This AOP is licensed under the BY-SA license. This license allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. The license allows for commercial use. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms.

AOP: 593

Title

Redox cycling of a chemical by mitochondria leads to degeneration of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons

Short name

Graphical Representation

Point of Contact

Contributors

- Stefan Schildknecht

- Giacomo Grumelli

- Barbara Viviani

Coaches

OECD Information Table

| OECD Project # | OECD Status | Reviewer's Reports | Journal-format Article | OECD iLibrary Published Version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

This AOP was last modified on October 03, 2025 14:31

Revision dates for related pages

| Page | Revision Date/Time |

|---|---|

| Redox cycling of a chemical by mitochondria | October 03, 2025 10:37 |

| Elevated mitochondrial ROS and dysfunction | October 03, 2025 11:24 |

| Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway | October 01, 2025 07:04 |

| Parkinsonian motor deficits | March 12, 2018 12:44 |

| Proteostasis, impaired | October 16, 2025 02:38 |

| Redox cycling leads to Mito ROS dysfunction | October 03, 2025 13:31 |

| Mito ROS dysfunction leads to Proteostasis, impaired | October 03, 2025 14:03 |

| Proteostasis, impaired leads to Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway | October 03, 2025 04:34 |

| Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway leads to Parkinsonian motor deficits | October 03, 2025 18:38 |

| Paraquat | November 29, 2016 18:42 |

Abstract

This Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) describes the linkage between excessive ROS production at the level of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and parkinsonian motor deficits, including Parkinson’s disease (PD). Interaction of a compound with complex I and/or III of the mitochondrial respiratory chain has been defined as the molecular initiating event (MIE) that triggers mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired proteostasis, which then cause degeneration of dopaminergic (DA) neurons of the nigra-striatal pathway. These causatively linked cellular key events result in motor deficit symptoms, typical of parkinsonian disorders including PD, described in this AOP as an Adverse Outcome (AO). This AOP also includes neuroinflammation as a KE and is intending the KER with degeneration of dopaminergic neurons as a causative link but the priority of the temporal sequence is not defined as neurodegeneration can be the cause as well the consequence of the KE neuroinflammation. Since the role DA neurons of the Substantia Nigra pars compacta (SNpc) projecting into the striatum is essential for motor control, the key events refer to these two brain structures, i.e. SNpc and striatum. The weight-of-evidence supporting the relationship between the described key events is mainly based on effects observed after an exposure to the well-known pesticide paraquat which will be used as a tool chemical to support this AOP.

AOP Development Strategy

Context

Evidence from literature consistently indicates that a relationship exists between pesticide exposure and the onset of parkinsonian motor deficit (Ntzani et al., 2013, EFSA 2017). In 2017, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) started a project to provide a theoretical basis explaining the link between redox cycler and degeneration of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons leading to parkinsonian motor deficits (EFSA 2017). This project resulted in an AOP converging on the OECD-endorsed AOP 3 which describes the sequence of events from mitochondrial complex I inhibition to parkinsonian motor deficits. In the effort to develop an AOP network addressing parkinsonian motor deficits involving multiple MIEs, this AOP has been refined and updated based on recent scientific evidence.

Strategy

As an initial step in constructing AOPs relevant to Parkinson’s disease (PD), the process was guided by the scientific consensus that mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress play a critical role in the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc), and that the loss of these neurons underlies the manifestation of parkinsonian motor symptoms. Based on this established knowledge, an initial conceptual framework was developed. For well-characterized KEs, evidence was obtained from seminal publications recommended by domain experts and supported with expert judgment. Empirical evidence for the KERs was provided using prototypical stressors identified from the literature, initially the herbicide paraquat, which is supported by epidemiological evidence and experimental data. In the updated version, additional redox cyclers were incorporated to identify further relevant studies through a stressor-based approach.

Summary of the AOP

Events:

Molecular Initiating Events (MIE)

Key Events (KE)

Adverse Outcomes (AO)

| Type | Event ID | Title | Short name |

|---|

| MIE | 2362 | Redox cycling of a chemical by mitochondria | Redox cycling |

| KE | 2363 | Elevated mitochondrial ROS and dysfunction | Mito ROS dysfunction |

| KE | 889 | Proteostasis, impaired | Proteostasis, impaired |

| KE | 890 | Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway | Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway |

| AO | 896 | Parkinsonian motor deficits | Parkinsonian motor deficits |

Relationships Between Two Key Events (Including MIEs and AOs)

| Title | Adjacency | Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|

Network View

Prototypical Stressors

| Name |

|---|

| Paraquat |

Life Stage Applicability

| Life stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Adult | High |

Taxonomic Applicability

Sex Applicability

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

| Female | High |

Overall Assessment of the AOP

Domain of Applicability

This proposed AOP is neither sex-dependent nor associated with certain life stage; however, male aged animals are considered more sensitive. The relevance of this AOP during the developmental period has not been investigated. In vivo testing has no species restriction. However, host susceptibility is likely to have a relevant impact on the outcome of the studies and in this context, elements of stress and animal strain could have a profound impact on the outcome of the studies (Youdim et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005; Yin et al., 2011; Jiao et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2014). The mouse was the species most commonly used in the experimental models conducted with the chemical stressor paraquat and the C57BL/6J is considered the most sensitive mouse strain (Jiao et al., 2012; Smeyne et al., 2016). However, animal models (rodents in particular) would have limitations as they are poorly representative of the long human lifetime as well as of the human long-time exposure to the potential toxicants. Human cell-based models would likely have better predictivity for humans than animal cell models if biologically relevant by means of being able of recapitulate the key events in the toxicology and pathology pathway providing robust and repeatable results predictive of the chemical concentration that lead to a particular outcome. In this case, toxicokinetics information from in-vivo studies would be essential to test the respective concentrations in-vitro on human cells.

Essentiality of the Key Events

Direct essentiality evidence is coming from experiments conducted with antioxidant agents or following manipulation of the biological systems protecting from or regulating ROS production and oxidative stress. Manifestation of motor symptoms differs in rodents and human and for this reason their value should depend upon its relationship to striatal dopaminergic function. Study designed to demonstrate recovery of clinical signs following DA replacement are limited with the chemical tool paraquat. Evidence of essentiality is however provided following unilateral intranigral injection of paraquat or in drosophila models. The overall WoE for the essentiality is strong.

Table 1 - Essentiality of the KE; WoE analysis

| Support for essentiality of KEs | Are downstream KEs and/or the AO prevented if an upstream KE is blocked? | Strong: Direct evidence from specifically designed experimental studies illustrating essentiality for at least one of the important KEs (e.g. stop/ reversibility studies, antagonism, knock out models, etc.) | Moderate: Indirect evidence that sufficient modification of an expected modulating factor attenuates or augments a KE leading to increase in KEdown or AO | Weak: No or contradictory experimental evidence of the essentiality of any of the KEs |

| MIE - Redox Cycling of a chemical by mitochondrial | Strong | Overexpressing enzymes involved in O2 dismutation speci!cally located at the mitochondria prevents neuronal cell death in vitro (Rodriguez-Rocha et al., 2013; Filograna et al., 2016). Accordingly, depletion of mitochondrial SOD2 exacerbate PQ-toxicity in Drosophila (Kirby et al., 2002), while mitochondrial enzymes activity is restored and neuronal death in cortex reduced in SOD2 knock out animals treated with antioxidants (Hinerfeld et al., 2004). Mitochondrial aconitase knock down attenuated PQ induced H2O2 production and respiratory capacity de!ciency in neuronal cells (Cantu, 2011) | ||

| KE1 - Elevated mitochondrial ROS, dysfunction | Strong | In vitro, PQ toxicity both in terms of ROS production, mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal death is rescued by several antioxidants (Hinerfeld et al., 2004; McCarthy et al., 2004; Peng et al. 2005; Chau et al., 2009, 2010; de Oliveira, 2016). Most of these drugs, like synthetic superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics or SOD-fusion proteins also protect against PQ-induced oxidative damage and/or DA neurons degeneration in vivo (Hinerfeld et al., 2004; Peng et al., 2005; Choi, 2006) improving motor skills (Somayajulu-Nitu et al., 2009; Muthukumaran et al., 2014). Overexpression of antioxidant enzymes speci!cally at the mitochondria protects Drosophila and yeast from PQ-toxicity at low doses (Mockett et al., 2003; Tien Nguyen-nhu and Knoops, 2003). On the other hand, depletion of antioxidant systems exacerbates PQ toxicity both in vitro and in vivo (Van Remmen et al., 2004; Lopert et al., 2012; Liang et al., 2013). USP30, a deubiquitinase localised to mitochondria, antagonises mitophagy. Overexpression of USP30 removes ubiquitin in damaged mitochondria and blocks mitophagy. Reducing USP30 activity enhances mitochondrial degradation in neurons. Knockdown of USP30 in dopaminergic neurons protects "ies against paraquat toxicity in vivo, ameliorating defects in dopamine levels, motor function and organismal survival in Drosophila (Bingol et al., 2014). More in general, overexpression of Sods in DA neurons counteracts PQ-induced oxidative damage and reduces motor dysfunction in Drosophila (Filograna et al., 2016). Similarly, the use of antioxidants also restores PQ-induced motor activity in Drosophila (Jimenez-Del-Rio et al., 2010) | ||

| KE2 - Impaired, proteostasis | Moderate | Most of the experimental evidence supporting the essentiality is coming from experiments conducted in transgenic animals or studies conducted with the chemical stressor Rotenone and MPTP, known chemical toxins used to mimic PD (Dauer et al., 2002; Kirk, 2002, 2003; Klein, 2002; Lo Bianco, 2002; Lauwers, 2003; Fornai et al., 2005) Exposure to the chemical stressor paraquat of mice with inducible overexpression of familial PD-linked mutant a-syn in dopaminergic neurons of the olfactory bulb exacerbate the increase of soluble and insoluble a-syn expression, accumulation of a-syn at the dendritic terminals, reduction of autolysosomial clearance, mitochondrial condensation and damage. None of these effects occurs in PQ-treated mice with suppressed a-syn expression. Loss of DA neurons in the olfactory bulb is evident in PQ-treated mutant mice but not in both PQ-treated mice with suppressed a-syn expression (after doxycycline administration) and untreated mutant mice (Nuber et al., 2014) In vitro system overexpressing the neuroprotective molecular chaperone human DJ-1, showed more resistance to the proteasome impairment induced by paraquat. Similarly, preservation was observed in the same system following treatment with a known proteasome inhibitors (epoxomycin) (Ding and Keller, 2001). However, although evidence exists to support some essentiality of impaired proteostasis, a single molecular chain of events cannot be established | ||

| KE3 -Degeneration of DA neurons of nigrostriatal pathway | Strong | Clinical and experimental evidences show that the pharmacological replacement of the DA neurofunction by allografting fetal ventral mesencephalic tissues is successfully replacing degenerated DA neurons resulting in the total reversibility of motor deficits in an animal model and a partial effect is observed in human PD patients (Freed et al., 1990; Henderson et al., 1991; L!opez-Lozano et al., 1991; Spencer et al., 1992; Widner et al., 1992; Peschanski et al., 1994; Han et al., 2015). Concomitant administration of selective type B monoamine oxidase inhibitor slowed the progression parkinsonian motor symptoms induced by unilateral intranigral injection of paraquat which is expected to induce approximately 90% of neuronal loss. It provides a protective effect on the moderate injury elicited by PQ toxicity. A post-treatment administration of apomrphine, a DA agonist, induced controlateral circling behaviour which correlated well with the decrease of striatal DA (Liou, 1996, 2001). However, for most of the experiments conducted with paraquat, the amount of DA neuronal cell loss and drop in striatal DA was not consistent or below the threshold for triggering motor symptoms. In addition, studies showing an altered behaviour resulting from striatal drop in DA, lack a DA replacement strategy | ||

Evidence Assessment

Response–response and incidence concordance

Toxicity mediated by redox cycling is based on acceptance of an electron by a chemical from a reductant, formation of a radical, and transfer of an electron to molecular oxygen. The process is leading to the generation of superoxide and mitochondria are one of the presumed sites where the chemical is initially reduced within the cell to form superoxide. This is the chemical based mechanism of action of the herbicide paraquat (PQ), which is therefore considered a suitable chemical tool/ stressor for exploring the link between the MIE and the AO. In animal models, PQ susceptibility is known to act synergistically with microglia leading to its activation (Purisai et al., 2007; Mitra et al., 2011). Microglia through plasma-membrane NADPH-oxidase may also activate the extracellular redox cycling of PQ favouring its transport within dopaminergic neurons (Rappold et al., 2011). The kinetic and metabolism of PQ is complex and the amount of PQ entering and accumulating into the brain is dependent on dose, route of administration, expression of transporters, animal age and strain. Multiple genetic factors are also involved in host susceptibility which is likely to represent an important source of variability (Corasaniti et al., 1991; Youdim, 2003; Li et al., 2005; Tieu, 2011; Yin et al., 2011; Jiao et al., 2012). These elements are the possible/likely reason of lack of reproducibility of apical endpoints as observed in some studies conducted with this stressor (Breckenridge et al., 2013; Smyne et al., 2016). In-vivo, the commonly used dose of 10 mg/kg administered i.p. leads to a brain concentration of around 3 uM after 6 doses (Prasad et al., 2009; Smeyne et al., 2016) and around 6–10 uM in striatum after 24 doses (Prasad et al., 2009). A single s.c. administration of 10 mg/kg leads to 3.88 + 0.79 lM serum concentration after 3 h reaching 0.36 + 0.09 uM in the extracellular space of the striatum (Shimizu et al., 2001). At this dose level (10 mg/kg i.p.), ambiguous results in terms of neuronal loss and occurrence of parkinsonian motor symptoms are reported in C57BL/6J mice (Thiruchelvam et al., 2000b; McCormack et al., 2002; Barlow et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005, 2012; Khwaja et al., 2007; Prasad et al., 2007, 2009; Fei et al., 2008; Cristovao et al., 2009; Fernagut et al., 2009; Mangano et al., 2009, 2011, 2012; Breckenridge et al., 2013; Watson, 2013; Minnema, 2014; Smeyne et al., 2016). In order to integrate data on paraquat toxicity from widely different experimental models, ranging from cell cultures to repeat dose animal studies, the concentrations close to the target site were compared by classical approaches of in vitro in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) based on the available publications. The lowest observed effect concentrations in vitro were in the range of 20 uM. Concentrations up to 200 uM have been used for some studies. A variability of observed concentrations is expected from the fact that PQ needs a transporter to cross cell membranes, and that different oxidation states of PQ have different affinities for transporters (Rappold et al., 2011). Thus, the levels of transporter expression, the presence of microglia and the oxidation state of PQ determine its intracellular concentration. This may explain variations of effective in vitro concentrations by at least 10-fold. For the in vivo situation, different sets of data are available to estimate the PQ concentration in DA neurons. A study on average brain concentrations after 6 doses found an average brain concentration of 0.54 lg/g brain tissue, corresponding to an average brain tissue concentration of 3 lM (Smeyne et al., 2016). It needs to be assumed that some cells accumulate PQ, while others do not. Thus, intracellular concentrations in DA neurons may be considerably higher than 3 uM, considering the uptake of PQ. In another study, plasma concentrations and extracellular brain concentrations were measured 3 h after a single dose. Extracellular concentrations of 0.4 uM were reached in the brain (Shimizu et al., 2001). It needs to be assumed that this would be higher after multiple dosing. Indeed a study by Prasad et al., 2009 showed that the extracellular concentration in the striatum was around 3.3 uM after 6 doses and around 10 uM after 24 doses of 10 mg/kg i.p.

These data suggest that the brain concentration at the target site (inside DA neurons) is in the 1–2 digit uM range. This range overlaps well with the effective in vitro concentrations of 20–50 uM. Within the limits of accuracy possible (the intracellular concentrations have not been measured within DA neurons) this IVIVE shows that in vitro and in vivo active concentrations are within the same order of magnitude and thus aligned. In a conservative approach, the range of brain concentration expected to represent the steady state (3–10 uM) of PQ can be considered only indicative and will be used in this AOP to define a possible probabilistic threshold of activation of the MIE leading to the AO. With the limited number of doses known from in-vivo studies, an intra (in the same) and inter (between) KE response–response relationship can be observed. A response–response relationship in the increase in activity of ROS scavenging enzymes can be observed (KE 1) in-vivo; however, the KE degeneration of dopaminergic neurons and the AO can only be seen at the threshold concentration in the brain of about 3–10 uM reached after repeated exposure to PQ 10 mg/kg bw, and not for higher doses due to the marked general toxicity (Mitra et al., 2011). The frequency of the KE degeneration of dopaminergic neurons and the AO were less than for the other key events. In this AOP, neuroinflammation was considered to have a direct effect on paraquat activation and on loss of DA neurons (Purisai et al., 2007; Rappold et al., 2011).

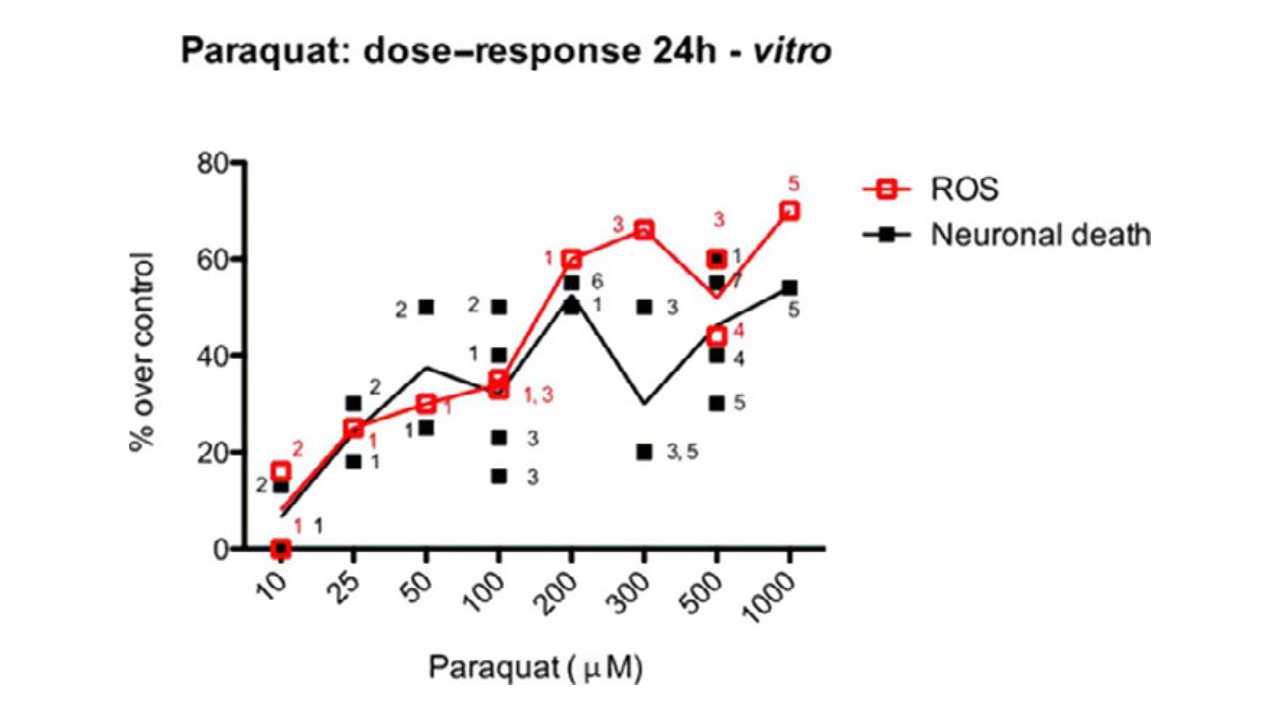

In vitro, an intra KEs response–response is evident, with some evidences of inter KEs response– response concordance. However, when multiple time of sampling are applied to the experimental design, the inter KEs response–response concordance is stronger. In-vitro, a strong response–response concordance between KE1 and cell death (KE 3) is evident (Figure 1). Overall, the response–response and incidence concordance was considered moderate.

Figure 1: PQ-induced ROS and Cell death (% over controls) at 24 h in neuronal cells. Points in the figure derive from the listed papers, targeted by the number associated to each symbol (1-de Oliveira 2016, 2-Gonz!alez-Polo 2007, 3-Lopert 2012, 4-Rodriguez-Rocha 2013, 5-Huang 2012, 6-Ding 2001, 7-Yang and Tiffany Castiglioni 2007) Data refers to different neuronal cell lines and primary cultures, and to different methods of detection. As such, single results have been calculated over their control to allow comparison between different studies.

Temporal concordance across the AOP

There is a strong agreement on the sequence of pathological events linking the MIE to the adverse outcome (Fujita et al., 2014). The temporal concordance is strong when considering the chronicity and progressive nature of the pathology of parkinsonian disorders. Temporal concordance among the KE 1, 2, 3 and AO can be observed in the experimental models of PD using the chemical stressors rotenone and MPTP (Betarbet, 2000, 2006; Sherer et al., 2003, Fornai et al., 2005) which are sharing the same KEs with this AOP but are caused by a different MIE. With the chemical stressor MPTP, to trigger the KE3 (i.e. degeneration of DA neurons in SNpc with presence of intracytoplasmic Lewy-like bodies) and motor de!cits (AO), proteostasis needs to be disturbed for a minimum period of time (Fornai et al., 2005) and this is similarly expected with chemicals inducing redox cycling like PQ (Ossowska et al., 2005). In vivo, with the chemical stressor PQ, evidence of temporal concordance is limited by the study design using single time-point descriptive assessment. In vitro, evidence of temporal concordance is limited by the fact that 24 and 48 h were the most investigated time points. Nevertheless, those papers taking into account shorter time points show that a good temporal concordance exist between MIE (4 h), KE2 (6 h) and KE3 (12–24 h) (Ding, 2001; Gonzalez-Polo, 2007; Cantu, 2011; de Oliveira, 2016). Based on the established knowledge on chronicity and progression of parkinsonian disorders, the temporal concordance is considered strong for this AOP up to the KE 3 (degeneration of DA neurons of nigrostriatal pathway). The occurrence of the AO outcome is strongly linked to the amount of DA in the striatum and to the loss of DA neurons in the SNpc. Following treatment with the chemical stressor/s the key events are observed in the proposed order in this AOP.

Table 2 - Response–Response and temporality concordance table in vitro

| Concentration at the target site, in-vitro | MIE | KE1 - Elevetad mitochondrial ROS, dysfunction | KE2 - Impaired, proteostasis | KE3- Degeneration of DA neurons of nigrostriatal pathway |

| 10 uM [1, 10, 12] | no data | +(at 24 h) | + (ALP 6 h, time- dependent at 24 h) | +(at 24 h) |

| 20 10 to 50 uM [1, 2, 10] | no data | + (at 6 and 24 h; ne 3 h) | + (UPS at 6 h) | +(at 24 h) |

| 50–200 uM [1, 2, 8, 10, 13] | ++ (at 24 and 48 h) | ++ (at 6 and 24 h) | ++ (UPS at 6 h) | ++ (at 24 and 48 h) |

| 200 uM to 1 mM [3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12] | +++ (at 4, 6, 24 and 48 h) | ++ (at 4 and 6 h) +++ (at 24 h) | +++ (UPS at 48 h) ++ (ALP at 24 h) | ++/+++ (at 18, 24 and 48 h) |

Table 3 - Response–Response and temporality concordance table in vivo

| Concentration at the target site, in-vivo | MIE | KE1 - Elevetad mitochondrial ROS, dysfunction | KE2 - Impaired, proteostasis | KE3- Degeneration of DA neurons of nigrostriatal pathway | AO - Parkinsonian motor symptoms |

| Below 3 uM [15, 16] | + (4 weeks) | Increase activity in ROS scavenging enzymes + (4 week) | No data | Decrease in number of TH+ in SN + (at 4 week) | No locomotor deficit |

| About 3–10 uM [6,5, 13,14, 15] | ++ | Increased lipid peroxidation - (1 week) ++/+++ (2 week) +++ (6–9 week) Increase activity in ROSscavenging enzymes (4 week) ++ | Impaired proteostasis and autophagy ++ | Decrease in number of TH+ in SN - (1 week) + (at 2–4 week) | Locomotor deficit +(at 2–4 week) |

Gonzalez-Polo 2007 [1]; Ding and Keller, 2001 [2]; Yang and Tiffany-Castiglioni, 2007 [3]; Cantu 2011 [4]; Breckenridge 2013 [5]; Prasad 2007 and 2009 [6]; Huang 2012 [7]; Lopert 2012 [8], *LDH as % of control and not of maximal release; Chau 2009 [9]; de Oliveira 2016 [10]; Garcia-Garcia 2013 [11]; Rodriguez-Rocha 2013 [12]; Patel 2006 [13]; McCormack 2005 [14]; Mitra et al. 2011 [15]; Brooks et al. 1999 [16]. +, ++, +++ are intended only to demonstrate intra and inter KEs relationship.

Strength, reproducibility of the experimental evidence, and specificity of association of AO and MIE

There is a strong agreement that ROS production and mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to neurodegeneration and motor symptoms of parkinsonian disorders and familial PD genes are also implicated in ROS production by mitochondria (Gandhi et al., 2009; Yao et al., 2011; Sanders et al., 2013; Fujita et al., 2014). The chemical stressor used for the empirical support, PQ, is a well-known substance with a toxicity primarily mediated by redox cycling (Day et al., 1999; Tieu, 2011). With PQ, ROS production and oxidative stress, impaired proteostasis, and loss of nigral dopaminergic neurons are reported (Brooks et al., 1999; McCormack et al., 2002; Mitra et al., 2011; Su et al., 2015). Some uncertainties on the initial mitochondrial involvement in triggering PQ redox-cycle in vivo exists due to the prolonged (consistent with a generalised oxidative stress) and repeated exposure and the use of general indicators of oxidative stress like lipid and protein oxidation. Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons (KE3) was tested in-vivo in many studies conducted in rat and mice with an higher prevalence of testing in mice. The estimated mean number of TH+ neurons in the SNpc or TH+ axons and terminals in the striatum was the common endpoint measured, with detailed neuropathology, neurochemistry and behavioural evaluation conducted more seldomly. Reproducibility of the effect of PQ on these parameters in mice was questioned by some authors (Thiruchelvam et al., 2000b; Cicchetti et al., 2005; Breckenridge et al., 2013; Minnema et al., 2014; Smeyne et al., 2016). For studies conducted in mice, a systematic review of the published literature that has evaluated the effects of PQ on the SNpc and striatum was included in Smeyne et al. (2016). The potential impact of animal, dose variables, stereological and methodological factors was evaluated. Despite the thorough evaluation conducted and the identi!cation of some methodological biases potentially affecting a number of studies, a signi!cant controversy remains regarding the reproducibility of the finding using PQ as a chemical stressor and a clear methodological bias affecting it cannot be fully established. In addition in a number of studies performed with the chemical stressor PQ, loss of dopaminergic neurons (KE3)was not associated with an effect on striatal dopamine levels (Thiruchelvam et al., 2000b; McCormack et al., 2002). Although this can be due to the activation of compensatory effects or compensatory upregulation of TH activity in the striatum following PQ treatment (Thiruchelvam et al., 2000b; McCormack et al., 2002; Ossowska et al., 2005), this effect is known to be quantitatively linked to the loss of DA neurons and a threshold is likely to exists. The role and in"uence of the animal species, strain, age, route of administration, dose scheduling and susceptibility of neuronal population to the noxa on the outcome of the studies cannot be completely ruled out. The occurrence of parkinsonian motor symptoms was not consistently reported for the chemical stressor PQ. Evidence on the occurrence of the AO can however be observed with PQ following unilateral intranigral administration where loss of neuronal cells was marked (ca. 90%). For most of the studies conducted with the tool chemical PQ administered by i.p. the amount of DA neuronal loss was relatively limited (e.g. 20–30%) and the AO i.e. parkinsonian motor symptoms, was therefore not consistently reported. These observations are in line with the human evidence that parkinsonian motor symptoms are only evident in PD when striatal DA drops approximately 80% (corresponding to a 60% DA neuronal cells loss (Jellinger et al., 2009). Indeed, the variability observed in the latest KE and in the AO, not clearly associated with methodological biases in some cases, could be well reflecting the variability in host susceptibility. This is particularly true when considering the complexity of the factors influencing the local disposition i.e. concentration at the target site of the chemical stressor. Considering the relevance of ROS production and oxidative damage in Parkinson’s models, it is expected that the speci!city of this AOP would be high. However, with the use of PQ as a unique chemical stressor supporting the empirical evidence, judging speci!city was not possible. Overall, the strength linking the MIE to the AO was considered high for this AOP; however, using PQ as a chemical tool, the reproducibility of some experimental evidence and the specificity of the association was considered moderate.

Uncertainties and Inconsistencies

- No direct evidence exists in the literature of PQ-induced O2°! production in vivo. The involvement of O2°! production is deduced by the ef!cacy of superoxide dismutase analogues to prevent/reduce PQ neurotoxicity.

- Besides mitochondria, cellular NADPH-oxidases (Rappold et al., 2011; Cristovao et al., 2012) also contribute to PQ-induced ROS production. Furthermore, in vitro data suggest that for time points of exposure longer than 48 h oxidative stress occurs both at mitochondria and cytosol. This makes it difficult to discriminate the source of PQ-induced ROS and the early involvement of mitochondria in vivo due to the extensive treatments and to the indirect detection of oxidative stress mainly by mean of lipid peroxidation and/or protein oxidation. Mitochondrial involvement is suggested by ex-vivo studies (Czerniczyniec et al., 2013, 2015).

- The exact molecular link from mitochondrial dysfunction to disturbed proteostasis is still unclear (Malkus et al., 2009; Zaltieri et al., 2015). Furthermore, whether impaired proteostasis and protein aggregation would cause the selective death of DA neurons in the SN still remains an uncertainty.

- The role of a-synuclein in neuronal degeneration is still unclear as well as the mechanisms leading to its aggregation.

- Priority of the pattern leading to cell death could depend on concentration, time of exposure and species/strain sensitivity; these factors have to be taken into consideration for the interpretation of the study’s result and extrapolation of potential low-dose chronic effect as this AOP refers to chronic exposure.

- Animal studies, conducted with the chemical stressor PQ, show little consistency in dose, timing of treatment, species, strain and age of animals. All these factors are included in the host susceptibility, possibly contributing to the variability observed. In particular, age and iron accumulation in SNpc are additional putative risk factors for reproducing degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in SNpc (Youdim et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005; Yin et al., 2011; Jiao et al., 2012)

- The ability of PQ to induce loss of DA neurons in SNpc in vivo is sometime equivocal and reproducibility of the finding is representing an uncertainty (Smyne et al., 2016). Some methodological biases could account for the lack of reproducibility observed in some studies (Smeyne et al., 2016); however, the same cannot be applied to all studies and the a significant controversy still remains. The role of host susceptibility factors as a matter of variability should be therefore considered.

- The model of striatal DA loss and its in"uence on motor output ganglia does not explain specific motor abnormalities observed in PD (e.g. resting tremor vs bradykinesia) (Obeso et al., 2000). Other neurotransmitters (ACh) may play additional roles in other brain areas like the olfactory bulb. Transfer to animal models of PD symptoms also represents an uncertainty.

- The role of neuronal plasticity in intoxication recovery and resilience is unclear.

- This AOP is a linear sequence of KEs. However, ROS production, mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired proteostasis are in"uencing each other and these are considered as uncertainties (Malkus et al., 2009).

- When measurement of loss of mitochondrial membrane potential is performed together with cell viability, the former is detected only in dead cells in PQ treated cells (on the contrary for MPTP and Rotenone is detected in alive cells suggesting this event precedes cell death). It is suggested that decrease PQ-induced neuronal death is independent on mitochondrial membrane potential (mmp) decrease. As such overexpression of Mn SOD (in mitochondria) prevents PQ-induced cell death but not mmp decrease (Rodriguez-Rocha, 2013).

- Paraquat-induced neurotoxicity could affect a subpopulation of DA neurons. This might explain why, once the maximum effect is reached, no further neuronal death occurs after supplementary exposures (McCormack et al., 2005). Another possibility is the development of defensive mechanisms, which preserve neurons from further toxicity. This hypothesis is consistent with the in vitro observation of an increased transcriptional activation of redoxsensitive antioxidant response elements and NF-jB, speci!cally induced from paraquat but not from rotenone and MPTP (Rodriguez-Rocha et al., 2013).

- The impact of paraquat upon the striatum appears to be somewhat less pronounced than the effects upon SN dopaminergic neuronal soma (Mangano et al., 2012). In addition, some authors have failed to find changes in striatal DA levels or behavioural impairment, even in the presence of loss of dopaminergic soma (Thiruchelvam et al., 2003). It is conceivable that compensatory/buffer downstream processes provoked by soma loss or variations in experimental design can possibly contribute to some of the inconsistencies observed across studies (Rojo et al., 2007; Prasad et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2010; Rappold et al., 2011).

- Dopaminergic neurons in SN and VTA seem to have a different susceptibility to the damage induced by paraquat (McCormack et al., 2006).

- Few hypothesis have been put forward to explain the selective vulnerability of the SN pc dopaminergic pathway, although a de!ned molecular mechanism remains elusive. Elevated iron content in this region, that increase sensitivity to redox-damage catalysing the generation of ROS (Liddell et al., 2013) and regional distribution of transporters able to uptake PQ (i.e. DAT and Oct3) in combination with a high microglia population in the nigra (Rappold et al., 2011) have been evoked.

- The vulnerability of the dopaminergic pathway still remains circumstantial. Paraquat has been proposed to pass the blood-brain-barrier by mediation of neutral amino acid transportation (Shimizu et al., 2001; McCormack and DiMonte 2003). Accumulation of paraquat in the brain is reported to be age dependent, possibly indicating a role for the blood-brain-barrier permeability (Corasaniti et al., 1991); Dication paraquat has been reported not to be a substrate for dopamine transporter (Richardson et al., 2005). Nevertheless, Rappold et al. (2011) demonstrated that radical paraquat is transported by DAT and hence how the toxicant enters into dopaminergic neurons is still unclear. One possibility is extracellular paraquat reduction by membrane-bound NADPH oxidase with the formed paraquat monocation radical entering DA neurons by neuronal DAT (Rappold et al., 2011).

- Exposure to paraquat may decrease the number of nigral neurons without triggering motor impairment (Fernagut, 2007). This can be consequent to the low level of DA reduction or limited neuronal loss observed following the treatment.

- The repeat dose administration of 10 mg/kg i.p. is likely representing the maximum tolerated dose of the chemical stressor. The observed movement disorders can, at least in part, come from systemic illness and the contribution of systemic pathological changes to the observed movement disorders cannot ruled out (Cicchetti et al., 2005).

- There is uncertainty concerning the real brain concentration that is triggering this AOP. In addition, because of the complexity of the kinetic e metabolism, including local disposition of PQ in the SNpc, extrapolation of the in vitro concentration to in vivo scenario is an uncertainty.

Weight of Evidence (WoE)

ROS generation and deregulation of ROS management by dysfunctional mitochondria is known to be a crucial event in neurodegeneration in general and for dopaminergic neurons in SNpc in particular when considering the unique susceptibility of these neurons (Fujita et al., 2014; Sanders et al., 2013). Familial forms of PD include genes (i.e. PINK1 and DJI) that are implicated in ROS management by mitochondria resulting in mitochondrial DNA damage as a downstream effect (Gandhi et al., 2009; Horowitz et al., 2010; Yao et al., 2011; Fujita et al., 2014).

Biological plausibility

The biological plausibility for the KEs relationship linking the MIE to the AO is strong based on the existing knowledge of PD pathogenesis and parkinsonian syndrome. As PQ is the only tool compound so far analysed and comprehensively studied, analogy is considered moderate as the KE relationship is only plausible based on the supporting analogy with PD, but a scienti!c understanding on the relationship between a chemically induced redox cycler and parkinsonian motor de!cits is not completely established. ROS generation is mechanistically recognised as a cause of PD and parkinsonian syndrome. Mouse and rat are the most frequently used animal models to support this AOP using the tool compound PQ. Strain differences in susceptibility are reported for the experiments conducted with the chemical stressor PQ (Prasad et al., 2009; Smyne et al., 2016). The same pattern of effects has been observed in a different test species i.e. drosophila. Overall the consistency of this AOP was considered moderate to high.

Table 4 - Biological plausibility of the KERs; WoE analysis

| Support for biological plausibility of KERs | Is there a mechanistic (i.e. structural or functional) relationship between KEup and KEdown consistent with established biological knowledge? | Strong: Extensive understanding of the KER based on extensive previous documentation and broad acceptance | Moderate: The KER is plausible based on analogy to accepted biological relationships, but scientific understanding is not completely established | Weak: There is empirical support for a statistical association between KEs but the structural or functional relationship between them is not understood |

| MIE to KE1 | Strong | Chemical redox cycler with electron reduction potential more negative than O2 are effective superoxide producer (Cohen and Doherty, 1987; Mason 1990). Based on the properties of the chemical redox cycler, mitochondria may represent the primary site for chemical redox cycling due to the electron release mainly from complex I and complex III (Selivanov et al., 2011). This has been clearly demonstrated for the chemical tool paraquat, a known redox cycler inducer, in isolated mitochondria, cells, rodents, flies and yeast (Mockett et al., 2003; Tien Nguyen-nhu and Knoops, 2003; Castello et al., 2007; Rodriguez-Rocha et al., 2013). It is well established that superoxide formation will give rise to the production of different reactive oxygen species at the mitochondria, which in turn will lead to mitochondrial dysfunction (Turrens, 2003; Andreyev et al., 2005; Murphy, 2009). Mitochondria isolated from the striatum of PQ-exposed rats overproduce ROS and are dysfunctional (Czerniczyniec et al., 2013, 2015). Similarly, knocking down mitochondrial SOD induces an excessive endogenous production of superoxide (mimicking the effect or redox cycler compounds) and alters the activity of tricarboxylic acid cycle enzymes and respiratory complexes (Hinerfeld et al., 2004). The activity of most of these enzymes is rescued via antioxidant treatment linking endogenous mitochondrial oxidative stress to mitochondrial dysfunction (Hinerfeld et al., 2004). Diquat, a potent redox cycling compound can induce ROS production following intrastriatal administration (Djukic et al. 2012), enhance reactive oxygen species production and elicits an antioxidant response in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line (Slaughter et al., 2001; Nisar et al., 2015) | ||

| KE1 to KE2 | Moderate | The weight of evidence supporting the biological plausibility behind the relationship between mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired proteostasis, including the impaired function of UPS and ALP that results in decreased protein degradation and increase protein aggregation is well documented but not fully understood. It is well established that the two main mechanisms that normally remove abnormal proteins (UPS and ALP) rely on physiological mitochondrial function. The role of oxidative stress, due to mitochondrial dysfunction, burdens the proteostasis with oxidised proteins and impairs the chaperone and the degradation systems. This leads to a vicious circle of oxidative stress inducing further mitochondrial impairment (McNaught and Jenner, 2001; Moore et al., 2005; Powers et al., 2009; Zaltieri et al., 2015). Furthermore, the interaction of mitochondrial dysfunction and UPS /ALP deregulation plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of PD (Sherer et al., 2002; Fornai et al., 2005; Pan et al., 2008; Dagda et al., 2013) | ||

| KE2 to KE3 | Moderate | It is well known that impaired proteostasis refers to misfolded and aggregated proteins including alpha-synuclein, autophagy, deregulated axonal transport of mitochondria and impaired traf!cking of cellular organelles. Evidences are linked to PD and experimental PD models as well as from genetic studies (McNaught et al., 2001, 2003, 2004; Matsuda and Tanaka, 2010; Rappold et al., 2014; Tieu et al., 2014). Strong evidence for degeneration of the nigrostriatal pathway comes from the experimental manipulations that directly induce the same disturbances of proteostasis as observed in PD patients (e.g. viral mutated alpha-synuclein expression). However, a clear mechanistic proof for the understanding of the exact event triggering cell death is lacking | ||

| KE3 to AO | Strong | The mechanistic understanding of the regulatory role of striatal DA in the extrapyramidal motor control system is well established. The loss of DA in the striatum is characteristic of all aetiologies of PD and is not observed in other neurodegenerative diseases (Bernheimer et al., 1973; Reynolds et al., 1986). Characteristic motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, tremor, or rigidity are manifested when more than 80% of striatal DA is depleted as a consequence of SNpc DA neuronal degeneration (Koller et al., 1992), possibly corresponding to approximately 60% of neuronal cell loss (Jellinger et al., 2009). However, when considering these quantitative thresholds, experimental evidences with the tool chemical paraquat are inconsistent | ||

Empirical support

The empirical support provides evidence that the KEup is linked to KEdown. With PQ, as the only available chemical tool, the strength of this relationship is limited by the fact that the large majority of studies are conducted at !xed doses and single time-point descriptive assessment. This affected the dose response and incidence concordance analysis and the overall concordance for empirical support was considered moderate. The empirical support in-vivo is mainly provided by studies conducted with PQ in rodents species and drosophila aimed to model PD. In vitro the concentration-response concordance was more evident.

Table 5 - Empirical support for the KERs; WoE analysis

| Empirical support for KERs | Does the empirical evidence support that a change in the KEup leads to an appropriate change in the KEdown? Does KEup occur at lower doses and earlier time points than KEdown and is the incidence of KEup higher than that for KEdown? Are inconsistencies in empirical support cross taxa, species and stressors that don’t align with expected pattern of hypothesised AOP? | Strong: Multiple studies showing dependent change in both exposure to a wide range of specific stressors (extensive evidence for temporal, dose–response and incidence concordance) and no or few critical data gaps or conflicting data | Moderate: Demonstrated dependent change in both events following exposure to a small number of specific stressors and some evidence inconsistent with expected pattern that can be explained by factors such as experimental design, technical considerations, differences among laboratories, etc | Weak: Limited or no studies reporting dependent change in both events following exposure to a specific stressor (i.e. endpoints never measured in the same study or not at all); and/or significant inconsistencies in empirical support across taxa and species that don’t align with expected pattern for hypothesised AOP |

| MIE to KE1 | Moderate | With the chemical tool paraquat, studies are mainly conducted at !xed doses and dose relationships studies are very limited for the O2 production, which is relevant for the intra MIE dose relationship (Cantu et al., 2011; Mitra et al. 2011; Dranka et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2012; Rodriguez-Rocha et al., 2013; De Oliveira et al., 2016). However, intra KE1 dose relationship is observable for ROS production/lipid peroxidation using the same stressor compound (McCormack et al., 2005; Mitra et al., 2011; Lopert et al., 2012; de Oliveira et al., 2016). In-vitro, high concentrations of PQ showing activation of the MIE are showing the most pronounced ROS production indicating that a concordance in dose and response relationship exists between the MIE and KE1 and cell death (Chau et al., 2009; Lopert et al., 2012; Rodriguez-Rocha et al. 2013; de Oliveira et al., 2016). Temporal relationship between MIE and KE1 is indistinguishable due to the fast conversion of O2 to H2O2 and other ROS species (Cohen and Doherty, 1987). However, when considering cell death as the observational end point, a dose response and time concordance exists. PQ (0.1–1 mM) induces O2- and H2O2 production within minutes in isolated mitochondria and mitochondrial brain fraction (Castello et al., 2007; Cocheme and Murphy, 2008), while in cells this process is detectable after 4–6 h from the exposure (Cantu et al., 2011; Dranka et al. 2012; Huang et al., 2012; Rodriguez-Rocha et-al., 2013). At these time points no death is generally detected. In-vivo, there is limited evidence of intra MIE dose relationship with paraquat and temporal concordance cannot be de!ned as the experiments are conducted at single time point descriptive assessment (Mitra et al., 2011). However, circumstantial evidences are supported by the knowledge on the chronic and progressive nature of parkinsonian syndromes | ||

| KE1 to KE2 | Low | Evidence is provided that exposure to PQ and deficiency of DJ-1 might cooperatively induce mitochondrial dysfunction resulting in ATP depletion and contribute to proteasome dysfunction in mouse brain (Yang et al., 2007). Moreover, exacerbation of Paraquat effect on the autophagic degradation pathway is observed in an in vitro system with silenced DJ-1 (Gonzalez-Polo et al., 2009). In C57BL/6J mice 10 mg/kg i.p. for 1–5 doses, increased level of lipid peroxides in ventral midbrain was associated impaired proteostasis (Prasad et al., 2007) Temporal and dose concordance cannot be elaborated from in vivo studies as they are conducted at the same dose and observational time-point. However, in vitro studies are indicative of a temporal and concentration concordance, evidencing concentration-and/or time-dependent effects on mitochondrial and proteasome functions (Ding and Keller, 2001; Yang and Tiffany-Castiglioni, 2007) | ||

| KE2 to KE3 | Moderate | The empirical support linking impaired proteostasis with degeneration of DA neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway comes from post-mortem human evidences in PD patients supporting a causative link between the two key events.. With paraquat, a response concordance was observed in multiple in vivo studies (Manning-Bog, 2003; Fernagut, 2007; Mitra, 2011). Temporal and dose concordance cannot be elaborated from these studies as they are conducted at the same dose and observational time-point. Some inconsistencies were observed, i.e. partial effect on proteasomal inhibition which is likely due to compensatory effects and/or lower toxicity of PQ when compared to other chemical stressor (e.g. rotenone, MPTP) In vivo studies with Paraquat are showing a more relevant effect on the ALP and a-synuclein overexpression with a less evident effect on proteasome inhibition. A dose and temporal concordance was more consistently observed in in vitro studies (Gonzalez-Polo, 2009; Chinta, 2010) | ||

| KE3 to AO | Moderate to low | PQ is reported to induce motor de!cits and loss of nigral dopaminergic neurons in a dose-(Brooks et al., 1999) and age (Thiruchelvam et al., 2003) dependent manner. The concomitant observation of dopaminergic neuronal loss and parkinsonian motor symptoms has been con!rmed by other authors (Cicchetti et al., 2005; Prasad et al., 2009; Mitra et al., 2011). However, at similar doses and experimental design a number of inconsistencies or lack of reproducibility were noted and described in the uncertainties (Smyne et al., 2016). In human (and animal models using rotenone and MPTP), motor symptoms are expected to be clinically visible when striatal dopamine levels drop of approximately 80%, corresponding to a DA neuronal loss of approximately 60% (Bernheimer et al., 1973; Lloyd et al., 1975; Hornykiewicz et al., 1986; Jellinger et al., 2009). This threshold of pathological changes was only achieved when paraquat was administered directly in the SN and the link between neuronal loss and clinical symptoms was empirically consolidated by the following treatment with apomorphine or the concomitant treatment with the MAOB inhibitors (Liou, 1996, 2001). When different routes of administration were applied, neuronal loss was below this pathological threshold, not consistently related to drop in striatal DA and motor symptoms were only occasionally observed (Smyne et al., 2016). Some methodological biases can explain the inconsistency in the lack of reproducibility observed for some experiments conducted in-vivo with the chemical stressor PQ (Smyne et al., 2016); however, when considering the multiple factors associated with host susceptibility and the complexity of the local disposition of PQ i.e. concentration and activation of PQ in the SNpc and striatum, the biological variability can account for the different outcomes observed in the studies | ||

Known Modulating Factors

| Modulating Factor (MF) | Influence or Outcome | KER(s) involved |

|---|---|---|

|

mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), mitochondrial Cu superoxide dismutase (CuSOD) , mitochondrial Zn superoxide dismutase (ZnSOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPX1 and GPX4) and peroxiredoxin (Prx), Coenzyme Q |

Antioxydant enzymes, preserve mitochondrial integrity |

3629 3650 |

Quantitative Understanding

The quantitative understanding of this AOP includes evidence of response–response relationship and the identi!cation of a putative threshold effect. This is because the triggering effect at MIE level was explored in only few studies and the reproducibility of the KE 3 is likely depending by multiple host susceptibility factors. More evidence exists that an increase from 200% to 600% of lipid peroxidation (endpoint of KE1) in DA neuronal cells can be used as a probabilistic threshold triggering the degeneration of DA neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway. In line with others chemical tools that can induce DA neuronal loss through different MIE (i.e. rotenone and MPTP), for the identi!cation of the AO the design of the in-vivo studies should be tailored as to a MIE which leads to a long-lasting perturbation of the KEs. This provides the most specific and definite context to trigger neuronal death in vivo. A major hurdle for this AOP is represented by the AO. With PQ, the low level of reported DA neuronal loss (ca. 20–30%) is not expected to induce parkinsonian motor symptoms and essentiality data (i.e. recovery of motor symptoms following treatment with DA) is limited. Moving from a qualitative AOP to quantitative AOP would need a clear understanding of effect thresholds for the different KEs.

Table 6 - Concordance table for the tool compound paraquat

| Dose/concentration at the target site | MIE | KE1 - Elevetad mitochondrial ROS, dysfunction | KE2 - Impaired, proteostasis | KE3- Degeneration of DA neurons of nigrostriatal pathway | AO - Parkinsonian motor symptoms |

| 0.78 uM brain concentration [1 and 2] | No data | 200% increase in lipid peroxidation [4] | No data | No effect [4] | No data |

| Below 3 uM (intended as a cumulative concentration; 8 doses) [8] | 42% increase in SOD activity [8] | No data | 10% decrease in TH+ neurons [8] | No data | |

| 3–10 uM (cumulative concentration after multiple doses) [1 and 2] | 75% increase in SOD activity [8] | 500–600% (cumulative effect) lipid peroxidation [2, 4] | 50% increase in 20S proteasome fraction at 24 h [2] Intracellular deposits of a-synuclein in 30% of DA neurons [6] 50% increase in a-synuclein expression [8] | 30–50% (cumulative effect) decrease in TH+ neurons [2,4, 6, 7, 8] | Motor impairment [2, 8, 10] |

References: Breckenridge 2013 [1]; Prasad 2007 and 2009 [2]; Castello 2007 [3]; Mc Cormack 2005 [4]; Cantu 2011 [5]; Manning-Bog 2003 [6]; Fernagut 2007 [7]; Mitra 2011 [8]; Yang 2007 [9]; Brooks 1999 [10].

Considerations for Potential Applications of the AOP (optional)

Regulatory considerations

The AOP is a conceptual framework to mechanistically understand apical hazards. The AO, parkinsonian motor symptoms, is an apical endpoint that can be explored and quantified in the regulatory toxicology studies conducted in experimental laboratory animals. Motor deficit endpoints, and their relevance to parkinsonian disorders and PD are a matter of intensive discussion in the scientific community. The use of rodent models for assessment of parkinsonian/PD-associated motor deficits was even put into question. Although rodent motor output can only hardly be correlated with the human motor output repertoire, the adverse outcome of the present AOP was explicitly focused on alterations in motor output associated with parkinsonian conditions. Indeed, this AOP does not claim that motor de!cits included herein re"ect the complexity of the human disease. It is also noteworthy that decrease in neuronal cell count is also an apical regulatory endpoint explorable and quanti!able in experimental studies conducted in vivo; if the appropriate areas of the brain are sampled and properly evaluated. A statistically signi!cant decrease in DA neuronal cell count is considered an adverse event, regardless of the concomitant presence of motor symptoms. This has to be taken into consideration for the potential regulatory applications of this AOP and for the sensibility of the method applied to capture the KE/apical endpoint/hazard. If the intention is to use

Potential applications

This AOP was developed in order to evaluate the biological plausibility that the adverse outcome i.e.parkinsonian motor de!cits, is linked to the selected MIE. By means of using a human health outcome from epidemiological studies and meta-analysis, the authors intend to embed the AO in the process of hazard identi!cation and identification of risk factors. In addition, this AOP can be used to support identification of data gap that can be required or explored when a chemical substance is affecting the pathway or provide recommendation on the most adequate study design that can be applied to investigate the apical endpoints. It is important to note that, although the AO is defined in this AOP as parkinsonian motor de!cits, degeneration of DA neurons is already per se an adverse event even in situations where is not leading to parkinsonian motor deficits or clinical signs indicative of a central effect, and this should be taken into consideration for the regulatory applications of this AOP. In addition, this AOP can inform on the identifications of in vitro methods that can be developed for an integrated approach to testing and assessment (IATA) based on in vitro neurotoxicity assays complementary to in vivo assays.

References

Andreyev AY1, Kushnareva YE, Starkov AA, 2005. Mitochondrial metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry (Mosc), 70, 200–214.

Barlow BK, Richfield EK, Cory-Slechta DA, Thiruchelvam M, 2004. A fetal risk factor for Parkinson’s disease. Developmental Journal of Neuroscience, 26, 11–23. Epub 2004/10/29. doi: DNE2004026001011 [pii] 10.1159/ 000080707 [doi]. PubMed PMID: 15509894.

Bernheimer H, Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O, Jellinger K, Seitelberger F, 1973. Brain dopamine and the syndromes of Parkinson and Huntington. Clinical, Morphological and Neurochemical Correlations. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 20, 415–455.

Betarbet R, Sherer TB, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov AV, Greenamyre JT, 2000. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nature Journal of Neuroscience, 3, 1301–1306.

Betarbet R, Canet-Aviles RM, Sherer TB, Mastroberardino PG, Mc Lendon C, Kim JH, Lund S, Na HM, Taylor G Bence NF, Kopito R, Seo BB, Yagi T, Yagi A, Klinfelter G, Cookson MR, Greenmyre JT, 2006. Intersecting pathways to neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease: effects of the pesticide rotenone on DJ-1, a-synuclein, and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Neurobiology Disease, 22, 404–420.

Bingol B, Tea JS, Phu L, Reichelt M, Bakalarski CE, Song Q, Foreman O, Kirkpatrick DS, Sheng M, 2014. The mitochondrial deubiquitinase USP30 opposes parkin-mediated mitophagy. Nature, 510, 370–375. doi: 10.1038/ nature13418

Brown GC, Bal-Price A, 2003. In"ammatory neurodegeneration mediated by nitric oxide, glutamate, and mitochondria. Molecular Neurobiology, 27, 325–355.

Breckenridge CB, Sturgess NC, Butt M, Wolf JC, Zadory D, Beck M, Mathews JM, Tisdel MO, Minnema D, Travis KZ,Cook AR, Botham PA, Smith LL, 2013. Pharmacokinetic, neurochemical, stereological and neuropathological studies on the potential effects of paraquat in the substantia nigra pars compacta and striatum of male C57BL/ 6J mice. Neurotoxicology, 37, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.03.005

Brooks AI, Chadwick CA, Gelbard HA, Cory-Slechta DA, Federoff HJ, 1999. Paraquat elicited neurobehavioral syndrome caused by dopaminergic neuron loss. Brain Research, 823, 1–10.

Cantu D, Fulton RE, Drechsel DA, Patel M, 2011. Mitochondrial aconitase knockdown attenuates paraquat-induced dopaminergic cell death via decreased cellular metabolism and release of iron and H2O2. Journal of Neurochemistry, 118, 79–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07290.x

Castello PR, Drechsel DA, Patel M, 2007. Mitochondria are a major source of paraquat-induced reactive oxygen species production in the brain. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 282, 14186–14193.

Chao CC, Hu S, Peterson PK, 1995. Glia, cytokines, and neurotoxicity. Critical ReviewsTM in Neurobiology, 9, 189– 205.

Chau KY, Korlipara LV, Cooper JM, Schapira AH, 2009. Protection against paraquat and A53T alpha-synuclein toxicity by cabergoline is partially mediated by dopamine receptors. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 278, 44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.11.012

Chau KY, Cooper JM, Schapira AH, 2010. Rasagiline protects against alpha-synuclein induced sensitivity to oxidative stress in dopaminergic cells. Neurochemistry International, 57, 525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010. 06.017

Choi HS, An JJ, Kim SY, Lee SH, Kim DW, Yoo KY, Won MH, Kang TC, Kwon HJ, Kang JH, Cho SW, Kwon OS, Park J, Eum WS, Choi SY, 2006. PEP-1-SOD fusion protein efficiently protects against paraquat-induced dopaminergic neuron damage in a Parkinson disease mouse model. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 41, 1058–1068.

Chou AP, Li S, Fitzmaurice AG, Bronstein JM, 2010. Mechanisms of rotenone-induced proteasome inhibition. NeuroToxicology, 31, 367–372.

Cicchetti F, Lapointe N, Roberge-Tremblay A, Saint-Pierre M, Jimenez L, Ficke BW, Gross RE, 2005. Systemic exposure to paraquat and maneb models early Parkinson’s disease in young adult rats. Neurobiology of Disease, 20, 360–371.

Cocheme HM, Murphy MP, 2009. Chapter 22 The uptake and interactions of the redox cycler paraquat with mitochondria. Methods in Enzymology, 456, 395–417. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04422-4

Cohen GM, d’Arcy Doherty M, 1987. Free radical mediated cell toxicity by redox cycling chemicals. British Journal of Cancer. Supplement, 8, 46–52.

Corasaniti MT, Defilippo R, Rodinho P, Nappi G, Nistic#o G, 1991. Oct-Dec Evidence that paraquat is able to cross the blood-brain barrier to a different extent in rats of various age. Functional Neurology, 6, 385–391.

Cristovao AC, Choi DH, Baltazar G, Beal MF, Kim YS, 2009. The role of NADPH oxidase 1-derived reactive oxygen species in paraquat-mediated dopaminergic cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal, 11, 2105–2118. doi: 10.1089/ ARS.2009.2459

Czerniczyniec A, Lores-Arnaiz S, Bustamante J, 2013. Mitochondrial susceptibility in a model of paraquat neurotoxicity. Free Radical Research, 47, 614–623. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2013.806797

Czerniczyniec A, Lanza EM, Karadayian AG, Bustamante J, Lores-Arnaiz S, 2015. Impairment of striatal mitochondrial function by acute paraquat poisoning. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes, 47, 395–408. doi: 10.1007/s10863-015-9624-x

Dagda RK, Banerjee TD, Janda E, 2013. How Parkinsonian toxins dysregulate the autophagy machinery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 14, 22163–22189.

Dauer W, Kholodilov N, Vila M, Trillat AC, Goodchild R, Larsen KE, Staal R, Tieu K, Schmitz Y, Yuan CA, Rocha M, Jackson-Lewis V, Hersch S, Sulzer D, Przedborski S, Burke R, Hen R, 2002. Resistance of alpha -synuclein null mice to the parkinsonian neurotoxin MPTP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99, 14524–14529.

Day BJ, Patel M, Calavetta L, Chang LY, Stamler JS, 1999. A mechanism of paraquat toxicity involving nitric oxide synthase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96, 12760–12765.

de Oliveira MR, Ferreira GC, Schuck PF, 2016. Protective effect of carnosic acid against paraquat-induced redox impairment and mitochondrial dysfunction in SH-SY5Y cells: role for PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway. Toxicology in Vitro, 32, 41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.12.005

Ding Q, Keller JN, 2001. Proteasome inhibition in oxidative stress neurotoxicity: implications for heat shock proteins. Journal of Neurochemistry. 77, 1010–1017.

Djukic M, Jovanovic MD, Ninkovic M, Stevanovic I, Curcic M, Topic A, Vujanovic D, Djurdjevic D, 2012. Intrastriatal pre-treatment with L-NAME protects rats from diquat neurotoxcity. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 19, 666–672.

Dranka BP1, Zielonka J, Kanthasamy AG, Kalyanaraman B. Alterations in bioenergetic function induced by Parkinson’s disease mimetic compounds: lack of correlation with superoxide generation. Journal of Neurochemistry, 122, 941–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07836.x

Fei Q, McCormack AL, Di Monte DA, Ethell DW, 2008. Paraquat neurotoxicity is mediated by a Bak-dependent mechanism. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283, 3357–3364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708451200

Fernagut PO, Fleming SM, Houston CB, Tetreaut NA, Salcedo L, Masliah E, Chesselet MF, 2007. Behavioural and histological consequences of paraquat intoxication in mice: effect of a-synuclein over expression. Synapse, 61, 991–1001.

Filograna R, Godena VK, Sanchez-Martinez A, Ferrari E, Casella L, Beltramini M, Bubacco L, Whitworth AJ, Bisaglia M, 2016. SOD-mimetic M40403 is protective in cell and "y models of paraquat toxicity: implications for Parkinson disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry, pii: jbc.M115.708057.

Fornai F, Schl€uter OM, Lenzi P, Gesi M, Ruffoli R, Ferrucci M, Lazzeri G, Busceti CL, Pontarelli F, Battaglia G, Pellegrini A, Nicoletti F, Ruggieri S, Paparelli A, S€udhof TC, 2005. Parkinson-like syndrome induced by continuous MPTP infusion: convergent roles of the ubiquitinproteasome system and _a-synuclein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102, 3413–3418.

Freed CR, Breeze RE, Rosenberg NL, Schneck SA, Wells TH, Barrett JN, Grafton ST, Huang SC, Eidelberg D, Rottenberg DA, 1990. Transplantation of human fetal dopamine cells for Parkinson’s disease. Results at 1 year. Archives of Neurology, 47, 505–512.

Fujita KA, Ostaszewski M, Matsuoka Y, Ghosh S, Glaab E, Trefois C, Crespo I, Perumal TM, Jurkowski W, Antony PM, Diederich N, Buttini M, Kodama A, Satagopam VP, Eifes S, Del Sol A, Schneider R, Kitano H, Balling R, 2014. Integrating pathways of Parkinson’s disease in a molecular interaction map. Molecular Neurobiology, 49, 88–102.

Gandhi S, Wood-Kaczmar A, Yao Z, et al., PINK1-associated Parkinson’s disease is caused by neuronal vulnerability to calcium-induced cell death. Molecular Cell, 33, 627–638.

Garcia-Garcia A, Anandhan A, Burns M, Chen H, Zhou Y, Franco R, 2013. Impairment of Atg5-dependent autophagic "ux promotes paraquat- and MPP+-induced apoptosis but not rotenone or 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity. Toxicological Sciences, 136, 166–182. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft188

Gonzalez-Polo RA, Niso-Santano M, Ortiz-Ortiz MA, G!omez-Mart!ın A, Mor!an JM, Garc!ıa-Rubio L, Francisco-Morcillo J, Zaragoza C, Soler G, Fuentes JM, 2007. Inhibition of paraquat-induced autophagy accelerates the apoptotic cell death in neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Toxicological Sciences, 97, 448–458.

Gonzalez-Polo R, Niso-Santano M, Mor!an JM, Ortiz-Ortiz MA, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Soler G, Fuentes JM, 2009. Silencing DJ-1 reveals its contribution in paraquat-induced autophagy. Journal of Neurochemistry, 109, 889–898.

Han F, Baremberg D, Gao J, Duan J, Lu X, Zhang N, Chen Q, 2015. Development of stem cell-based therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Translational Neurodegeneration, 4, 16.

Henderson BT, Clough CG, Hughes RC, Hitchcock ER, Kenny BG, 1991. Implantation of human fetal ventral mesencephalon to the right caudate nucleus in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Archives of Neurology, 48, 822–827.

Hinerfeld D, Traini MD, Weinberger RP, Cochran B, Doctrow SR, Harry J, Melov S, 2004. Endogenous mitochondrial oxidative stress: neurodegeneration, proteomic analysis, specific respiratory chain defects, and ef!cacious antioxidant therapy in superoxide dismutase 2 null mice. Journal of Neurochemistry, 88, 657–667.

Hirsch EC, Hunot S, 2009. Neuroin"ammation in Parkinson’s disease: a target for neuroprotection? Lancet Neurology, 8, 382–397. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70062-6

Hornykiewicz O, Kish SJ, Becker LE, Farley I, Shannak K, 1986. Brain neurotransmitters in dystonia musculorum deformans. New England Journal of Medicine, 315, 347–353.

Horowitz MP, Greenamyre JT, 2010. Gene-environment interactions in parkinson’s disease: the importance of animal modelling. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 88, 467–474.

Huang CL, Lee YC, Yang YC, Kuo TY, Huang NK, 2012. Minocycline prevents paraquat-induced cell death through attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Toxicology Letters, 209, 203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.12.021

Jellinger AK, 2009. A critical evaluation of current staging of a-synuclein pathology in Lewy body disorders. Biochemica and Biophysica Acta, 1972, 730–740.

Jiao Y, Lu L, Williams RW, Smeyne RJ, 2012. Genetic dissection of strain dependent paraquat-induced neurodegeneration in the substantia nigra pars compacta. Public Library of Science (PLoS ONE), 7, e29447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029447

Jimenez-Del-Rio M, Guzman-Martinez C, Velez-Pardo C, 2010. The effects of polyphenols on survival and locomotor activity in Drosophila melanogaster exposed to iron and paraquat. Neurochemical Research, 35, 227–238.

Jones BC, Huang X, Mailman RB, Lu L, Williams RW, 2014. The perplexing paradox of paraquat: the case for hostbased susceptibility and postulated neurodegenerative effects. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology, 28, 191–197. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21552

Kang MJ, Gil SJ, Lee JE, Koh HC, 2010. Selective vulnerability of the striatal subregions of C57BL/6 mice to paraquat. Toxicology Letters, 195, 127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.03.011

Kirby K, Hu J, Hilliker AJ, Phillips JP, 2002. RNA interference-mediated silencing of Sod2 in Drosophila leads to early adult-onset mortality and elevated endoge-nous oxidative stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99, 16162–16167.

Kirk D, Rosenblad C, Burger C, Lundberg C, Johansen TE, Muzyczka N, Mandel R, Bijorklund A, 2002. Parkinsonlike neurodegeneration induced by targeted overexpression of a-synuclein in the nigrostriatal system. 22, 2780–2791.

Kirk D, Annett L, Burger C, Muzyczka N, Mandel R, Bijorklund A, 2003. Nigrostriatal a-synucleinopathy induced by viral vector-mediated overexpression of human a-synuclein: a new primate model of parkinson’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100, 2884–2889.

Klein RL, King MA, Hamby ME, Meyer EM, 2002. Dopaminergic cell loss induced by human A30P a-synuclein gene transfer to the rat substantia nigra. Human Gene Therapy, 13, 605–612.

Koller WC, 1992. When does Parkinson’s disease begin? Neurology, 42(4 Suppl 4), 27–31.

Kraft AD, Harry GJ, 2011. Features of microglia and neuroin"ammation relevant to environmental exposure and neurotoxicity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8, 2980–3018.

Khwaja M, McCormack A, McIntosh JM, Di Monte DA, Quik M, 2007. Nicotine partially protects against paraquatinduced nigrostriatal damage in mice; link to alpha6beta2* nAChRs. Journal of Neurochemistry, 100, 180–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04177.x

Lauwers E, Debyser Z, Van Drope J, DeStrooper B, Nuttin B, 2003. Neuropathology and neurodegeneration in rodent brain induced by lentiviral vector-mediated overexpression of a-synuclein. Brain Pathology, 13, 364–372.

Li X, Cheng CM, Sun JL, Li Z, Wu YI, 2005. Paraquat induces selective dopaminergic nigrostriatal degeneration in aging C57BL/6J mice. Chinese Medical Journal, 118, 1357–1361.

Li H, Wu S, Wang Z, Lin W, Zhang C, Huang B, 2012. Neuroprotective effects of tert-butylhydroquinone on paraquat-induced dopaminergic cell degeneration in C57BL/6 mice and in PC12 cells. Archives of Toxicology,86, 1729–1740. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0935-y

Liang LP, Kavanagh TJ, Patel M, 2013. Glutathione de!ciency in Gclm null mice results in complex I inhibition anddopamine depletion following paraquat administration Toxicological Sciences, 134, 366–373. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft112

Liddell JR, Obando D, Liu J, Ganio G, Volitakis I, Mok SS, Crouch PJ, White AR, Codd R, 2013. Lipophilic adamantyl- or deferasirox-based conjugates of desferrioxamine B have enhanced neuroprotective capacity: implications for Parkinson disease. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 60, 147–156.

Liou HH, Chen RC, Tsai YF, Chen WP, Chang YC, Tsai MC, 1996. Effects of paraquat on the substantia nigra of the Wistar rats: neurochemical, histological, and behavioral studies. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 137, 34–41.

Liou HH, Chen RC, Chen TH, Tsai YF, Tsai MC, 2001. Attenuation of paraquat-induced dopaminergic toxicity on the substantia nigra by (-)-deprenyl in vivo. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 172, 37–43.

Lloyd KG, Davidson L, Hornykiewicz O, 1975. The neurochemistry of Parkinson’s disease: effect of L-dopa therapy. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 195, 453–464.

Lo Bianco C, Ridet JL, Deglon N, Aebischer P, 2002. Alpha-synucleopathy and selective dopaminergic neuron loss in a rat lentiviral-based model of Parkinson’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99, 10813–10818.

Lopert P, Day BJ, Patel M, 2012. Thioredoxin reductase de!ciency potentiates oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in dopaminergic cells. Public Library of Science (PLoS ONE), 7, e50683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050683

Lopez-Lozano JJ, Bravo G, Abascal J, 1991. Grafting of perfused adrenal medullary tissue into the caudate nucleus of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Clinica Puerta de Hierro Neural Transplantation Group. Journal of Neurosurgery, 75, 234–243.

Malkus KA, Tsika E, Ischiropoulos H, 2009. Oxidative modi!cations, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired protein degradation in Parkinson’s disease: how neurons are lost in the Bermuda triangle. Molecular Neurodegeneration, 4, 24. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-24

Mangano EN, Litteljohn D, So R, Nelson E, Peters S, Bethune C, et al., 2012. Interferon-gamma plays a role in paraquat-induced neurodegeneration involving oxidative and proin"ammatory pathways. Neurobiology of Aging, 33, 1411–1426.

Mangano EN, Hayley S, 2009. In"ammatory priming of the substantia nigra in"uences the impact of later paraquat exposure: Neuroimmune sensitization of neurodegeneration. Neurobiology of Aging, 30, 1361–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.11.020

Mangano EN, Peters S, Litteljohn D, So R, Bethune C, Bobyn J, et al., 2011. Granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor protects against substantia nigra dopaminergic cell loss in an environmental toxin model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of Disease, 43, 99–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.02.011

Manning-Bog AB, McCormack AL, Purisai MG, Bolin LM, Di Monte DA, 2003. Alpha-synuclein overexpression protects against paraquat-induced neurodegeneration. Journal of Neuroscience, 23, 3095–3099.

Mason RP, 1990. Redox cycling of radical anion metabolites of toxic chemicals and drugs and the Marcus theory of electron transfer. Environmental Health Perspectives, 87, 237–243.

Matsuda N, Tanaka K, 2010. Does impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system or the autophagy-lysosome pathway predispose individuals to neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease? Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 19, 1–9. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1231

McCarthy S, Somayajulu M, Sikorska M, Borowy-Borowski H, Pandey S, 2004. Paraquat induces oxidative stress and neuronal cell death; neuroprotection by water-soluble Coenzyme Q10. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 201, 21–31.

McCormack AL, Thiruchelvam M, Manning-Bog AB, Thiffault C, Langston JW, Cory-Slechta DA, Di Monte DA, 2002. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson’s disease: selective degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons caused by the herbicide paraquat. Neurobiology of Disease, 10, 119–127.

McCormack AL, Di Monte DA, 2003. Effects of L-dopa and other amino acids against paraquat-induced nigrostriataldegeneration. Journal of Neurochemistry, 85, 82–86.

McCormack AL1, Atienza JG, Johnston LC, Andersen JK, Vu S, Di Monte DA, 2005. Role of oxidative stress in paraquat-induced dopaminergic cell degeneration. Journal of Neurochemistry, 93, 1030–1037.

McCormack AL, Atienza JG, Langston JW, Di Monte DA, 2006. Decreased susceptibility to oxidative stress underlies the resistance of speci!c dopaminergic cell populations to paraquat-induced degeneration. Journal of Neuroscience, 141, 929–937.

McNaught KS, Jenner P, 2001. Proteasomal function is impaired in substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience Letters, 297, 191–194.

McNaught KS, Belizaire R, Isacson O, Jenner P, Olanow CW, 2003. Altered proteasomal function in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Experimental Neurology, 179, 38–46.

McNaught KS, Perl DP, Brownell AL, Olanow CW, 2004. Systemic exposure to proteasome inhibitors causes a progressive model of Parkinson’s disease. Annals of Neurology, 56, 149–162.

Minnema DJ, Travis KZ, Breckenridge CB, Sturgess NC, Butt M, Wolf JC, Zadory D, Beck MJ, Mathews JM, Tisdel

MO, Cook AR, Botham PA, Smith LL, 2014. Dietary administration of paraquat for 13 weeks does not result in a loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of C57BL/6J mice. 68, 250–258.

Mitra S, Chakrabarti N, Bhattacharyy A, 2011. Differential regional expression patterns of a-synuclein, TNF-a, and IL-1b; and variable status of dopaminergic neurotoxicity in mouse brain after Paraquat treatment. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 8, 163.

Mockett RJ, Bayne AC, Kwong LK, Orr WC, Sohal RS, 2003. Ectopic expression of catalase in Drosophila mitochondria increases stress resistance but not longevity. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 34, 207–217.

Moore DJ, West AB, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, 2005. Molecular pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 28, 57–87.

Murphy MP, 2009. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species Biochemical Journal, 417, 1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386

Muthukumaran K, Leahy S, Harrison K, Sikorska M, Sandhu JK, Cohen J, Keshan C, Lopatin D, Miller H, Borowy-Borowski H, Lanthier P, Weinstock S, Pande S, 2014. Orally delivered water soluble Coenzyme Q10 (Ubisol-Q10) blocks on-going neurodegeneration in rats exposed to paraquat: potential for therapeutic application in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience, 15, 21.

Nisar R, Hanson PS, He L, Taylor RW, Blain PG, Morris CM, 2015. Diquat causes caspase-independent cell death in SH-SY5Y cells by production of ROS independently of mitochondria. Archives of Toxicology, 89, 1811–1825. doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1453-5

Nuber S, Tadros D, Fields J, Overk CR, Ettle B, Kosberg K, Mante M, Rockenstein E, Trejo M, Masliah E, 2014. Environmental neurotoxic challenge of conditional alpha-synuclein transgenic mice predicts a dopaminergic olfactory-striatal interplay in early PD. Acta Neuropathologicaogica, 127, 477–494. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1255-5

Obeso JA, Rodr!ıguez-Oroz MC, Rodr!ıguez M, Lanciego JL, Artieda J, Gonzalo N, Olanow CW, 2000. Pathophysiology of the basal ganglia in Parkinson’s disease. Trends in Journal of Neurosciences, 23(10 Suppl), S8–S19.