This Key Event Relationship is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-SA license. This license allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. The license allows for commercial use. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms.

Relationship: 3391

Title

Increased E2 availability leads to Activation, ERα

Upstream event

Downstream event

Key Event Relationship Overview

AOPs Referencing Relationship

| AOP Name | Adjacency | Weight of Evidence | Quantitative Understanding | Point of Contact | Author Status | OECD Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SULT1E1 inhibition leading to uterine adenocarcinoma via increased estrogen availability at target organ level | adjacent | Martina Panzarea (send email) | Under development: Not open for comment. Do not cite | |||

| Aromatase induction leading to estrogen receptor alpha activation via increased estradiol | adjacent | Martina Panzarea (send email) | Under development: Not open for comment. Do not cite | |||

| 17β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2, inhibition leading to activation, estrogen receptor alpha | adjacent | Martina Panzarea (send email) | Under development: Not open for comment. Do not cite |

Taxonomic Applicability

Sex Applicability

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Unspecific |

Life Stage Applicability

| Term | Evidence |

|---|---|

| All life stages |

Key Event Relationship Description

Evidence Collection Strategy

Evidence Supporting this KER

Biological Plausibility

The biological plausibility of this KERs is linked to the physiological role of E2 on estrogen-responsive tissues of all mammals.

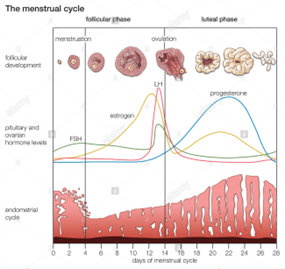

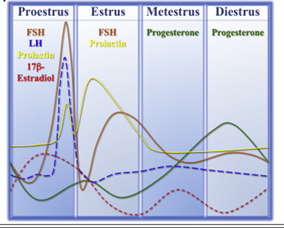

The uterus in rodents and the human undergoes cyclical changes of growth and degeneration (Fig. 10 and 11). In both species, estrogens produced from the developing follicles stimulate endometrial growth, and progesterone is responsible for converting the estrogen primed endometrium into a receptive state. In rodents, if pregnancy does not occur, dioestrus (secretory phase in humans, cycle days 15–28) terminates with regression of the corpus luteum, and the endometrium is resorbed (menstruation in humans, cycle days 1–5). During proestrus (proliferative phase in humans, cycle days 6–14) follicles develop and start to produce estrogens that stimulate endometrial growth. During oestrous (peri-ovulatory period in humans, cycle days 13–15) ovarian follicles mature. The magnitude of uterine growth stimulation is largely dependent upon the duration of bioavailable E2 and receptor interaction (Groothius et al., 2007).

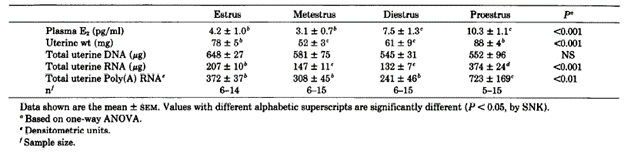

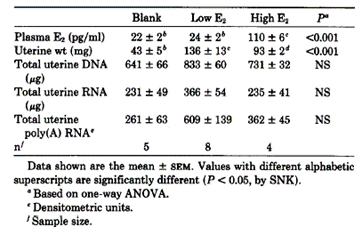

Bergman et al., 1992 studied the role of oestradiol during the mouse oestrus cycle. The study demonstrated that on proestrus, when plasma E2 levels are at the highest, the cell nuclear ER concentration in uterus was greater than metestrus. This increase was attributable to an increase in total cellular ER (cytosolic and nuclear) and secondarily to activation of ER (measured by its distribution from cytosolic to the nuclear fraction) (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4. Uterine weight, DNA, RNA, and plasma concentrations of E2 during the estrous cycle of C57BL/6J mice. from Bergman et al., 1992

Table 5. Uterine weight, DNA, RNA, and plasma concentrations of E2 in E2-treated OVX mice. from Bergman et al., 1992

Overall, this study demonstrated in mice a strong association between E2 and the biosynthesis and intracellular distribution of the uterine ER and its mRNA.

The study indicated that the basis for increased nuclear ER on proestrus involves two estrogen-dependent components: 1. activation of ER to a nucleophilic state and 2. increased concentration of ER available for activation, the latter accounting for most of the increase in nuclear ER. The process probably begins early on the day of proestrus with increased activation of ER in response to the rising levels of E2. Increased activation of ER leads to increased DNA binding of ER, which increases ER mRNA and ER. Increased ER provides the substrate for a further increase in DNA-bound ER, which serves to amplify the effect of the rising E2 in a feed-forward cascade that ultimately leads to the dramatic increases in ER mRNA, ER, and polyadenylated RNA that are observed at midday on proestrus (Bergman et al., 2005).

Empirical Evidence

The mechanism of action for E2 in uterus is well-known as well as its interaction with ER and consequent activation of the signalling cascade. One study has been included in support of the empirical evidence of the current KERs in the context of the postulated AOP.

OESTRADIOL (see Table 6)

Table 6. Empirical evidence table assembled for KER2, Oestradiol

|

Species, life-stage, sex tested |

Stressor(s) |

Upstream Effect: increased E2 availability in uterus(Y/N) |

Downstream Effect: ER activation in uterus(Y/N) |

Effect on increased E2 availability in uterus (descriptive) |

Effect on ER activation in uterus (descriptive) |

Citation |

|

C57BL/6J mice female 3-6 months old. 2 OVX |

E2 |

Y (indirect measurment) |

Y |

E2 administered in OVX mice simulated this KE. Implanted. |

Increase of nuclear ER and ER mRNA |

Bergman et al., 1992 |

OTHER Stressors

Empirical evidence may be extrapolated from different studies investigating the MoA of specific stressors; however, the KE upstream and KE downstream have never been investigated directly and together in the same experiment. The current empirical support is based on indirect evidence.

TBBPA (see Table 7)

- Sanders et al., 2016 investigated the mechanism responsible for the increased incidence of uterine lesions in TBBPA-treated rats as observed in a chronic toxicity study conducted by the National Toxicology Program (NTP). Data involving a direct evaluation of a potential increase in circulating or tissue-specific levels of oestradiol following exposure to TBBPA are not available. The authors determined that the most sensitive and efficient method to test the hypothesis that uterine lesions correlate with TBBPA-mediated disruption of estrogen homeostasis at the site-of-action was to search for TBBPA-mediated effects on genes associated with specific pathways of estrogen biosynthesis and metabolism. These changes may correlate with increased E2 or estrogen-derived reactive metabolites in the tissue; as a matter of facts, at the phenotypic level, increases in estrogen and its related signalling can cause uterine tissues to rapidly grow in size, as demonstrated by the common use of the rat uterus as a target organ for the in vivo screening of estrogen agonists and antagonists. As reported in the review by Wikoff et al.,2016 it is important to note that in the study by Sanders et al., 2016 not all gene expression changes related to estrogen signalling were increased. For example, TBBPA resulted in decreased expression of ESR2 in the proximal uterus. However, there are some lines of evidence showing that, in some instances, ESR2 may act as a repressor of ESR1 in which lower expression of ESR2 may lead to enhanced oestradiol action via increased ESR1 levels in endometrial cancer.

- Kitamura et al., 2005 investigated the effect of administered TBBPA in a uterotrophic assay. Uterine weight is a very useful index of estrogenicity (ER activation) in the immature or adult ovariectomized female rats. As a matter of facts, uterine weight (indicative of ER activation) increases many folds during proestrus under the influence of estrogen.

Table 7. Empirical evidence table assembled for KER2, TBBPA

|

Species, life-stage, sex tested |

Stressor(s) |

Upstream Effect: increased E2 availability in uterus(Y/N) |

Downstream Effect: ER activation in uterus(Y/N) |

Effect on increased E2 availability in uterus (descriptive) |

Effect on ER activation in uterus (descriptive) |

Citation |

|

|

In vivo |

|||||||

|

Wistar Han rats, circa 9 wks old, female |

TBBPA |

Y (indirect measurement) |

Y (indirect measurement) |

↑ of estrogen stimulated genes in proximal (near the cervix) and distal section (near the ovaries) of uterus (e.g., Thra, esr1, Ppara, Igf1, Cyp1b1, Ugt1a1), Ccnd2 in distal uterus Changes observed for ESR2, ttr in proximal uterus, Thrb in distal uterus, glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in proximal uterus ↓ Cyp11a1 in uterus, Hsd17B2 in distal uterus 250 mg/kg bw per day after 5 days of exposure |

↑ of estrogen stimulated genes in proximal (near the cervix) and distal section (near the ovaries) of uterus (e.g., Thra, esr1, Ppara, Igf1, Cyp1b1, Ugt1a1), Ccnd2 in distal uterus Changes observed for ESR2, ttr in proximal uterus, Thrb in distal uterus, glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in proximal uterus ↓ Cyp11a1 in uterus, Hsd17B2 in distal uterus 250 mg/kg bw per day after 5 days of exposure |

Sanders et al., 2016 |

|

|

B6C3F1 mice (ovariectomized), 8 wks old, female |

TBBPA |

Y (indirect measurement) |

Y (indirect measurement) |

↑ uterus/body weight in vivo with weak activity on ERE luciferase assay indicative that the substance does not bind directly to the ER 20 mg/kg bw per day after 3 days of exposure |

↑ uterus/body weight in vivo with weak activity on ERE luciferase assay indicative that the substance does not bind directly to the ER 20 mg/kg bw per day after 3 days of exposure |

Kitamura et al., 2005 |

|

Triclosan (see Table 8)

- Jung et al., 2012; modulation of complement 3 (C3) mRNA in uterus is demonstrated to be an estrogen sensitive marker. Triclosan was found to up-regulate the expression of such gene. The mRNA expression is blocked by the steroid antagonists ICI and RU

- Jung et al., 2012; Uterotrophic assay. Triclosan was found to induce uterine weight. The increase uterine is reversed by the treatment with steroid antagonists ICI and RU

- Jung et al., 2012; Calbindin-D9k (CaBP-9k) has been shown to be a novel biomarker for detecting endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs). The CaBP-9k is an intracellular calcium binding protein and may increase calcium ion (Ca2+) absorption by buffering Ca2+ in the intestine. CaBP-9k has two calcium-binding domains that interact with Ca2+ with high affinity in the cytoplasm. The CaBP-9k gene is expressed in various tissues, including intestine, kidney, uterus, placenta, pituitary gland, and bone. The expression of the CaBP-9k gene in uterus is up-regulated by estrogen and down-regulated by progesterone (P4) during the oestrous cycle and during early pregnancy in the rat uterus. In the study by Jung et al., 2012 TCS effects on the induction of CaBP-9k mRNA and protein expression were examined by real-time PCR and Western blot analysis in the uteri of immature rats and in GH3 cells. In addition, the steroid antagonists, ICI 182,780 (ICI) and RU 486 (RU), were used to examine the involvement of E2 receptor and/or P4 receptor to verify endocrine effects of TCS. The antimicrobial agent Triclosan was found to up-regulate the expression of uterine CaBP-9k.

- Stoker et al., 2010; the present study demonstrates that Triclosan alters female postnatal reproductive development and uterine response to exogenous estrogen in the developing female rat. These responses suggest that Triclosan augments estrogen action and that there is the potential for Triclosan to alter estrogen-dependent function.

Table 8. Empirical evidence table assembled for KER2, Triclosan

|

Species, life-stage, sex tested |

Stressor(s) |

Upstream Effect: increased E2 availability in uterus(Y/N) |

Downstream Effect: ER activation in uterus(Y/N) |

Effect on increased E2 availability in uterus (descriptive) |

Effect on ER activation in uterus (descriptive) |

Citation |

|

In vivo |

||||||

|

Sprague-Dawley rats, immature |

Triclosan |

Y (indirect measurement) |

Y (indirect measurement) |

The antimicrobial agent Triclosan was found to up-regulate the expression of uterine CaBP-9k. Triclosan was found to up-regulate the expression of mRNA C3 in uterus. 37.5 mg/kg bw per day after 3 days of exposure Increased uterus weight/bw ratio in TCS rats treated compared to vehicle. 7.5 mg/kg bw per day after 3 days of exposure

|

The antimicrobial agent Triclosan was found to up-regulate the expression of uterine CaBP-9k. Triclosan was found to up-regulate the expression of mRNA C3 in uterus. 37.5 mg/kg bw per day after 3 days of exposure Increased uterus weight/bw ratio in TCS rats treated compared to vehicle. 7.5 mg/kg bw per day after 3 days of exposure |

Jung et al., 2012 |

|

Female, Wistar rats, PND19 |

Triclosan |

N (indirect measurement) |

N (indirect measurement) |

No effect in a uterotrophic assay. The increase uterine weight/bw ratio was observed only in co-treatment with ethylinoestradiol |

No effect in a uterotrophic assay. The increase uterine weight/bw ratio was observed only in co-treatment with ethylinoestradiol |

Stoker et al., 2010 |

|

Female, Wistar rats, PND22 |

Triclosan |

Y (indirect measurement) |

Y (indirect measurement) |

Female pubertal assay: increase blotted and wet uterine absolute and relative weights at PND 42 at 150 mkd . This picture could be indicative of an estrogenic condition at uterine level but it is not informative on the MoA. 150 mg/kg bw per day after 21 days of exposure |

Female pubertal assay: increase blotted and wet uterine absolute and relative weights at PND 42 at 150 mkd . This picture could be indicative of an estrogenic condition at uterine level but it is not informative on the MoA. 150 mg/kg bw per day after 21 days of exposure |

Stoker et al., 2010 |

|

Female, Wistar rats, PND18 |

Triclosan |

N (indirect measurement) |

N (indirect measurement) |

No effect in a uterotrophic assay. Doses 0, 0.8, 2.4, 8.0 mg/kg bw per day |

No effect in a uterotrophic assay. Doses 0, 0.8, 2.4, 8.0 mg/kg bw per day |

Montagnini et al., 2018 |

|

Female, Wistar rats, PND21 |

Triclosan |

N (indirect measurement) |

N (indirect measurement) |

No effect in a uterotrophic assay. Doses 0, 1, 10, 50 mg/kg bw per day |

No effect in a uterotrophic assay. Doses 0, 1, 10, 50 mg/kg bw per day |

Rodriguez-Sanchez 2010 |

|

Wistar rats (Charles River) PND 13 |

Triclosan |

N (indirect measurement) |

N (indirect measurement) |

No effect in a uterotrophic assay. |

No effect in a uterotrophic assay. |

Louis et al., 2013 |

Parabens (i.e., Methylparabens/Ethylparabens) (see Table 9)

Sun et al., 2016: In this study, the uterotrophic activities of methylparaben (MP) and ethylparaben (EP) at doses close to the acceptable daily intake as allocated by JECFA were demonstrated in immature Sprague-Dawley rats by intragastric administration, and up-regulations of estrogen-responsive biomarker genes were found in uteri of the rats by quantitative real-time RT–PCR (Q-RT-PCR).

Table 9. Empirical evidence table assembled for KER2, Parabens

|

Species, life-stage, sex tested |

Stressor(s) |

Upstream Effect: increased E2 availability in uterus(Y/N) |

Downstream Effect: ER activation in uterus(Y/N) |

Effect on increased E2 availability in uterus (descriptive) |

Effect on ER activation in uterus (descriptive) |

Citation |

|

In vivo |

||||||

|

Sprague-Dawley rats, female, PND20 |

Parabens * |

Y |

Y |

↑ expression of estrogen-responsive genes (i.e., icabp, CaBP-9k, itmap1, pgr) Starting from 4 mg/kg bw per day after 3 days of exposure ↑ Uterus weight Starting from 20 mg/kg bw per day after 3 days of exposure |

↑ expression of estrogen-responsive genes (i.e., icabp, CaBP-9k, itmap1, pgr) Starting from 4 mg/kg bw per day after 3 days of exposure ↑ Uterus weight Starting from 20 mg/kg bw per day after 3 days of exposure |

Sun et al., 2016 |

* Methylparaben, Ethylparaben.

Dose and temporal concordance

In accordance with the OECD handbook for the AOP developers this section should include the extent of the evidence that KE upstream is generally impacted at doses (or stressor severities) equal to or less than those at which KE downstream is impacted. In the case of the current KER the evidence is poor, and many inconsistencies were identified.

The dose and temporal concordance tables for stressors TBBPA, Triclosan and Parabens were included in Annex A.3 of the Scientific Opinion.

Uncertainties and Inconsistencies

- E2 availability in uterus is rarely measured as stand-alone endpoint. The evidence collected on different stressors indicates the induction of specific estrogen-responsive genes; however, there is still little knowledge in this field

- There are few studies indicating which genes can be used as biomarkers indicative of an increase of E2 availability in uterus / ER activation in uterus.

- It is well-known that there is large variability in the uterotrophic assay (Brown et al., 2015), this can be explained by the differences in the experimental design

- The presence of phytoestrogen in the diet could influence the outcome of the experiments

Known modulating factors

It is acknowledged that the increase of oestradiol (E2) content in malignant endometrium compared to macroscopically normal looking endometrium supports the idea of an important role of excessive estrogenic stimulation in the development and further progression of endometrial cancer in endometrial cancer.

However, further investigation on the impact of these modulation factors on quantitative aspects of the response-response function that describe the relationships between KEs should be performed

Quantitative Understanding of the Linkage

Response-response Relationship

In AOP504, there is only one study where the increase of E2 bioavailability in uterus and ER activation has been measured in the same experiment in vivo (Bergman et al., 1992). Therefore, there are not enough data available to make any definitive quantitative correlations.

Time-scale

Known Feedforward/Feedback loops influencing this KER

Domain of Applicability

References

Bergman MD, Schachter BS, Karelus K, Combatsiaris EP, Garcia T and Nelson JF, 1992. Up-regulation of the uterine estrogen receptor and its messenger ribonucleic acid during the mouse estrous cycle: the role of estradiol. Endocrinology, 130:1923-1930. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.4.1547720

Jung EM, An BS, Choi KC and Jeung EB, 2012. Potential estrogenic activity of Triclosan in the uterus of immature rats and rat pituitary GH3 cells. Toxicol Lett, 208:142-148. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.10.017

Kitamura S, Suzuki T, Sanoh S, Kohta R, Jinno N, Sugihara K, Yoshihara Si, Fujimoto N, Watanabe H and Ohta S, 2005. Comparative Study of the Endocrine-Disrupting Activity of Bisphenol A and 19 Related Compounds. Toxicological Sciences, 84:249-259. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi074

Louis GW, Hallinger DR and Stoker TE, 2013. The effect of Triclosan on the uterotrophic response to extended doses of ethinyl estradiol in the weanling rat. Reprod Toxicol, 36:71-77. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.12.001

Montagnini BG, Pernoncine KV, Borges LI, Costa NO, Moreira EG, Anselmo-Franci JA, Kiss ACI and Gerardin DCC, 2018. Investigation of the potential effects of Triclosan as an endocrine disruptor in female rats: Uterotrophic assay and two-generation study. Toxicology, 410:152-165. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2018.10.005

Rodríguez PE and Sanchez MS, 2010. Maternal exposure to Triclosan impairs thyroid homeostasis and female pubertal development in Wistar rat offspring. J Toxicol Environ Health A, 73:1678-1688. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2010.516241

Sanders JM, Coulter SJ, Knudsen GA, Dunnick JK, Kissling GE and Birnbaum LS, 2016. Disruption of estrogen homeostasis as a mechanism for uterine toxicity in Wistar Han rats treated with tetrabromobisphenol A. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 298:31-39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2016.03.007

Stoker TE, Gibson EK and Zorrilla LM, 2010. Triclosan exposure modulates estrogen-dependent responses in the female wistar rat. Toxicol Sci, 117:45-53. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq180

Sun L, Yu T, Guo J, Zhang Z, Hu Y, Xiao X, Sun Y, Xiao H, Li J, Zhu D, Sai L and Li J, 2016. The estrogenicity of methylparaben and ethylparaben at doses close to the acceptable daily intake in immature Sprague-Dawley rats. Sci Rep, 6:25173. doi: 10.1038/srep25173

Wikoff DS, Rager JE, Haws LC and Borghoff SJ, 2016. A high dose mode of action for tetrabromobisphenol A-induced uterine adenocarcinomas in Wistar Han rats: A critical evaluation of key events in an adverse outcome pathway framework. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol, 77:143-159. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2016.01.018