 19(1), 90-97.

82. Fong, G. H. (2009). Regulation of angiogenesis by oxygen sensing mechanisms. J Mol. Med. (Berl) 87(6), 549-560.

83. Chung, A. S., and Ferrara, N. (2011). Developmental and pathological angiogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 27, 563-584.

84. Thakur, V., Fouron, J. C., Mertens, L., and Jaeggi, E. T. (2013). Diagnosis and management of fetal heart failure. Can. J Cardiol. 29(7), 759-767.

85. Henshel, D. S., Hehn, B. M., Vo, M. T., and Steeves, J. D. (1993). A short-term test for dioxin teratogenicity using chicken embryos. In Environmental Toxicology and Risk Assessment: Volume 2 (J.W.Gorsuch, F.J.Dwyer, C.G.Ingersoll, and T.W.La Point, Eds.), pp. 159-174. American Society of Testing and materials, Philedalphia.

86. Cheung, M. O., Gilbert, E. F., and Peterson, R. E. (1981). Cardiovascular teratogenicity of 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in the chick embryo. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 61(2), 197-204.

87. Canga, L., Paroli, L., Blanck, T. J., Silver, R. B., and Rifkind, A. B. (1993). 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin increases cardiac myocyte intracellular calcium and progressively impairs ventricular contractile responses to isoproterenol and to calcium in chick embryo hearts. Mol. Pharmacol. 44(6), 1142-1151.

88. Belair, C. D., Peterson, R. E., and Heideman, W. (2001). Disruption of erythropoiesis by dioxin in the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 222(4), 581-594.

89. Henry, T. R., Spitsbergen, J. M., Hornung, M. W., Abnet, C. C., and Peterson, R. E. (1997). Early life stage toxicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 142(1), 56-68.

90. Farmahin, R., Wu, D., Crump, D., Hervé, J.C., Jones, S.P., Hahn, M.E., Karchner, S.I., Giesy, J.P., Bursian, S.J., Zwiernik, M.J., Kennedy, S.W. (2012) Sequence and in vitro function of chicken, ring-necked pheasant, and Japanese quail AHR1 predict in vivo sensitivity to dioxins. Environ Sci Technol. 46(5), 2967-75.

91. Farmahin, R., Manning, G. E., Crump, D., Wu, D., Mundy, L. J., Jones, S. P., Hahn, M. E., Karchner, S. I., Giesy, J. P., Bursian, S. J., Zwiernik, M. J., Fredricks, T. B., and Kennedy, S. W. (2013). Amino acid sequence of the ligand-binding domain of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor 1 predicts sensitivity of wild birds to effects of dioxin-like compounds. Toxicol. Sci. 131(1), 139-152.

92. Head, J. A., Hahn, M. E., and Kennedy, S. W. (2008). Key amino acids in the aryl hydrocarbon receptor predict dioxin sensitivity in avian species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42(19), 7535-7541.

93. Karchner, S. I., Franks, D. G., Kennedy, S. W., and Hahn, M. E. (2006). The molecular basis for differential dioxin sensitivity in birds: Role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 103(16), 6252-6257.

94. Mimura, J., and Fujii-Kuriyama, Y. (2003). Functional role of AhR in the expression of toxic effects by TCDD. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - General Subjects 1619, 263-268.

95. Wirgin, I., Roy, N. K., Loftus, M., Chambers, R. C., Franks, D. G., and Hahn, M. E. (2011). Mechanistic basis of resistance to PCBs in Atlantic tomcod from the Hudson River. Science 331, 1322-1325.

96. Brunström, B. (1988). Sensitivity of embryos from duck, goose, herring gull, and various chicken breeds to 3,3',4,4'-tetrachlorobiphenyl. Poultry science 67, 52-57.

97. Brunström, B., and Andersson, L. (1988). Toxicity and 7-ethoxyresorufin O-deethylase-inducing potency of coplanar polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in chick embryos. Archives of Toxicology 62, 263-266.

98. Di, M. F., Castaldo, C., Nurzynska, D., Romano, V., Miraglia, R., and Montagnani, S. (2010). Epicardial cells are missing from the surface of hearts with ischemic cardiomyopathy: a useful clue about the self-renewal potential of the adult human heart? Int. J Cardiol. 145(2), e44-e46.

99. Wang Q, Chen J, Ko C-I, Fan Y, Carreira V, Chen Y et al. (2013) Disruption of aryl hydrocarbon receptor

homeostatic levels during embryonic stem cell differentiation alters expression of homeobox transcription factors that control cardiomyogenesis. Environ Health Persp. 121:1334–43. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307297

100. Kawakami, T.; Ishimura, R.; Nohara, K.; Takeda, K.; Tohyama, C. and Ohsako, S. (2005) Differential susceptibilities of Holtzman and Sprague–Dawley rats to fetal death and placental dysfunction induced by

2,3,7,8-teterachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) despite the identical primary structure of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 212: 224 – 236.

101. E.A. Hassoun; A.C. Walter; N.Z. Alsharif and S.J. Stohs (1997) Modulation of TCDD-induced fetotoxicity and oxidative stress in embryonic and placental tissues of C57BL:6J mice by vitamin E succinate and ellagic acid. Toxicology 124: 27-37.

102. G. L. Sparschu; F. L. Dunn and V. K. Rowe (1971) Study of the Teratogenicity of 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in the Rat Fd Cosmet. ToxicoL 9: 405-412.

103. Debdas Mukerjee (1998) Health Impact of Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-dioxins: A Critical Review, Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 48:2, 157-165, DOI: 10.1080/10473289.1998.10463655

Appendix 1

List of MIEs in this AOP

Event: 18: Activation, AhR

Short Name: Activation, AhR

Key Event Component

| Process | Object | Action |

|---|---|---|

| aryl hydrocarbon receptor activity | aryl hydrocarbon receptor | increased |

AOPs Including This Key Event

| AOP ID and Name | Event Type |

|---|---|

| Aop:21 - aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation leading to early life stage mortality, via increased COX-2 | MolecularInitiatingEvent |

| Aop:57 - AhR activation leading to hepatic steatosis | MolecularInitiatingEvent |

| Aop:131 - Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation leading to uroporphyria | MolecularInitiatingEvent |

| Aop:150 - Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation leading to early life stage mortality, via reduced VEGF | MolecularInitiatingEvent |

Stressors

| Name |

|---|

| Benzidine |

| Dibenzo-p-dioxin |

| Polychlorinated biphenyl |

| Polychlorinated dibenzofurans |

| Hexachlorobenzene |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) |

Biological Context

| Level of Biological Organization |

|---|

| Molecular |

Evidence for Perturbation by Stressor

Overview for Molecular Initiating Event

The AHR can be activated by several structurally diverse chemicals, but binds preferentially to planar halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Dioxin-like compounds (DLCs), which include polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs), polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs) and certain polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), are among the most potent AHR ligands[38]. Only a subset of PCDD, PCDF and PCB congeners has been shown to bind to the AHR and cause toxic effects to those elicited by TCDD. Until recently, TCDD was considered to be the most potent DLC in birds[39]; however, recent reports indicate that 2,3,4,7,8-pentachlorodibenzofuran (PeCDF) is more potent than TCDD in some species of birds.[40][13][41][21][42][43] When screened for their ability to induce aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase (AHH) activity, dioxins with chlorine atoms at a minimum of three out of the four lateral ring positions, and with at least one non-chlorinated ring position are the most active[44]. Of the dioxin-like PCBs, non-ortho congeners are the most toxicologically active, while mono-ortho PCBs are generally less potent[45][9]. Chlorine substitution at ortho positions increases the energetic costs of assuming the coplanar conformation required for binding to the AHR [45]. Thus, a smaller proportion of mono-ortho PCB molecules are able to bind to the AHR and elicit toxic effects, resulting in reduced potency of these congeners. Other PCB congeners, such as di-ortho substituted PCBs, are very weak AHR agonists and do not likely contribute to dioxin-like effects [9].

- Contrary to studies of birds and mammals, even the most potent mono-ortho PCBs bind to AhRs of fishes with very low affinity, if at all (Abnet et al 1999; Doering et al 2014; 2015; Eisner et al 2016; Van den Berg et al 1998).

The role of the AHR in mediating the toxic effects of planar hydrophobic contaminants has been well studied, however the endogenous role of the AHR is less clear [1]. Some endogenous and natural substances, including prostaglandin PGG2 and the tryptophan derivatives indole-3-carbinol, 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole (FICZ) and kynurenic acid can bind to and activate the AHR. [6][46][47][48][49] The AHR is thought to have important endogenous roles in reproduction, liver and heart development, cardiovascular function, immune function and cell cycle regulation [50][38][51][52][53][54][46][55][56][57] and activation of the AHR by DLCs may therefore adversely affect these processes.

Dibenzo-p-dioxin

Denison, M. S., Soshilov, A. A., He, G., DeGroot, D. E., and Zhao, B. (2011). Exactly the same but different: promiscuity and diversity in the molecular mechanisms of action of the aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor. Toxicol.Sci. 124, 1-22.

Polychlorinated biphenyl

Of the dioxin-like PCBs, non-ortho congeners are the most toxicologically active, while mono-ortho PCBs are generally less potent (McFarland and Clarke 1989; Safe 1994). Chlorine substitution at ortho positions increases the energetic costs of assuming the coplanar conformation required for binding to the AHR (McFarland and Clarke 1989). Thus, a smaller proportion of mono-ortho PCB molecules are able to bind to the AHR and elicit toxic effects, resulting in reduced potency of these congeners. Other PCB congeners, such as di-ortho substituted PCBs, are very weak AHR agonists and do not likely contribute to dioxin-like effects (Safe 1994).

Safe, S. (1994). Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): Environmental impact, biochemical and toxic responses, and implications for risk assessment. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 24, 87-149.

McFarland, V. A., and Clarke, J. U. (1989). Environmental occurrence, abundance, and potential toxicity of polychlorinated biphenyl congeners: Considerations for a congener-specific analysis. Environ.Health Perspect. 81, 225-239.

Polychlorinated dibenzofurans

Denison, M. S., Soshilov, A. A., He, G., DeGroot, D. E., and Zhao, B. (2011). Exactly the same but different: promiscuity and diversity in the molecular mechanisms of action of the aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor. Toxicol.Sci. 124, 1-22.

Hexachlorobenzene

Cripps, D. J., Peters, H. A., Gocmen, A., and Dogramici, I. (1984) Porphyria turcica due to hexachlorobenzene: a 20 to 30 year follow-up study on 204 patients. Br. J Dermatol. 111 (4), 413-422.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

PAHs are pontent AHR agonists, but due to their rapid metabolism, they cause a transient alteration in AHR-mediated gene expression; this property results in a very different toxicity profile relative to persistent AHR-agonists such as dioxin-like compounds (Denison et al. 2011).

Denison, M. S., Soshilov, A. A., He, G., DeGroot, D. E., and Zhao, B. (2011). Exactly the same but different: promiscuity and diversity in the molecular mechanisms of action of the aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor. Toxicol.Sci. 124, 1-22.

Domain of Applicability

| Term | Scientific Term | Evidence | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| zebra danio | Danio rerio | High | NCBI |

| Gallus gallus | Gallus gallus | High | NCBI |

| Pagrus major | Pagrus major | High | NCBI |

| Acipenser transmontanus | Acipenser transmontanus | High | NCBI |

| Acipenser fulvescens | Acipenser fulvescens | High | NCBI |

| rainbow trout | Oncorhynchus mykiss | High | NCBI |

| Salmo salar | Salmo salar | High | NCBI |

| Xenopus laevis | Xenopus laevis | High | NCBI |

| Ambystoma mexicanum | Ambystoma mexicanum | High | NCBI |

| Phasianus colchicus | Phasianus colchicus | High | NCBI |

| Coturnix japonica | Coturnix japonica | High | NCBI |

| mouse | Mus musculus | High | NCBI |

| rat | Rattus norvegicus | High | NCBI |

| human | Homo sapiens | High | NCBI |

| Microgadus tomcod | Microgadus tomcod | High | NCBI |

| Life Stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Embryo | High |

| Development | High |

| All life stages | High |

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Unspecific | High |

The AHR structure has been shown to contribute to differences in species sensitivity to DLCs in several animal models. In 1976, a 10-fold difference was reported between two strains of mice (non-responsive DBA/2 mouse, and responsive C57BL/6 14 mouse) in CYP1A induction, lethality and teratogenicity following TCDD exposure[3]. This difference in dioxin sensitivity was later attributed to a single nucleotide polymorphism at position 375 (the equivalent position of amino acid residue 380 in chicken) in the AHR LBD[30][19][31]. Several other studies reported the importance of this amino acid in birds and mammals[32][30][22][33][34][35][31][36]. It has also been shown that the amino acid at position 319 (equivalent to 324 in chicken) plays an important role in ligand-binding affinity to the AHR and transactivation ability of the AHR, due to its involvement in LBD cavity volume and its steric effect[35]. Mutation at position 319 in the mouse eliminated AHR DNA binding[35].

The first study that attempted to elucidate the role of avian AHR1 domains and key amino acids within avian AHR1 in avian differential sensitivity was performed by Karchner et al.[22]. Using chimeric AHR1 constructs combining three AHR1 domains (DBD, LBD and TAD) from the chicken (highly sensitive to DLC toxicity) and common tern (resistant to DLC toxicity), Karchner and colleagues[22], showed that amino acid differences within the LBD were responsible for differences in TCDD sensitivity between the chicken and common tern. More specifically, the amino acid residues found at positions 324 and 380 in the AHR1 LBD were associated with differences in TCDD binding affinity and transactivation between the chicken (Ile324_Ser380) and common tern (Val324_Ala380) receptors[22]. Since the Karchner et al. (2006) study was conducted, the predicted AHR1 LBD amino acid sequences were been obtained for over 85 species of birds and 6 amino acid residues differed among species[14][37] . However, only the amino acids at positions 324 and 380 in the AHR1 LBD were associated with differences in DLC toxicity in ovo and AHR1-mediated gene expression in vitro[14][37][16]. These results indicate that avian species can be divided into one of three AHR1 types based on the amino acids found at positions 324 and 380 of the AHR1 LBD: type 1 (Ile324_Ser380), type 2 (Ile324_Ala380) and type 3 (Val324_Ala380)[14][37][16].

- Little is known about differences in binding affinity of AhRs and how this relates to sensitivity in non-avian taxa.

- Low binding affinity for DLCs of AhR1s of African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) and axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) has been suggested as a mechanism for tolerance of these amphibians to DLCs (Lavine et al 2005; Shoots et al 2015).

- Among reptiles, only AhRs of American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) have been investigated and little is known about the sensitivity of American alligator or other reptiles to DLCs (Oka et al 2016).

- Among fishes, great differences in sensitivity to DLCs are known both for AhRs and for embryos among species that have been tested (Doering et al 2013; 2014).

- Differences in binding affinity of the AhR2 have been demonstrated to explain differences in sensitivity to DLCs between sensitive and tolerant populations of Atlantic Tomcod (Microgadus tomcod) (Wirgin et al 2011).

- This was attributed to the rapid evolution of populations in highly contaminated areas of the Hudson River, resulting in a 6-base pair deletion in the AHR sequence (outside the LBD) and reduced ligand binding affinity, due to reduces AHR protein stability.

- Information is not yet available regarding whether differences in binding affinity of AhRs of fishes are predictive of differences in sensitivity of embryos, juveniles, or adults (Doering et al 2013).

Key Event Description

The AHR Receptor

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor that belongs to the basic helix-loop-helix Per-ARNT-Sim (bHLH-PAS) superfamily and consists of three domains: the DNA-binding domain (DBD), ligand binding domain (LBD) and transactivation domain (TAD)[1]. Other members of this superfamily include the AHR nuclear translocator (ARNT), which acts as a dimerization partner of the AHR [2][3]; Per, a circadian transcription factor; and Sim, the “single-minded” protein involved in neuronal development [4][5]. This group of proteins shares a highly conserved PAS domain and is involved in the detection of and adaptation to environmental change[4].

Investigations of invertebrates possessing early homologs of the AhR suggest that the AhR evolutionarily functioned in regulation of the cell cycle, cellular proliferation and differentiation, and cell-to-cell communications (Hahn et al 2002). However, critical functions in angiogenesis, regulation of the immune system, neuronal processes, metabolism, development of the heart and other organ systems, and detoxification have emerged sometime in early vertebrate evolution (Duncan et al., 1998; Emmons et al., 1999; Lahvis and Bradfield, 1998).

The molecular Initiating Event