This AOP is licensed under the BY-SA license. This license allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. The license allows for commercial use. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms.

AOP: 587

Title

Inhibition of the mitochondrial complex III of nigro-striatal neurons leads to parkinsonian motor deficits

Short name

Graphical Representation

Point of Contact

Contributors

- Barbara Viviani

- Giacomo Grumelli

Coaches

OECD Information Table

| OECD Project # | OECD Status | Reviewer's Reports | Journal-format Article | OECD iLibrary Published Version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

This AOP was last modified on December 08, 2025 02:48

Revision dates for related pages

| Page | Revision Date/Time |

|---|---|

| Increase, Mitochondrial dysfunction | February 11, 2026 07:06 |

| Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway | October 01, 2025 07:04 |

| Parkinsonian motor deficits | March 12, 2018 12:44 |

| Inhibition, Mitochondrial complex III | October 03, 2025 19:05 |

| Inhibition, Mitochondrial complex III leads to Increase, Mitochondrial dysfunction | October 02, 2025 05:33 |

| Increase, Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway | October 03, 2025 17:52 |

| Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway leads to Parkinsonian motor deficits | October 03, 2025 18:38 |

| Antimycin A | December 19, 2018 09:50 |

| Picoxystrobin | September 29, 2025 03:42 |

Abstract

This Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) describes the mechanistic link between the inhibition of mitochondrial complex III (cIII) and the development of parkinsonian motor deficits. It is developed upon the previously endorsed AOP3 (focused on complex I inhibition) and expands the AOP network to include cIII as a molecular initiating event (MIE). The pathway is supported by evidence from human genetic studies, in vitro models, and quantitative data analyses. Key events (KEs) include mitochondrial dysfunction, degeneration of dopaminergic neurons, and motor deficits. The AOP is characterised by strong biological plausibility and empirical support, particularly for the early KEs. To support regulatory application, a quantitative AOP (qAOP) framework was applied to model key event relationships (KERs) using dose–response data and Bayesian parameterization. This approach enabled the integration of data from multiple compounds. However, several uncertainties affect the quantitative understanding of this AOP. These include the lack of dose–response data for cIII inhibition in dopaminergic LUHMES cells, reliance on surrogate data from liver-derived HepG2 cells, and the use of glucose-rich media in most assays, which may mask mitochondrial vulnerability due to compensatory glycolysis. Additionally, an exposure duration of 24 hours, as the one used in the key studies, may be insufficient to detect downstream effects and, for some early KEs may result in a loss of temporal resolution determining an excessive steepness of the dose–response curve. The use of permeabilized cells for MIE measurements also introduces uncertainty regarding comparability of intracellular exposure with KEs measured in intact cells. Finally, while upstream key events are well-supported, direct in vivo evidence linking cIII inhibition to parkinsonian motor deficits remains limited.

AOP Development Strategy

Context

Evidence from literature consistently indicates that a relationship exists between pesticide exposure and the onset of parkinsonian motor deficit (Ntzani et al., 2013). The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) started a project to provide a theoretical basis explaining the link between cI inhibition and neurotoxic adverse outcomes (manifesting in loss of dopamine neurons) (EFSA 2017). This resulted in the development of AOP 3 (inhibition of cI leading to parkinsonian motor deficits) and its endorsement by the OECD. The AOP 3 became a test/pilot case for exploring the use of AOP informed IATA in risk assessment (Bennekou et al.-OECD 2020). The AOP was initially exemplified by studies on rotenone and MPTP/MPP+. Subsequent work explored whether also the inhibition of other complexes of the respiratory chain might show similar effects. Systematic approaches, based on the 2017 version of AOP3 and case studies of regulatory relevance, indicate the contribution of the inhibition of mitochondrial complexes other than complex I, i.e. cIII (Table 1). These observations justify the integration of published data on complex III inhibition. The implementation of the AOP 3 is based on a negotiated procedure with EFSA (Reference: NP/EFSA/PREV/2024/02), which is intended to update AOP 3 by adding more evidence to the AOP wiki. The focus of the project is the transformation of AOP 3 into an AOP network for adult neurotoxicity, which involves expanding the number of MIEs.

Table 1. Application of AOP 3 in studies with regulatory relevance

|

Study |

Regulatory relevance |

ETC tested |

Reference |

|

Testing of the in vitro battery aligned with AOP3 |

Testing the applicability of several assays to form the basis of a consensus mitochondrial toxicity testing platform |

Inhibition of cI, cII or cIII |

Delp et al. 2019; van der Stel et al. 2020 |

|

Case study on the use of an IATA for mitochondrial cIII mediated neurotoxicity |

Read across safety assessment of structurally closely related mitochondrial cIII inhibitors |

Inhibition of cIII |

ENV/JM/MONO(2020)23, van der Stel, W. (2021) |

|

Testing the predictivity of the downstream events |

Testing the inhibitory potency prediction with the aim to understand how far early KE data can and will predict an AO |

Inhibition of cI, cII or cIII |

Delp et al., 2021 |

|

Hazard assessment |

Identification of the signalling network triggered by mitochondrial perturbation induced by the inhibition of cI, cII or cIII in HepG2 cells |

Inhibition of cI, cII or cIII |

Van der Stel et al., 2022 |

IATA: Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment; cI: complex, I; cII: complex II; cIII: complex III

Strategy

The starting conceptual model for this project is based on the key scientific sources, including EFSA (2017), Delp et al. (2019 and 2021), Van der Stel et al. (2020 and 2022). These publications provided the initial evidence for this project, which was further expanded through a structured literature review aimed at:

-

updating the link between mitochondrial toxicity and parkinsonian motor deficits across AOP 3

-

supporting the description of the new MIEs, KEs and KERs.

Following the AOP Development Handbook, the AOP Wiki was mapped to identify existing KEs and KERs that were common to the newly developed components of the AOP network. KE 1542 was adopted and further elaborated for the missing parts by the authors of this AOP. The procedure has been agreed with the management of AOP-wiki after contacting the author. KE177, KE 890, AO 896 and KER 908, KER 910 within the OECD-endorsed AOP3 have been updated to include data referring on cIII inhibitors. These updates have been documented in a dedicated section, in agreement with the AOP3 point of contact.

For well-established MIEs and KEs, evidence was retrieved from seminal publications recommended by domain experts and supported by expert knowledge. Additional literature was identified, through a structured, non-systematic search using a stressor-based search strategy to retrieve essentiality data and data linking KE1542/KE177 to KE890/AO through the selected stressors in in vivo studies. Tailored search strings, detailed in a dedicated section at the end of this document, were designed by two information specialists in collaboration with the project team. For each selected stressor, the information specialists conducted a literature search using a quasi-systematic approach. They employed both textwords and database-specific subject headings where available, across the following databases: PubMed, Embase via Elsevier, Web of Science via Clarivate, and Scopus. Any additional relevant literature identified by examining the reference list of included studies was included if met the eligibility criteria.

The following criteria were applied to select relevant studies.

Publication type

|

Time |

IN |

Inception – present or 2017- present |

|

Language |

IN |

English |

|

Publication type |

IN |

·Primary research studies ·Reviews |

|

OUT |

·Expert opinions ·editorials ·letters to the editor ·conference proceedings and posters ·retracted articles ·PhD thesis |

In vitro studies

|

Study design |

IN |

Any In vitro study design |

|

Population |

IN |

·Only cells of the nervous system (i.e., neuronal population and glial cells) at a mature stage ·All species |

|

OUT |

All except those included |

|

|

Exposure |

IN |

·Identified stressors (Objective 2) ·The exposure must occur during the mature stage |

|

OUT |

·Chemical mixture ·Less than one control and three concentrations tested |

|

|

Endpoints |

IN |

·ETC inhibition ·Mitochondrial dysfunction (i.e., oxygen consumption rate, mitochondrial membrane potential, elevated reactive oxygen species, mitochondrial oxidative damage) ·Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons |

In vivo studies

|

Study design |

IN |

Any |

|

OUT |

None |

|

|

Population |

IN |

Mammals and zebrafish |

|

OUT |

All except those included |

|

|

Exposure |

IN |

·Identified stressors. ·The exposure must occur in adults. |

|

OUT |

·In-uterus, developmental stage. ·Mixtures. ·Less than one control and two concentrations tested |

|

|

Endpoints |

IN |

·Labeling of dopaminergic neurons by fluorescent dopamine analogs, or genetically labeled dopaminergic neurons (e.g., GFP expression under control of TH promoter). ·Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons ·Motor deficits |

To develop the empirical evidence, chemicals listed in Delp 2019 and Delp 2021 were considered. In addition, for compounds that were identified or measured as cIII inhibitor, data were extracted from Bennekou (2020), van der Stel, W. (2021) and Van der Stel et al., 2022. Endpoints and assays were selected on their relevance to AOP 3 and the use of appropriate cell models (i.e., neuronal cells and HepG2 for KE1542, neuronal cells only for KE177 and KE890). Further details are provided in the KE section “How it is measured” and in the empirical evidence for the KER.

Quantitative understanding of the KERs was gained by modelling the KERs within the qAOP framework and methods that were developed in Tebby et al. (2022) and further developed during the negotiated procedure with EFSA (Reference: NP/EFSA/PREV/2024/02). A set of compounds used for AOP quantification was selected based on availability of multiple-concentration data representing at least two identical adjacent KEs. Equations representing the KERs were selected based on the dose-response data for adjacent KEs. These equations were parameterized using a bayesian framework, which allowed completing data gaps for cIII inhibition with prior knowledge on cI inhibition.

Summary of the AOP

Events:

Molecular Initiating Events (MIE)

Key Events (KE)

Adverse Outcomes (AO)

| Type | Event ID | Title | Short name |

|---|

| MIE | 1542 | Inhibition, Mitochondrial complex III | Inhibition, Mitochondrial complex III |

| KE | 177 | Increase, Mitochondrial dysfunction | Increase, Mitochondrial dysfunction |

| KE | 890 | Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway | Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway |

| AO | 896 | Parkinsonian motor deficits | Parkinsonian motor deficits |

Relationships Between Two Key Events (Including MIEs and AOs)

| Title | Adjacency | Evidence | Quantitative Understanding |

|---|

Network View

Prototypical Stressors

| Name |

|---|

| Antimycin A |

| Picoxystrobin |

Life Stage Applicability

| Life stage | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Adult | High |

Taxonomic Applicability

Sex Applicability

| Sex | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Male | High |

| Female | High |

Overall Assessment of the AOP

Assessing confidence in the overall AOP depends on the biological plausibility of the pathway, the evidence for the essentiality of the Key Events (KEs), the empirical evidence supporting it and the quantitative understanding of the KERs. The table below summarizes the overall weight of evidence, based on evaluations of individual linkages provided in the KERs.

|

MIE/KE1542 Inhibition of cIII |

KE177 Mitochondrial dysfunction |

KE890 Degeneration of DA neurons of nigrostriatal pathway |

|

|

Essentiality of KEs |

Strong |

Strong |

Strong |

|

KER 3637 Inhibition, cIII leads to mitochondria dysfunction

|

KER 908 Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway |

KER 910 Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway leads to Parkinsonian motor deficits |

|

|

Biological plausibility |

Strong |

Strong |

Strong |

|

Empirical evidence |

Strong |

Moderate to Strong |

Weak |

Domain of Applicability

This AOP has is not limited by sex or specific life stages. However, aging may enhance the progression of the pathway, and sex -related differences in mitochondrial function have been reported. The potential relevance of this AOP during developmental stages has not been investigated. No species-specific limitations have been identified. The AOP is mainly supported by data derived from human cells representative of dopaminergic neurons. When available, rodents is the species most commonly used in studies with chemical stressors, although experimental studies using alternative species (e.g. Drosophila melanogaster) have been also performed.

Essentiality of the Key Events

Human mutations of cIII and proof of concept in cellular and animal models.

The essentiality of the KEs is strong, based on observations of human mutations whose expression in animal models leads to dysfunction and deterioration of dopaminergic neurons, together with the occurrence of motor deficits.

A four-base-pair deletion in the mitochondrial gene that encodes cytochrome b has been described in patients with early-onset parkinsonism (De Coo et al., 1999). High levels of this mutation in a cell line homoplastic for the patient’s wild-type mtDNA were associated with a marked defect in the assembly and function of complex III with the Rieske protein and subunit VI, increased ROS formation and reduced UQCRC1 levels, as well as a dramatic loss of complex I activity. This suggests that a fully assembled complex III is necessary for the stabilisation and functioning of complex I (Rana et al. 2000, Acin-Perez et al. 2004).

In a study performed by Lin et al. (2020), whole exome sequencing was conducted on a Taiwanese family with multiple cases of Parkinson’s disease and polyneuropathy across three consecutive generations. This analysis revealed a pathogenic variant in the UQCRC1 gene, resulting in the p.Tyr314Ser mutation. Two additional unrelated families were reported to carry UQCRC1 mutations, including the p.Ile311Leu mutation and a combination of splicing mutations and frameshift mutations. These mutations were absent in control populations. Affected carriers displayed classic symptoms of Parkinson's disease, including asymmetric tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and progressive motor deficits. All patients responded well to levodopa treatment. Additionally, patients exhibited signs of sensorimotor neuropathy, including distal muscle atrophy, absent reflexes and marked nerve conduction deficits indicative of axonal degeneration. The pathogenicity of the identified mutations was investigated using knock-in SH-SY5Y, Drosophila, and mouse models. SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells expressing either the UQCRC1 p.Tyr314Ser or p.Ile311Leu mutation displayed shortened neurites, mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction, reduced complex III activity and ATP production, and increased reactive oxygen species production. Drosophila expressing the mutant UQCRC1 p.Tyr314Ser exhibited age-dependent locomotor defects and a loss of dopaminergic neurons (TH-positive). Heterozygous UQCRC1 p.Tyr314Ser knock-in mice exhibited progressive, age-dependent deficits in motor behaviour, including reduced walking stride length and speed, which mimicked human PD gait disturbances. Dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (SNc) were progressively lost from 9 months of age onwards, accompanied by reduced 18F-DOPA uptake and lower dopamine levels in the striatum. Ultrastructural analysis of nigral neurons revealed mitochondrial abnormalities. Levodopa administration significantly reversed motor dysfunction in knock-in mice, highlighting the importance of dopaminergic depletion in the disease mechanism.

Loss-of-function mutations in the TTC19 gene, which encodes the tetratricopeptide repeat domain 19 protein, have been associated with mitochondrial complex III deficiency and severe neurological symptoms. By six months of age, mice lacking this gene displayed neurological abnormalities, including an atypical feet-clasping reflex, as well as impaired motor coordination, exploratory behaviour, proprioception and motor planning. Their motor endurance was also significantly reduced. In terms of overall activity, both male and female Ttc19-deficient mice showed a substantial reduction in total movement, ambulatory activity and rearing behaviour. No structural abnormalities were observed in skeletal muscle, and whole brain sagittal sections from six-month-old mice revealed no evidence of neuronal loss, neurodegeneration, or apoptosis, as assessed by Nissl, Fluoro-Jade C, and TUNEL staining, respectively. However, it is important to note that dopaminergic neurons were not examined specifically in this study (Bottani et al. 2017).

|

Support for essentiality of KEs – additional observations |

||||

|

MIE/KE1542 Inhibition of cIII |

Strong |

See UQCRC1 and TTC19 mutations |

||

|

KE177 Mitochondrial dysfunction |

Strong |

The overexpression of paraoxonase 2 (PON2), an antioxidant enzyme that is primarily found in the inner mitochondrial membrane, reduces the generation of superoxide in the mitochondria induced by antimycin (Altenhöfer et al., 2010; Devarajan et al., 2011). The activation of methionine sulfoxide reductase A, a ley mitochondrial-localised endogenous antioxidan enzyme, with substrates like S-methy-L-cysteine, reduces antimycin A-induced superoxide generation and mitochondrial membrane potential depolarisation (Ni et al. 2020). This provide indirect evidence for essentiality in KE 890, being oxidative damage considered a mechanism of pathogenic significance (Zhou 2008). |

||

|

KE890 Degeneration of DA neurons of nigrostriatal pathway |

Strong |

Rationale: Clinical and experimental evidences show that the pharmacological replacement of the dopamine (DA) neurofunction by allografting fetal ventral mesencephalic tissues is successfully replacing degenerated DA neurons resulting in the total reversibility of motor deficit in animal model and partial effect is observed in human patient for PD (Widner et al., 1992; Henderson et al., 1991; Lopez-Lozano et al., 1991; Freed et al., 1990; Peschanski et al., 1994; Spencer et al., 1992). Also, administration of L-DOPA or DA agonists results in an improvement of motor deficits (Calne et al 1970; Fornai et al. 2005). The success of these therapies in man as well as in experimental animal models clearly confirms the causal role of dopamine depletion for PD motor symptoms ( Connolly et al., 2014; Lang et al., 1998; Silva et al., 1997; Cotzias et al., 1969; Uitti et al., 1996; Ferrari-Toninelli et al., 2008; Kelly et al., 1987; Walter et al., 2004; Narabayashi et al., 1984; Matsumoto et al., 1976; De Bie et al., 1999; Uitti et al., 1997; Scott et al., 1998; Moldovan et al., 2015; Deuschl et al., 2006; Fasano et al., 2010; Castrioto et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2014; Widner et al., 1992; Henderson et al., 1991; Lopez-Lozano et al., 1991; Freed et al., 1990; Peschanski et al., 1994; Spencer et al., 1992). Furthermore, experimental evidence from animal models of PD and from in-vitro systems indicate that prevention of apoptosis through ablation of BCL-2 family genes prevents or attenuates neurodegeneration of DA neurons (Offen D et al., 1996; Dietz GPH et al. 2008). |

||

Uncertainties and Inconsistencies

UQCRC1 mutations are rare and may primarily affect specific populations, warranting further studies in different ethnic cohorts to establish prevalence (Lin et al. 2020). Post-mortem brain tissues were unavailable to confirm findings from mouse models in human patients. Additionally, other studies have explored the potential role of UQCRC1 mutations in Parkinson’s disease (PD), yielding mixed results. Several studies failed to replicate the association between UQCRC1 and PD in the Chinese mainland population (Lin et al. 2020b; Zhao et al. 2021; Liao et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2024) and Europeans (Senkevich et al. 2021; Courtin et al. 2021). To overcome the small sample size (107 to 3274) and the focus on PD patients cohort of the previous studies, Jing et al. (2025) provided population-level support for UQCRC1 involvement in PD through a large-scale UK Biobank analysis (including over 500,000 participants), identifying a significant association between protein-truncating variants in UQCRC1 and increased PD risk (OR = 6.59, p = 1.20 × 10⁻⁶).

Mutations affecting cIII may be associated with additional pathological conditions that contribute to or exacerbate motor dysfunction. For example, polyneuropathy, reported in patients carrying UQCRC1 mutations and corresponding experimental models (Lin et al., 2020), can intensify motor impairment. Additionally, impaired neuromuscular junction morphology and peripheral nerve degeneration were evident in Drosophila expressing the mutant UQCRC1 p.Tyr314Ser, while peripheral neuropathy was evident in UQCRC1 p.Tyr314Ser knock-in mice, with reduced sciatic nerve conduction amplitudes and morphological changes in myelinated fibres consistent with the phenotypes seen in humans carrying the mutation (Lin et al., 2020).

Evidence Assessment

Concordance of concentration-response relationship

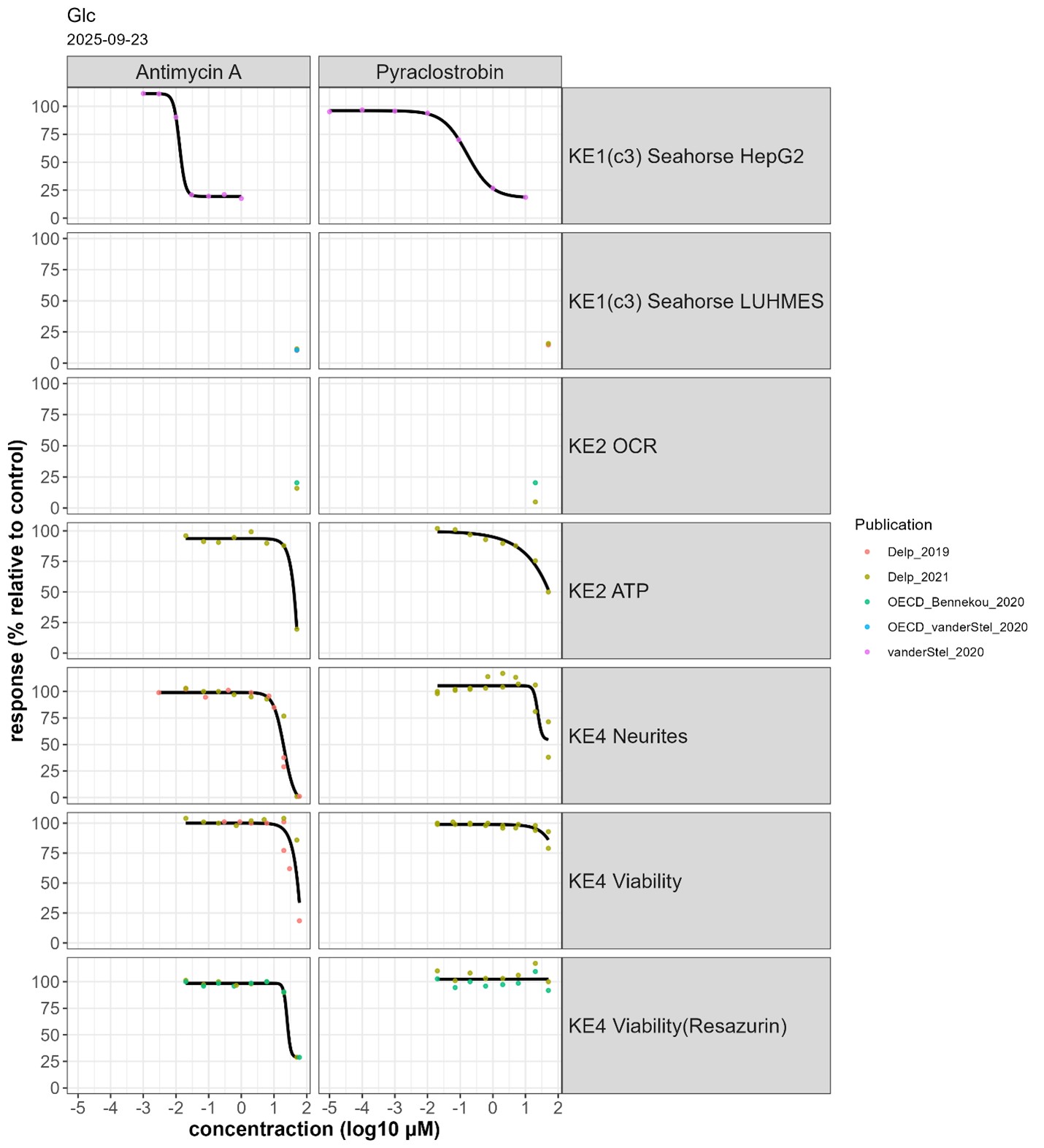

Concentration-response data for the prototypical stressors Antimycin A and Pyraclostrobin has been derived from Delp et al. 2019, 2021, Bennekou-OECD 2020, van der Stel-OECD 2020, van der Stel et al. 2020 (Fig. 1). Data points were extracted manually from graphs using PlotDigitizer (v3.0.0). The curve fits were generated using the L.4 function from the drc package in R and organised across KEs to facilitate the analysis of the concordance of the concentration-response relationship. The different KEs have been measured in vitro, no in vivo data were retrieved from the literature search.

Fig. 1 Concentration-response of Antimycin A and Pyraclostrobin across 7 endpoints in glucose medium

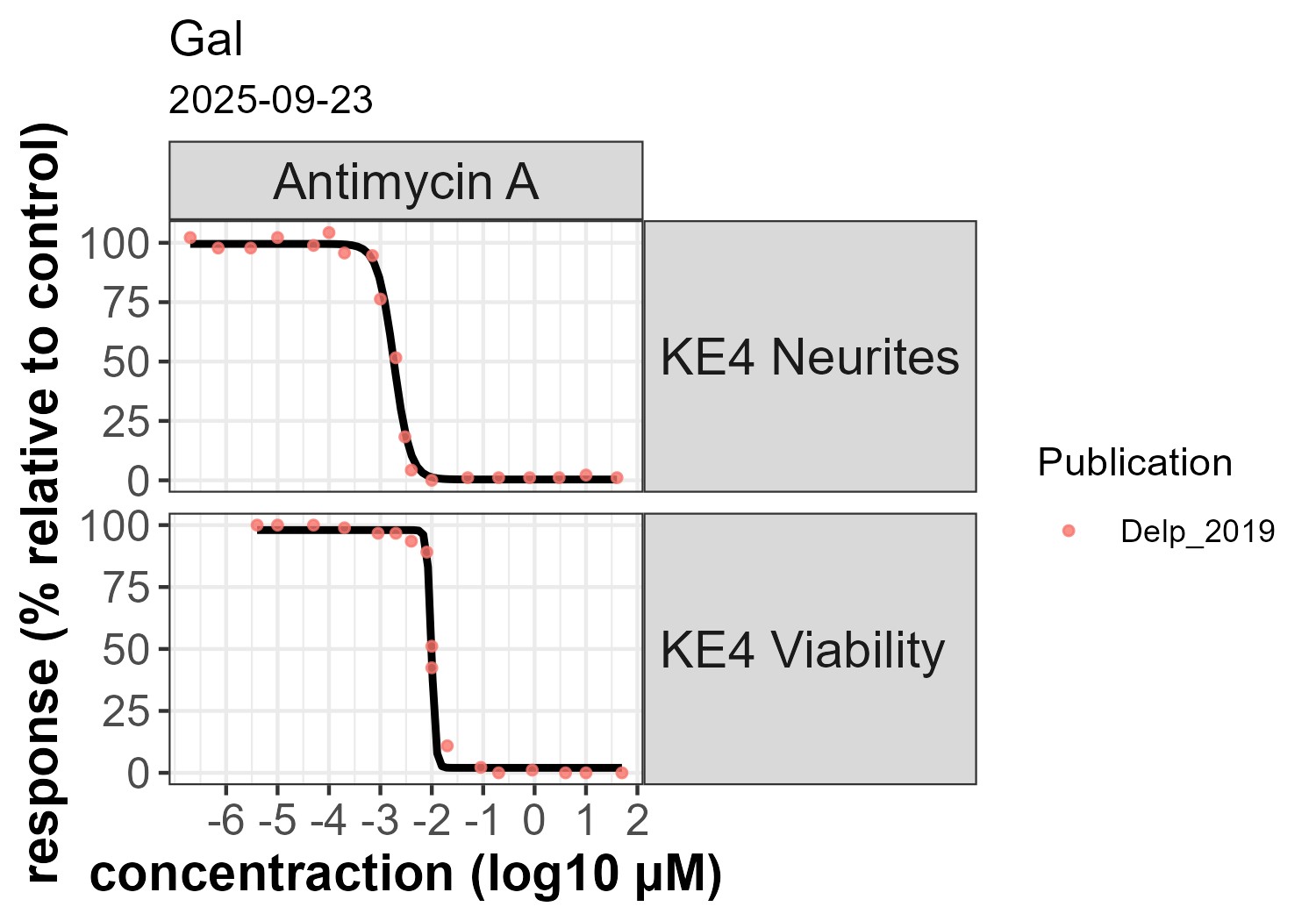

Fig 2. KE 890: Concentration-response of Antimycin A in galactose medium

Antimycin A and Pyraclostrobin were evaluated across 7 endpoints corresponding to three KEs in glucose containing medium (Fig. 1). Antimicyn A was additionally tested in galactose containing medium, but only for KE 890 (fig. 2) In glucose medium, Antimycin A had an EC50 of 19 nM for MIE/KE1542 in permeabilised HepG2, with maximal inhibition starting at ~ 30 nM. MIE/KE 1542 was tested at a single concentration (50 µM) in permeabilised LUHMES cells (fig. 1). Thus, the concentration-response inhibition for cIII in permeabilised HepG2 cells was considered as representative for LUHMES cells to evaluate concentration concordance across events.

KE 177 and KE 890 were only affected at concentrations > 10 µM when using glucose-containing medium (fig. 1). In galactose-containing medium, KE 890 reached maximal inhibition at about ~ 30 nM, in line with the effect for MIE/KE 1542 (Fig. 2).

The observed difference between the glucose and galactose conditions is due to the ability of cells to switch from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis for energy production in the presence of glucose, compensating for mitochondrial inhibition. Substituting glucose with galactose forces cells to rely predominantly on mitochondria for energy production, thereby strenghtening the functional relationship between MIE/KE 1542 and downstream KEs (Marroquin et al. 2007; Swiss et al. 2011, Delp et al. 2019; Delp et al. 2021).

For Pyraclostrobin, MIE/KE 1542 measured in permeabilised HepG2 (EC50 400 nM) was maximally inhibited at 10 µM (Fig. 1). Downstream KEs were affected at slightly higher concentrations. However, at 50 µM, the highest tested concentration, no significant loss of viability was detectable (Fig. 1).

Other strobilurins (i.e. Azoxystrobin and Pyraclostrobin) have similar effects, but with slightly lower potency (see “Quantitative understanding of the linkage” in KER 3637).

Data from experiments using the stressors antimycin A and pyraclostrobin show concordance in concentrations-response relationships across key events (KEs). Antimycin A exhibited high potency for CIII inhibition (MIE/KE1542) leading to neurodegeneration. Pyraclostrobin produced downstream effects less efficiently and without overt cytotoxicity, likely due to the limited 24-hour exposure, highlighting the need for time-course evaluations. The absence of galactose-based data introduces significant uncertainty, as glucose-rich conditions likely underestimate mitochondrial vulnerability. A no-effect level could not be determined because concentration-response data were lacking for endpoints directly reflecting mitochondrial dysfunction, such as oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP).

Summary of quantitative effects at the concentration of cIII inhibitors triggering the AO

|

Concentration |

MIE/KE 1542 cIII inhibition |

KE 177 Mitochondrial dysfunction |

KE 890 Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway |

||

|

Antimycin A |

100 nM |

Glucose |

80% reduction in OCR in HepG2 |

no reduction in ATP |

no reduction in viability or neurites |

|

Galactose |

- |

- |

100% loss of neurites + viability |

||

|

60 µM |

Glucose |

90% reduction in OCR in LUHMES 80% reduction in OCR in HepG2 |

75% reduction of ATP 75% reduction in OCR |

100% loss of neurites > 50% loss of viability |

|

|

Galactose |

- |

100% loss of neurites + viability |

|||

|

Pyraclostrobin |

10 µM |

Glucose |

80% reduction in OCR in HepG2 |

no reduction of ATP |

no reduction in viability or neurites |

|

50 µM |

80% reduction in OCR in HepG2 85% reduction in OCR in LUHMES |

75% reduction of OCR 50% reduction of ATP |

50% loss of neurites ~20% loss of viability |

Temporal concordance across the AOP

OCR reduction (KE1542) is effective within within seconds and changes in MMP (KE177) can be detected within minutes. Time concordance could not be evaluated across KEs 177 and 890 since measurements were available at a single time point (24 h).

Uncertainties and inconsistencies table

|

Uncertainty |

Impact |

Reason |

|

KE 1542 measured in permeabilised cells |

Permeabilisation provides direct access for the tested compounds and substrates to the mitochondria and respiratory chain components. The physicochemical properties of the tested compound may reduce its ability to permeate the plasma membrane of intact cells, thus reducing or preventing its uptake which could affect the concentration and the time required to impact the downstream KEs. |

|

|

Lack of data in galactose condition |

High |

In vitro cell models in general are characterized by an unphysiological reliance on glycolysis. In the presence of glucose any KE is influenced by the contribution of oxidative phosphorylation in addition to glycolisis to meet the cellular need for ATP. Thus, the KEs are influenced by the glycolisis rate. Glucose concentrations in culture medium higher than the physiological level enhances cellular resistance to mitochondrial dysfunction. Application of galactose instead of glucose in the medium allows a shift towards mitochondrial ATP generation. Even under these conditions, glycolysis significantly contributes to ATP production. |

|

Use of HepG2 concentration response curves related to the measurement of oxygen consumption upon inhibition of cIII as a surrogate to represent inhibition of cIII in LUHMES cells, due to the lack of concentration response data for LUHMES cells |

Low |

It is assumed that since the exposure is acute and in permeabilized cells, the test chemical would have immediate access to the mitochondria. Other mechanisms such as transport into the cells or an indirect effect via other signaling pathways were considered negligible under these assay conditions. |

|

Brain vs liver mitochondria |

A study by Balmaceda et al. (2024) in isolated mitochondria provides evidence for intrinsic bioenergetic differences between brain and liver mitochondria obtained from mice, highlighting tissue-specific substrate preferences, redox states, and sensitivity to electron transport system (ETS) deficiencies. Their findings demonstrate that brain mitochondria rely more heavily on Complex I (CI) substrates and exhibit greater vulnerability to CI and Complex III (CIII) dysfunction, whereas liver mitochondria preferentially utilize Complex II (CII) substrates and show metabolic resilience (Balmaceda et al., 2024). These observations are supported by Lesner et al. (2022), who reported that CI is dispensable in liver but essential in brain tissue, and by Szibor et al. (2020), who confirmed higher ROS production in brain mitochondria under reverse electron transport (RET) conditions. Additionally, Rossignol et al. (1999, 2000) emphasized tissue-specific thresholds in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) control. By contrast, Gusdon et al. (2015) observed similar ETC enzyme activities in mitochondria from different tissues. However, they also confirmed a greater tendency for ROS production in brain mitochondria. This suggests that functional outcomes may be more dependent on systemic or regulatory factors than on the intrinsic properties of mitochondria. The differing results regarding the electron transport system may be due to the higher methodological resolution employed by Balmaceda et al. (2024), which included high-resolution respirometry and real-time coenzyme Q redox monitoring rather than bulk measurements of enzymatic activity and substrate transport. This approach permitted a more detailed and mechanistic understanding of ETS sensitivity and tissue-specific mitochondrial function. Additional factors that can contribute to tissue-specific differences are mtDNA heteroplasmy and lineage-specific transcriptional networks established during development (Burr et al. 2023). |

|

|

no concentration-response data for OCR in LUHMES |

High |

Increase the uncertainty in the concordance concentration response relationship across the KEs |

|

Exposure is limited in concentrations and to 24 h |

High |

It is possible that the effects on KE1542 and KE177 occur with higher potency or occur more rapidly than those required to observe an effect on KE890. The loss of temporal resolution may determine an excessive steepness of the dose–response curve. Indeed, for all strobilurins, the effects are starting close to the highest tested concentration |

|

Neurite outgrowth assays (NA) |

Medium |

Typically conducted from DoD2 to DoD3. NA tested on differentiating neurons is not representative of an adult stage. Active molecular mechanisms that are no longer present in adult or differentiated cells are involved in development. A reduction in NA area may be due to the degeneration of neurites or interference with developing pathways. In this exposure scenario, it is unclear whether the chemical would lead to a loss of neurons, or only a delay in neurite outgrowth. A loss in neurite integrity in the absence of a loss of viability was not considered sufficient to indicate activation of KE 890. |

Weight of evidence (WoE)

The table provides an overall summary of the weight of evidence, based on evaluations of individual linkages from the 'Key Event Relationship' pages, with regard to biological plausibility.

|

Biological plausibility |

||

|

KER 3637 Inhibition, cIII leads to mitochondria dysfunction Direct |

Strong |

The mechanisms by which the inhibition of complex III leads to mitochondrial dysfunction are well understood, as described in the KER (Georgakopoulos et al. 2017; Cunatove and Fernandez-Vizarra 2024, Rugolo et al 2021) |

|

KER 908 Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway Direct |

Strong |

Mitochondrial are essential for ATP production, ROS management, calcium homeostasis and control of apoptosis. Mitochondrial homeostasis by mitophagy is also an essential process for cellular maintenance (Fujita et al. 2014). Because of their anatomical and physiological characteristics, SNpc DA neurons are considered more vulnerable than other neuronal populations (Sulzer et al. 2013; Surmeier et al.2010). Mechanistic evidence of mutated proteins relate the mitochondrial dysfunction in familial PD with reduced calcium capacity, increased ROS production, increase in mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and increase in cell vulnerability (Koopman et al. 2012; Gandhi et al. 2009). Human studies indicate mitochondrial dysfunction in human idiopathic PD cases in the substantia nigra (Keeney et al., 2006; Parker et al., 1989, 2008; Swerdlow et al., 1996). |

|

KER 910 Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway leads to Parkinsonian motor deficits Direct |

Strong |

The mechanistic understanding of the regulatory role of striatal DA in the extrapyramidal motor control system is well established. The loss of DA in the striatum is characteristic of all aetiologies of PD (Bernheimer et al. 1973). Characteristic motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, tremor, or rigidity are manifested when more than 80 % of striatal DA is depleted as a consequence of SNpc DA neuronal degeneration (Koller et al. 1992). |

Empirical support:

|

Empirical support |

||

|

KER 3637 Inhibition, cIII leads to mitochondria dysfunction Direct |

Strong |

A large body of research shows that inhibiting CIII results in mitochondrial dysfunction in a dose- and response-dependent manner (Delp et al. 2021; Delp et al. 2019; Bennekou et al.-OECD 2020). |

|

KER 908 Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway Direct |

Moderate to strong |

Most findings on cIII inhibitors, come from in in vitro studies using cell models representative of dopaminergic neurons such as LUHMES cells (Delp 2021, Delp 2019), SH-SY5Y (Killbride et al., 2021, Bir et al., 2014, Delp 2021). Ex-vivo experiments on rat brain slices showed that Antimycin exposure selectively reduced the proportion of substantia nigra neurons and their dendrites. Neuronal death appears underestimated in glucose-containing media but markedly increases when glucose is replaced with galactose, likely due to the loss of glycolysis as a compensatory pathway.

|

|

KER 910 Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway leads to Parkinsonian motor deficits Direct |

Low |

Currently, no in vivo evidence links cIII inhibitors to the development of Parkinsonian motor deficits. Existing data are limited to observations in Parkinson’s disease patients carrying mutations in cIII subunits, which lead to reduced enzymatic activity (Rana et al. 2000; Lin et al. 2020; Jing et al. 2025) |

Known Modulating Factors

| Modulating Factor (MF) | Influence or Outcome | KER(s) involved |

|---|---|---|

| Paraoxonase 2 | Prevents mitochondrial dysfunction | KER3637: Inhibition, Mitochondrial complex III leads to Mitochondrial dysfunction |

| Mitochondrial Cu superoxide dismutase | Prevents mitochondrial dysfunction | KER3637: Inhibition, Mitochondrial complex III leads to Mitochondrial dysfunction |

| Mitochondrial Zn superoxide dismutase | Prevents mitochondrial dysfunction | KER3637: Inhibition, Mitochondrial complex III leads to Mitochondrial dysfunction |

Quantitative Understanding

Quantification was considered based on the methods for quantitative AOPs published in Tebby et al. (2022). Data used to gain quantitative understanding was obtained for a set of four compounds, antimycin A, azoxystrobin, picoxystrobin and pyraclostrobin. Single-concentration data for cIII inhibition (MIE/KE1542) at 30 minutes was collected by digitalising figures from Delp et al. (2019). Multiple concentration data was collected from Biostudies S-TOXR1683 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/eu-toxrisk/studies/S-TOXR1683) for ATP content (KE177) measured at 24 hours in LUHMES cells. Multiple concentration data was collected from Biostudies S-TOXR1203 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/eu-toxrisk/studies/S-TOXR1203) for cell viability and neurite area (KE890) measured at 24 hours in LUHMES cells. Both Biostudies datasets appeared to have been published in Delp et al. (2021).

The readouts that were available displayed decreasing levels of effect downstream the AOP.

CIII inhibition in LUHMES cells by antimycin A, pyraclostrobin, picoxystrobin was measured in single concentration assays; concentration-response modelling of this data requires prior information on the slope, extrapolated from other datasets, which could be obtained for cI inhibition or in HepG2 cells. Endpoints measured in similar assays are preferred since they allow for comparable exposure concentrations, therefore quantification was limited to data obtained in LUHMES cells. No data on mitochondrial respiration or dysfunction in LUHMES cells was available for the identified cIII stressors.

Antimycin A, azoxystrobin, picoxystrobin and pyraclostrobin lack data demonstrating significant effects on KE1542 at concentrations under 50µM in LUHMES cells. If low potency of the cIII inhibitors at the MIE/KE1 is confirmed, this could explain that KE177 and KE890 were only triggered to a small extent in particular for azoxystrobin and picoxystrobin, implying large uncertainty when KE890 was predicted based on KE177. Low potency at KE177 and KE890 could also be explained by the ability of cells to switch from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis for energy production in the presence of glucose, compensating for mitochondrial inhibition.

Each KE can be represented by several readouts; reassessment of the qAOP for cI inhibition from Tebby et al. (2022) highlighted the following limitations regarding the choice of endpoints representing the KEs and regarding the KER between the MIE (here cIII inhibition) and the first KE. Although fewer data is available for cIII stressors than for cI stressors, these limitations form the basis of the recommendations for further data collection.

Neuron degeneration may not be adequately represented by neurite area measured in differentiating LUHMES cells during a 24-hour exposure starting a day 2 of differentiation. Repeated exposure over a period longer than 24h in differentiated cells should be investigated to identify potential effects on KE890 and a shorter exposure time of less than 24 hours for KE177.

Antimycin A and pyraclostrobin caused a decrease in neurite area and in cell viability at high concentrations levels, resulting in incomplete concentration response curves in medium containing glucose and high uncertainty regarding potency in terms of EC25 or EC50.

Several measurements of KE 177 are possible: the decrease in ATP production could be an alternative endpoint to the decrease in mitochondrial respiration. Data on the resulting decrease in ATP content was available and was envisioned as a measurement of a downstream key event of mitochondrial respiration. Dose-response data available in the literature had been mostly obtained in assays using glucose as a substrate rather than galactose. More data is needed to quantify the KERs using data obtained in galactose conditions; the PANDORA project (OC/EFSA/PREV/2023/0, Environmental Neurotoxicants – Advancing Understanding on the Impact of Chemical Exposure on Brain Health and Disease, LOT 3) is currently producing such data.

Endpoints measured in the same experimental setup allow for comparisons of effective concentrations along the AOP. Complex III inhibition was measured in permeabilized cells, whereas the other endpoints that were quantitatively assessed were measured in intact cells. Intracellular exposure concentrations are therefore likely different and dependent on toxicokinetics. Chemical agnosticity of the quantitative KER between complex III inhibition and downstream KEs cannot be expected. Since the concentration levels in both assays may not be directly comparable due to differences in toxicokinetics, lack of overlap would not suggest a missing intermediate key event. Measuring OCR in intact cells, which are currently lacking, would help to lower this uncertainty. Without intracellular concentration data, the comparison of effective concentrations in dissimilar assays provides only limited quantitative understanding of the KER.

When exposure concentrations between adjacent KEs are comparable, quantitative AOP modelling would benefit from application of FAIR principles to data. Publication of raw data with metadata that could indicate which data were obtained with identical biological material and experimental conditions would help refine quantitative KERs.

Overall, reassessment of the available data for cIII inhibition considering the preliminary qAOP developed for cI inhibition by Tebby et al. (2022) highlighted several limitations inherent to the data used for qAOPs, in particular comparability of exposure concentrations between the various endpoints, comparability and relevance of timepoints and exposure durations, the necessary overlap in effective concentrations between adjacent endpoints that are measured at comparable exposure concentrations and relevant timepoints, and data reproducibility. Selection of most relevant readouts and accurate characterization of the molecular initiating event for cross-validation are critical when designing in vitro experiments targeted at calibrating qAOPs.

Considerations for Potential Applications of the AOP (optional)

This project has been sponsored by EFSA (Reference: NP/EFSA/PREV/2024/02). An AOP (AOP 3) informed IATA case study base on mitochondrial complex I inhibitor has been published by EFSA and will be used in the regulatory risk assessment by the Authority.

EFSA has an ongoing project for testing pesticides expected to interact with the mitochondrial electron transport chain using a testing battery covering the KEs included in the expanded AOP3. The proposed AOP will complement the AOP3 (by adding additional MIEs and newly produced empirical data). The additional MIE will converge at the KE mitochondrial dysfunction. There are currently no test guidelines for the assessment of mitochondrial toxicity or, more generally, to test for adult neurotoxicity including degenerative diseases like the parkinsonian syndrome. The implementation of the AOP 3 and the development of an AOP network having mitochondrial dysfunction as anchoring KE is intended to implement the ability of using NAMs to assess for neurotoxicity endpoints, including AO relevant for the parkinsonian syndrome. A testing battery is therefore proposed to describe most of the KEs included in the network, identified MIE and using dopaminergic cells of human derivation for testing intermediate KEs or the in-vitro AO (dopaminergic cell toxicity and loss). Currently, the in vitro AO is expected to act as surrogate of the proposed AO (Parkinsonian motor deficits); though, it is expected that the AOP will be further implemented with inclusion of alternative animal models like the zebrafish for assessing the motor dysfunction consequent to the loss of dopaminergic neurons. The basis of this approach is to use the AOP3 network to define a relevant point-of-departure (PoD) for risk assessment, to convert this PoD by an in vitro-to-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) to a threshold dose, and to use this to define acceptable daily intakes (ADI) or similar threshold measures.

References

Acín-Pérez R, Bayona-Bafaluy MP, Fernández-Silva P, Moreno-Loshuertos R, Pérez-Martos A, Bruno C, Moraes CT, Enríquez JA. Respiratory complex III is required to maintain complex I in mammalian mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2004 Mar 26;13(6):805-15. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00124-8.

Altenhöfer S, Witte I, Teiber JF, Wilgenbus P, Pautz A, Li H, Daiber A, Witan H, Clement AM, Förstermann U, Horke S. One enzyme, two functions: PON2 prevents mitochondrial superoxide formation and apoptosis independent from its lactonase activity. J Biol Chem. 2010 Aug 6;285(32):24398-403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.118604. Epub 2010 Jun 8. PMID: 20530481; PMCID: PMC2915675.

Balmaceda, V., Komlódi, T., Szibor, M., Gnaiger, E., Moore, A. L., Fernandez-Vizarra, E., & Viscomi, C. (2024). The striking differences in the bioenergetics of brain and liver mitochondria are enhanced in mitochondrial disease. BBA - Molecular Basis of Disease, 1870, 167033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2024.167033

Bennekou, S. H., van der Stel, W., Carta, G., Eakins, J., Delp, J., Forsby, A., Kamp, H., Gardner, I., Zdradil, B., Pastor, M., Gomes, J. C., White, A., Steger-Hartmann, T., Danen, E. H. J., Leist, M., Walker, P., Jennings, P., & van de Water, B. (2020).ENV/JM/MONO(2020)23 Case study on the use of integrated approaches to testing and assessment for mitochondrial complex-iii-mediated neurotoxicity of azoxystrobin - read-across to other strobilurins: Series on testing and assessment no. 327. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Bernheimer H, Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O, Jellinger K, Seitelberger F. Brain dopamine and the syndromes of Parkinson and Huntington. Clinical, morphological and neurochemical correlations. J Neurol Sci. 1973 Dec;20(4):415-55

Bir A, Sen O, Anand S, Khemka VK, Banerjee P, Cappai R, Sahoo A, Chakrabarti S. α-Synuclein-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in isolated preparation and intact cells: implications in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 2014 Dec;131(6):868-77. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12966. Epub 2014 Nov 18. PMID: 25319443.

Bottani E, Cerutti R, Harbour ME, Ravaglia S, Dogan SA, Giordano C, Fearnley IM, D'Amati G, Viscomi C, Fernandez-Vizarra E, Zeviani M. TTC19 Plays a Husbandry Role on UQCRFS1 Turnover in the Biogenesis of Mitochondrial Respiratory Complex III. Mol Cell. 2017 Jul 6;67(1):96-105.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.001. Epub 2017 Jun 29. PMID: 28673544.

Burr, S. P., Klimm, F., Glynos, A., Prater, M., Sendon, P., Nash, P., … & Chinnery, P. F. (2023). Cell lineage-specific mitochondrial resilience during mammalian organogenesis. Cell, 186(6), 1212–1229.e21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.034

Calne DB (1970) L-Dopa in the treatment of parkinsonism. Clin Pharmacol Ther 11(6):789–801

Castrioto A, Lozano AM, Poon YY, Lang AE, Fallis M, Moro E. 2011. Ten-year outcome of subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson disease: a blinded evaluation. Arch Neurol. 68(12):1550-6.

Connolly BS, Lang AE. Pharmacological Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Review. JAMA. 2014;311(16):1670–1683. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3654

Cotzias, George C., Paul S. Papavasiliou, and Rosemary Gellene. "Modification of Parkinsonism—chronic treatment with L-dopa." New England Journal of Medicine 280.7 (1969): 337-345.

Courtin, T., Tesson, C., Corvol, JC. et al. Lack of evidence for association of UQCRC1 with autosomal dominant Parkinson's disease in Caucasian families . Neurogenetics 22, 365–366 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10048-021-00647-4

Čunátová K and Fernández-Vizarra E. Pathological variants in nuclear genes causing mitochondrial complex III deficiency: An update. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2024 Nov;47(6):1278-1291. doi: 10.1002/jimd.12751

de Bie, R. M., de Haan, R. J., Nijssen, P. C., Rutgers, A. W. F., Beute, G. N., Bosch, D. A., ... & Speelman, J. D. (1999). Unilateral pallidotomy in Parkinson's disease: a randomised, single-blind, multicentre trial. The Lancet, 354(9191), 1665-1669.

De Coo IF, Renier WO, Ruitenbeek W, Ter Laak HJ, Bakker M, Schägger H, Van Oost BA, Smeets HJ. A 4-base pair deletion in the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene associated with parkinsonism/MELAS overlap syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1999 Jan;45(1):130-3. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199901)45:1<130::aid-art21>3.3.co;2-q. PMID: 9894888.

Delp J, Cediel-Ulloa A, Suciu I, Kranaster P, van Vugt-Lussenburg BM, Munic Kos V, van der Stel W, Carta G, Bennekou SH, Jennings P, van de Water B, Forsby A, Leist M. Neurotoxicity and underlying cellular changes of 21 mitochondrial respiratory chain inhibitors. Arch Toxicol. 2021 Feb;95(2):591-615. doi: 10.1007/s00204-020-02970-5. Epub 2021 Jan 29. PMID: 33512557; PMCID: PMC7870626.

Delp J, Funke M, Rudolf F, Cediel A, Bennekou SH, van der Stel W, Carta G, Jennings P, Toma C, Gardner I, van de Water B, Forsby A, Leist M. Development of a neurotoxicity assay that is tuned to detect mitochondrial toxicants. Arch Toxicol. 2019 Jun;93(6):1585-1608. doi: 10.1007/s00204-019-02473-y. Epub 2019 Jun 12. PMID: 31190196.

Deuschl, G., Schade-Brittinger, C., Krack, P., Volkmann, J., Schäfer, H., Bötzel, K., ... & Voges, J. (2006). A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 355(9), 896-908.

Devarajan A, Bourquard N, Hama S, Navab M, Grijalva VR, Morvardi S, Clarke CF, Vergnes L, Reue K, Teiber JF, Reddy ST. Paraoxonase 2 deficiency alters mitochondrial function and exacerbates the development of atherosclerosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011 Feb 1;14(3):341-51. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3430. Epub 2010 Sep 6. PMID: 20578959; PMCID: PMC3011913.

Dietz GPH, Stockhausen KV, Dietz B et al. (2008) Membrane-permeable Bcl-xL prevents MPTP-induced dopaminergic neuronal loss in the substantia nigra. J Neurochem 104:757-765. Doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05028.

EFSA Panel on Plant Protection Products and their residues (PPR); Ockleford C, Adriaanse P, Berny P, Brock T, Duquesne S, Grilli S, Hernandez-Jerez AF, Bennekou SH, Klein M, Kuhl T, Laskowski R, Machera K, Pelkonen O, Pieper S, Smith R, Stemmer M, Sundh I, Teodorovic I, Tiktak A, Topping CJ, Wolterink G, Angeli K, Fritsche E, Hernandez-Jerez AF, Leist M, Mantovani A, Menendez P, Pelkonen O, Price A, Viviani B, Chiusolo A, Ruffo F, Terron A, Bennekou SH. Investigation into experimental toxicological properties of plant protection products having a potential link to Parkinson's disease and childhood leukaemia. EFSA J. 2017 Mar 16;15(3):e04691. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4691. PMID: 32625422; PMCID: PMC7233269.

Fasano, A., Romito, L. M., Daniele, A., Piano, C., Zinno, M., Bentivoglio, A. R., & Albanese, A. (2010). Motor and cognitive outcome in patients with Parkinson’s disease 8 years after subthalamic implants. Brain, 133(9), 2664-2676.

Ferrari-Toninelli G, Bonini SA, Cenini G, Maccarinelli G, Grilli M, Uberti D, Memo M. Dopamine receptor agonists for protection and repair in Parkinson's disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2008;8(12):1089-99. doi: 10.2174/156802608785161402. PMID: 18691134.

F. Fornai, O.M. Schlüter, P. Lenzi, M. Gesi, R. Ruffoli, M. Ferrucci, G. Lazzeri, C.L. Busceti, F. Pontarelli, G. Battaglia, A. Pellegrini, F. Nicoletti, S. Ruggieri, A. Paparelli, & T.C. Südhof, Parkinson-like syndrome induced by continuous MPTP infusion: Convergent roles of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and α-synuclein, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (9) 3413-3418, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0409713102 (2005).

Freed CR, Breeze RE, Rosenberg NL, Schneck SA, Wells TH, Barrett JN, Grafton ST, Huang SC, Eidelberg D, Rottenberg DA. Transplantation of human fetal dopamine cells for Parkinson's disease. Results at 1 year. Arch Neurol. 1990 May;47(5):505-12. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530050021007. PMID: 2334298.

Fujita KA, Ostaszewski M, Matsuoka Y, Ghosh S, Glaab E, Trefois C, Crespo I, Perumal TM, Jurkowski W, Antony PM, Diederich N, Buttini M, Kodama A, Satagopam VP, Eifes S, Del Sol A, Schneider R, Kitano H, Balling R. 2014. Integrating pathways of Parkinson's disease in a molecular interaction map. Mol Neurobiol.49(1):88-102.

Gandhi S, Wood-Kaczmar A, Yao Z, et al. PINK1-associated Parkinson’s disease is caused by neuronal vulnerability to calcium-induced cell death. Molecular Cell. 2009;33:627–638.

Georgakopoulos ND, Wells G, Campanella M. The pharmacological regulation of cellular mitophagy. Nat Chem Biol. 2017 Jan 19;13(2):136-146. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2287.

Gusdon, A. M., Zhu, J., Van Houten, B., & Chu, C. T. (2015). Respiration and substrate transport rates as well as reactive oxygen species production distinguish mitochondria from brain and liver. BMC Biochemistry, 16(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12858-015-0051-8

Henderson BT, Clough CG, Hughes RC, Hitchcock ER, Kenny BG. Implantation of human fetal ventral mesencephalon to the right caudate nucleus in advanced Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol. 1991 Aug;48(8):822-7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530200062020. PMID: 1898256.

Huang LS, Cobessi D, Tung EY, Berry EA. Binding of the respiratory chain inhibitor antimycin to the mitochondrial bc1 complex: a new crystal structure reveals an altered intramolecular hydrogen-bonding pattern. J Mol Biol. 2005 Aug 19;351(3):573-97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.053. PMID: 16024040; PMCID: PMC1482829.

Jing, X., Liu, Z., Li, W. et al. Protein-truncating variants in UQCRC1 are associated with Parkinson’s disease: evidence from half-million people. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 120 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-00987-0

Keeney PM,Xie J,Capaldi RA,Bennett JP Jr. (2006) Parkinson's disease brain mitochondrial complex I has oxidatively damaged subunits and is functionally impaired and misassembled. J Neurosci. 10;26(19):5256-64.

Kelly PJ, Ahlskog JE, Goerss SJ, Daube JR, Duffy JR, Kall BA. Computer-assisted stereotactic ventralis lateralis thalamotomy with microelectrode recording control in patients with Parkinson's disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987 Aug;62(8):655-64. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65215-x. PMID: 2439850.

Kilbride SM, Telford JE, Davey GP. Complex I Controls Mitochondrial and Plasma Membrane Potentials in Nerve Terminals. Neurochem Res. 2021 Jan;46(1):100-107. doi: 10.1007/s11064-020-02990-8. Epub 2020 Mar 4. PMID: 32130629.

Koller WC (1992) When does Parkinson's disease begin? Neurology. 42(4 Suppl 4):27-31 Koopman W, Hink M, Verkaart S, Visch H, Smeitink J, Willems P. 2007. Partial complex I inhibition decreases mitochondrial motility and increases matrix protein diffusion as revealed by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1767:940-947.

Koopman W, Willems P (2012) Monogenic mitochondrial disorders. New Engl J Med. 22;366(12):1132-41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1012478.

Lang, Anthony E., and Andres M. Lozano. "Parkinson's disease." New England Journal of Medicine 339.16 (1998): 1130-1143.

Lesner, N. P., Wang, X., Chen, Z., Frank, A., Menezes, C. J., House, S. D., … & Mishra, P. (2022). Differential requirements for mitochondrial electron transport chain components in the adult murine liver. eLife, 11, e80919. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.80919

Liao TW, Chao CY, Wu YR. UQCRC1 variants in early-onset and familial Parkinson's disease in a Taiwanese cohort. Front Neurol. 2022 Dec 9;13:1090406. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1090406. PMID: 36570444; PMCID: PMC9780373.

Lin CH, Tsai PI, Lin HY, Hattori N, Funayama M, Jeon B, Sato K, Abe K, Mukai Y, Takahashi Y, Li Y, Nishioka K, Yoshino H, Daida K, Chen ML, Cheng J, Huang CY, Tzeng SR, Wu YS, Lai HJ, Tsai HH, Yen RF, Lee NC, Lo WC, Hung YC, Chan CC, Ke YC, Chao CC, Hsieh ST, Farrer M, Wu RM. Mitochondrial UQCRC1 mutations cause autosomal dominant parkinsonism with polyneuropathy. Brain. 2020 Dec 5;143(11):3352-3373. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa279. PMID: 33141179; PMCID: PMC7719032.

Lin ZH, Zheng R, Ruan Y, Gao T, Jin CY, Xue NJ, Dong JX, Yan YP, Tian J, Pu JL, Zhang BR. The lack of association between ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase core protein I (UQCRC1) variants and Parkinson's disease in an eastern Chinese population. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2020 Sep;26(9):990-992. doi: 10.1111/cns.13436. Epub 2020 b Jul 14. PMID: 32666668; PMCID: PMC7415203.

Liu, Y., Li, W., Tan, C., Liu, X., Wang, X., Gui, Y., ... & Chen, L. (2014). Meta-analysis comparing deep brain stimulation of the globus pallidus and subthalamic nucleus to treat advanced Parkinson disease: a review. Journal of Neurosurgery, 121(3), 709-718.

López-Lozano JJ, Bravo G, Abascal J. Grafting of perfused adrenal medullary tissue into the caudate nucleus of patients with Parkinson's disease. Clinica Puerta de Hierro Neural Transplantation Group. J Neurosurg. 1991 Aug;75(2):234-43. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.2.0234. PMID: 2072160.

Marroquin LD, Hynes J, Dykens JA, Jamieson JD, Will Y. Circumventing the Crabtree effect: replacing media glucose with galactose increases susceptibility of HepG2 cells to mitochondrial toxicants. Toxicol Sci. 2007 Jun;97(2):539-47. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm052. Epub 2007 Mar 14. PMID: 17361016.

Matsumoto, K., Asano, T., Baba, T., Miyamoto, T., & Ohmoto, T. (1976). Long-term follow-up results of bilateral thalamotomy for parkinsonism. Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery, 39(3-4), 257-260.

Moldovan, A. S., Groiss, S. J., Elben, S., Südmeyer, M., Schnitzler, A., & Wojtecki, L. (2015). The treatment of Parkinson's disease with deep brain stimulation: current issues. Neural regeneration research, 10(7), 1018-1022.

Narabayashi H, Kondo T, Nagatsu T, Hayashi A, Suzuki T. DL-threo-3,4-dihydroxyphenylserine for freezing symptom in parkinsonism. Adv Neurol. 1984;40:497-502. PMID: 6421112.

Ni, L., Guan, Xl., Chen, Ff. et al. S-methyl-L-cysteine Protects against Antimycin A-induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neural Cells via Mimicking Endogenous Methionine-centered Redox Cycle. CURR MED SCI 40, 422–433 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11596-020-2196-y

NP/EFSA/PREV/2024/02 - Development of an AOP network for parkinsonian motor symptoms - https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/call/npefsaprev202402-development-aop-network-parkinsonian-motor-symptoms

Ntzani EE, Chondrogiorgi M, Ntritsos G, Evangelou E, Tzoulaki I, 2013. Literature review on epidemiological studies linking exposure to pesticides and health effects. EFSA Supporting Publication 2013; 10(10):EN-497, 159 pp. doi:10.2903/sp.efsa.2013.EN-497

Offen D, Ziv I, Sternin H, Melamed E, Hochman A. Prevention of dopamine-induced cell death by thiol antioxidants: possible implications for treatment of Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 1996 Sep;141(1):32-9. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0136. PMID: 8797665.

Parker WD Jr, Boyson SJ, Parks JK. 1989. Abnormalities of the electron transport chain in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol.26(6):719-23.

M. Peschanski, G. Defer, J. P. N'Guyen, F. Ricolfi, J. C. Monfort, P. Remy, C. Geny, Y. Samson, P. Hantraye, R. Jeny, A. Gaston, Y. Kéravel, J. D. Degos, P. Cesaro, Bilateral motor improvement and alteration of L-dopa effect in two patients with Parkinson's disease following intrastriatal transplantation of foetal ventral mesencephalon, Brain, Volume 117, Issue 3, June 1994, Pages 487–499,

Rana M, de Coo I, Diaz F, Smeets H, Moraes CT. An out-of-frame cytochrome b gene deletion from a patient with parkinsonism is associated with impaired complex III assembly and an increase in free radical production. Ann Neurol. 2000 Nov;48(5):774-81. PMID: 11079541.

Rossignol, R., Malgat, M., Mazat, J. P., & Letellier, T. (1999). Threshold effect and tissue specificity. Implication for mitochondrial cytopathies. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 274(47), 33426–33432. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.274.47.33426

Rossignol, R., Letellier, T., Malgat, M., Rocher, C., & Mazat, J. P. (2000). Tissue variation in the control of oxidative phosphorylation: implication for mitochondrial diseases. Biochemical Journal, 347(Pt 1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj3470045

Rugolo M, Zanna C, Ghelli AM. Organization of the Respiratory Supercomplexes in Cells with Defective Complex III: Structural Features and Metabolic Consequences, Life 2021 Apr 17;11(4):351. doi: 10.3390/life11040351.

Scott, R., Gregory, R., Hines, N., Carroll, C., Hyman, N., Papanasstasiou, V., ... & Aziz, T. (1998). Neuropsychological, neurological and functional outcome following pallidotomy for Parkinson's disease. A consecutive series of eight simultaneous bilateral and twelve unilateral procedures. Brain: a journal of neurology, 121(4), 659-675.

Senkevich K, Bandres-Ciga S, Gan-Or Z, Krohn L; International Parkinson's Disease Genomics Consortium (IPDGC). Lack of evidence for association of UQCRC1 with Parkinson's disease in Europeans. Neurobiol Aging. 2021 May;101:297.e1-297.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.10.030. Epub 2020 Nov 2. PMID: 33248804; PMCID: PMC8938960.

Silva MA, Mattern C, Häcker R, Tomaz C, Huston JP, Schwarting RK. 1997. Increased neostriatal dopamine activity after intraperitoneal or intranasal administration of L-DOPA: on the role of benserazide pretreatment. Synapse. 27(4):294-302.

Spencer DD, Robbins RJ, Naftolin F, Marek KL, Vollmer T, Leranth C, Roth RH, Price LH, Gjedde A, Bunney BS, et al. Unilateral transplantation of human fetal mesencephalic tissue into the caudate nucleus of patients with Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 1992 Nov 26;327(22):1541-8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199211263272201. PMID: 1435880.

Sulzer D, Surmeier DJ. 2013. Neuronal vulnerability, pathogenesis, and Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 28 (6) 715-24.

Surmeier DJ1, Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Goldberg JA. 2010. What causes the death of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson's disease? Prog Brain Res. 2010;183:59-77. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)83004

Swerdlow RH, Parks JK, Miller SW, Tuttle JB, Trimmer PA, Sheehan JP, Bennett JP Jr, Davis RE, Parker WD Jr (1996) Origin and functional consequences of the complex I defect in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 40(4):663-71.

Swiss R, Will Y. Assessment of mitochondrial toxicity in HepG2 cells cultured in high-glucose- or galactose-containing media. Current Protocols in Toxicology. 2011 Aug;Chapter 2:Unit2.20. DOI: 10.1002/0471140856.tx0220s49. PMID: 21818751.

Szibor, M., Gainutdinov, T., Fernandez-Vizarra, E., Dufour, E., Gizatullina, Z., Debska-Vielhaber, G., … & Moore, A. L. (2020). Bioenergetic consequences from xenotopic expression of a tunicate AOX in mouse mitochondria: switch from RET and ROS to FET. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics, 1861(1), 148137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbabio.2020.148137

Uitti, R. J., et al. "Amantadine treatment is an independent predictor of improved survival in Parkinson's disease." Neurology 46.6 (1996): 1551-1556.

Tebby C, Gao W, Delp J, Carta G, van der Stel W, Leist M, Jennings P, van de Water B, Bois FY. A quantitative AOP of mitochondrial toxicity based on data from three cell lines. Toxicol In Vitro. 2022 Jun;81:105345. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2022.105345. Epub 2022 Mar 10. PMID: 35278637.

Uitti, R. J., Wharen Jr, R. E., Turk, M. F., Lucas, J. A., Finton, M. J., Graff-Radford, N. R., ... & Atkinson, E. J. (1997). Unilateral pallidotomy for Parkinson's disease: comparison of outcome in younger versus elderly patients. Neurology, 49(4), 1072-1077.

van der Stel W, Carta G, Eakins J, Darici S, Delp J, Forsby A, Bennekou SH, Gardner I, Leist M, Danen EHJ, Walker P, van de Water B, Jennings P. Correction to: Multiparametric assessment of mitochondrial respiratory inhibition in HepG2 and RPTEC/TERT1 cells using a panel of mitochondrial targeting agrochemicals. Arch Toxicol. 2020 Aug;94(8):2731-2732. doi: 10.1007/s00204-020-02849-5. Erratum for: Arch Toxicol. 2020 Aug;94(8):2707-2729. doi: 10.1007/s00204-020-02792-5. PMID: 32720191; PMCID: PMC7645484.

Van der Stel W, Carta G, Eakins J, Delp J, Suciu I, Forsby A, Cediel-Ulloa A, Attoff K, Troger F, Kamp H, Gardner I, Zdrazil B, Moné MJ, Ecker GF, Pastor M, Gómez-Tamayo JC, White A, Danen EHJ, Leist M, Walker P, Jennings P, Hougaard Bennekou S, Van de Water B. New approach methods (NAMs) supporting read-across: Two neurotoxicity AOP-based IATA case studies. ALTEX. 2021;38(4):615-635. doi: 10.14573/altex.2103051. Epub 2021 Jun 10. PMID: 34114044.

van der Stel W, Yang H, Vrijenhoek NG, Schimming JP, Callegaro G, Carta G, Darici S, Delp J, Forsby A, White A, le Dévédec S, Leist M, Jennings P, Beltman JB, van de Water B, Danen EHJ. Mapping the cellular response to electron transport chain inhibitors reveals selective signaling networks triggered by mitochondrial perturbation. Arch Toxicol. 2022 Jan;96(1):259-285. doi: 10.1007/s00204-021-03160-7. Epub 2021 Oct 13. PMID: 34642769; PMCID: PMC8748354.

Walter, Benjamin L., and Jerrold L. Vitek. "Surgical treatment for Parkinson's disease." The Lancet Neurology 3.12 (2004): 719-728.

Wang S, Zheng X, Ou R, Wei Q, Lin J, Yang T, Xiao Y, Jiang Q, Li C, Shang H. Rare variant analysis of UQCRC1 in Chinese patients with early-onset Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2024 Feb;134:40-42. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2023.09.004. Epub 2023 Sep 20. PMID: 37984314.

Widner H, Tetrud J, Rehncrona S, Snow B, Brundin P, Gustavii B, Björklund A, Lindvall O, Langston JW. Bilateral fetal mesencephalic grafting in two patients with parkinsonism induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP). N Engl J Med. 1992 Nov 26;327(22):1556-63. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199211263272203. PMID: 1435882.

Zhao YW, Pan HX, Wang CY, Zeng Q, Wang Y, Fang ZH, Huang J, Li X, Wang X, Zhang X, Liu ZH, Sun QY, Xu Q, Lei LF, Yan XX, Shen L, Jiang H, Tan JQ, Li JC, Tang BS, Zhang HN, Guo JF. UQCRC1 variants in Parkinson's disease: a large cohort study in Chinese mainland population. Brain. 2021 Jul 28;144(6):e54. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab137. Erratum in: Brain. 2021 Oct 22;144(9):e78. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab228. PMID: 33779694.

Zhou C, Huang Y, Przedborski S. Oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease: a mechanism of pathogenic and therapeutic significance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008 Dec;1147:93-104. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.023. PMID: 19076434; PMCID: PMC2745097.

Search strings

Each strategy followed this structure: Stressor AND Parkinson

Parkinson’s Disease

|

PubMed |

("Parkinsonian Disorders"[MeSH Terms:noexp] OR "Parkinson Disease"[MeSH Terms] OR "Lewy Body Disease"[MeSH Terms] OR "lewy bodies/pathology"[MeSH Terms] OR "Synucleinopathies"[MeSH Terms:noexp] OR "Tremor"[MeSH Terms]) OR (Parkinson* [Title/Abstract] OR paralys*-agitans[Title/Abstract] OR Shaking-pals*[Title/Abstract] OR Synuclein*-Patholog*[Title/Abstract] OR synucleinopathol*[Title/Abstract] OR synuclein*-linked-disease*[Title/Abstract] OR synuclein*-linked-neurodegenerat*[Title/Abstract] OR synuclein*-linked-neuro-degenerat*[Title/Abstract] OR synuclein-linked*-oligodendrogliopath*[Title/Abstract] OR TREMOR*[Title/Abstract] OR QUIVER*[TITLE/ABSTRACT] OR ((LEWY*[tiab]) AND (DEMENT*[Title/Abstract] OR DISEASE*[Title/Abstract] OR PATHOL*[TIAB] OR DISORDER*[tiab]))) |

|

EMBASE |

('parkinsonism'/exp OR 'Parkinson disease'/de OR 'synucleinopathy'/de OR 'tremor'/exp OR 'diffuse Lewy body disease'/exp OR 'Lewy body'/exp) OR (Parkinson*:ti,ab,kw OR paralys*-agitans:ti,ab,kw OR Shaking-pals*:ti,ab,kw OR Synuclein*-Patholog*:ti,ab,kw OR synucleinopathol*:ti,ab,kw OR synuclein*-linked-disease*:ti,ab,kw OR synuclein*-linked-neurodegenerat*:ti,ab,kw OR synuclein*-linked-neuro-degenerat*:ti,ab,kw OR synuclein-linked*-oligodendrogliopath*:ti,ab,kw OR TREMOR*:ti,ab,kw OR QUIVER*:ti,ab,kw OR ((LEWY*:ti,ab,kw) AND (DEMENT*:ti,ab,kw OR DISEASE*:ti,ab,kw OR PATHOL*:ti,ab,kw OR DISORDER*:ti,ab,kw))) |

|

Scopus |

( ( ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( lewy* AND ( dement* OR disease* OR pathol* OR disorder* ) ) ) OR ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( parkinson* OR paralys*-agitans OR shaking-pals* OR synuclein*-patholog* OR synucleinopathol* OR synuclein*-linked-disease* OR synuclein*-linked-neurodegenerat* OR synuclein*-linked-neuro-degenerat* OR synuclein-linked*-oligodendrogliopath* OR tremor* OR quiver* ) ) ) ) |

|

Web of Science |

TS=((Parkinson* OR paralys*-agitans OR Shaking-pals* OR Synuclein*-Patholog* OR synucleinopathol* OR synuclein*-linked-disease* OR synuclein*-linked-neurodegenerat* OR synuclein*-linked-neuro-degenerat* OR synuclein-linked*-oligodendrogliopath* OR TREMOR* OR QUIVER*) OR (LEWY* AND (DEMENT* OR DISEASE* OR PATHOL* OR DISORDER*)) and Preprint Citation Index (Exclude – Database)) |

Stressors

|

Antimycin |

|

|

PubMed |

("Antimycin A"[Mesh] OR AntimyciN*[TIAB]) |

|

EMBASE |

('antimycin A1'/exp OR AntimyciN*:ti,ab,kw) |

|

Scopus |

( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( Antimycin-A OR Antimycin* ) ) |

|

Web of Science |

TS=(Antimycin-A OR Antimycin*) |

|

Picoxystrobin |

|

|

PubMed |

((Picoxystrobin*[Title/Abstract]) OR ("picoxystrobin" [Supplementary Concept])) |

|

EMBASE |

(picoxystrobin*:ti,ab,kw OR 'picoxystrobin'/exp) |

|

Scopus |

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( picoxystrobin* ) |

|

Web of Science |

PICOXYSTROBIN* |

|

Pyrachlostrobin |

|

|

PubMed |

("pyrachlostrobin"[Supplementary Concept] OR "F-500"[Title/Abstract] OR "pyrachlostrobin*"[Title/Abstract] OR PYRACLOSTROBIN*[TIAB] OR PIRACLOSTROBIN*[TIAB] OR PIRACHLOSTROBIN*[TIAB]) |

|

EMBASE |

('pyrachlostrobin':ti,ab,kw OR 'f 500':ti,ab,kw OR 'bas 500f':ti,ab,kw OR pyrachlostrobin*:ti,ab,kw OR pyraclostrobin*:ti,ab,kw OR piraclostrobin*:ti,ab,kw OR pirachlostrobin*:ti,ab,kw OR 'pyrachlostrobin'/exp) |

|

Scopus |

( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( pyrachlostrobin* OR pirachlostrobin* OR PYRACLOSTROBIN* OR PiRACLOSTROBIN* OR f-500 OR "bas 500f" ) ) |

|

Web of Science |

(TS=(pyrachlostrobin* OR pirachlostrobin* OR PYRACLOSTROBIN* OR PiRACLOSTROBIN* OR f-500 OR "bas 500f") |